Joseph M. Dixon

Joseph M. Dixon

Following the disastrous 1912 election in Montana, Joseph