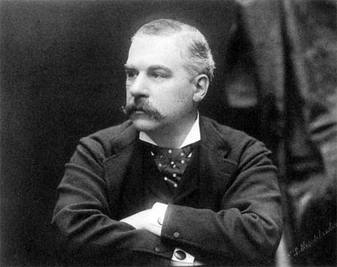

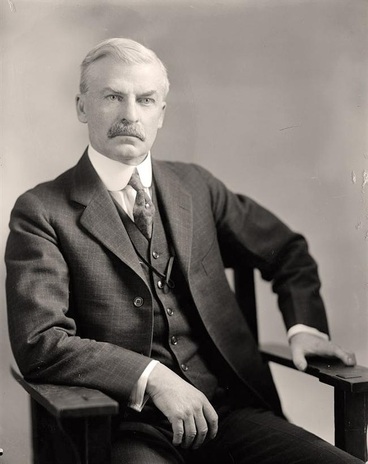

Joseph Kinsey Howard was born in Iowa on February 28, 1906. His family moved to Lethbridge in Alberta, Canada, when he was young. His father abandoned the family when Joe was 12-years-old.

Joe’s mother was the lady’s page editor of the Lethbridge Herald at the time. Her husband now gone, she moved the family to Great Falls that same year, 1919. It’s speculated that she moved herself and Joe down to Montana because she knew she’d get a better education for him there.

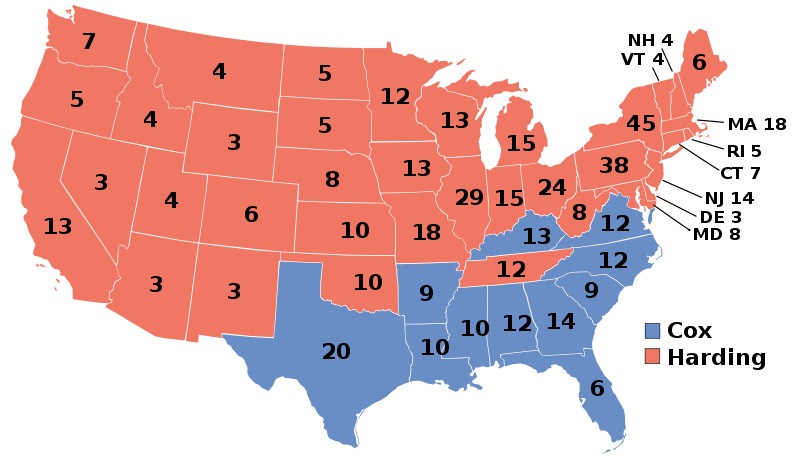

It’s wasn’t a good time to come to Montana. The economy was in tatters.

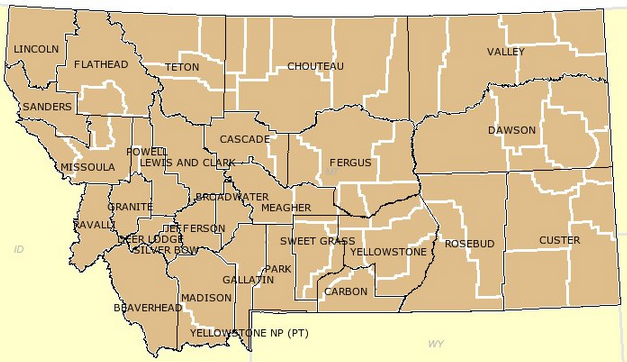

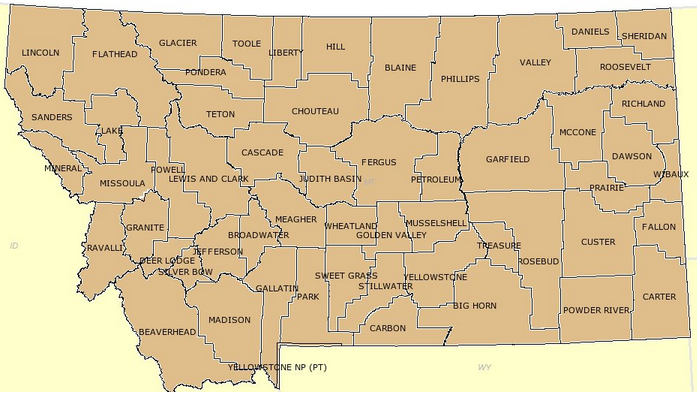

The economic depression was hard in Montana, with 2 million acres going out of farm production and 11,000 farms abandoned, 20% of all in the state.

By 1919 there were 3,000 destitute farmers in Hill County, all without a penny in their pocket and an ounce of hope in their souls. They’d been beaten, and badly. Montana had had its way with them, and they knew it.

The 1919 drought meant the state lost $50 million in revenue due to crop losses. When wildfires kicked up that spring and into the summer it cost another $20 million, this time in damages. Cattlemen couldn’t find enough grass or hay for their animals and had to have it shipped in, something that caused speculation in the market and drove prices of shoddy grasses up to $50 a ton by winter.

By 1920 the farming practices that’d furrowed deeply into the soil came back to haunt the homesteaders. Winds kicked up and lasted for days at a time, blowing so strong that “dusters” developed, an early taste of what the American Dust Bowl would be like during the next decade. Joe tells how it “drifted against the doorway like snow.”

Montana had sent 40,000 men off to World War I, chiefly because of a clerical error made by the state adjutant general that listed Montana’s population as 952,478 instead of 496,131 like it should have been. Montana therefore sent 25% more men than any other state in the union, based on population.

Of those men, 943 of them died of wounds or disease while overseas and 2,437 were wounded in the conflict. All the men wanted to do was get back home, but they had nothing to come back to – the farms were failing, the mines were closing, and the lumber yards were laying off men. They left the state, already wounded in many ways from the war, even if sight unseen. It was devastating to a ounce-young state. Howard puts it well:

“Within a few years Montana was transformed from a young people’s state to a state of young children and old men and women. The injury to the economic organism was permanent: nothing could ever reestablish population balance save a catastrophe which would wipe out the entire citizenry and leave a clean slate for a new start. Grave pension and relief problems could be anticipated: more and more unemployed and aged Montanans to be supported by fewer and fewer young workers.”

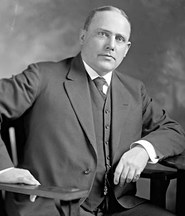

Joe graduated from Great Falls High School in 1923 and became a reporter for the Great Falls Leader. He was just 17-years-old. The paper had started in 1888 and competed with the rival Great Falls Tribune before stopping the presses for good in 1969.

Howard was made news editor in 1926, when he was just 20-years-old. During his more than twenty-year tenure at the paper he profiled Native American issues, the growing corporate corruption in the state, as well as national interest pieces for The Nation, Harper’s Magazine, Time, and Life. He also dabbled in short stories, which were run in The New York Times, The Saturday Evening Post, and Esquire.

Meanwhile, life in Montana was hard.

The state’s farmers were forced to become more businesslike in their operations, and this caused their politics to shift as well. Howard attribute’s “much of the state’s reversion to political conservatism after eras of stormy agrarian movements” to this fundamental shift – from producing with your hands to producing by machine.

That transition took a fair amount of the farmer’s freedom, and he’s never been able to get it back. Indeed, it was also the sounding of his death knell. In 1910 there were 6.3 million farms in America with 32 million people living on them. By 2010, however, there were just 2.2 million farms and 6.1 million people working on them.

All of this mechanization and increase in costs led to a trend called “sidewalk farming,” where someone operates their farm from town or moves to town over winter. The trend of people working on farms but not living on them began. Mechanization on the farms and better roads for the car were all reasons for this, Howard tells us, and he explains the effect of this well:

“’Sidewalk farming,’ once started, grows like a snowball. Families which choose at first to remain on their farms find themselves isolated as their neighbors move; next year they move too. Social and cultural community are lost. The farm becomes merely an economic apparatus like a factory; its owner, in town, joins a luncheon club and the Chamber of Commerce and is persuaded that his interests coincide with those of other substantial businessmen.”

By the 1920s the range was in total disrepair, with sketchy ownership claims and far too many animals. Howard tells us that “4,000 cattle, 2,000 horses, and millions of prairie dogs” called the place home.

Joe was presciently right. Montana would be the only state to lose population during the 1920s and what happened there during that time would set the stage for much of the rest of the nation in the decade to follow. Howard wrote his words in 1943 and yet more than seventy years later the state is still facing a demographic crisis that creates an unsustainable economic model, one where young people only take care of the old and little if anything is produced.

That was the Montana Joe grew up in.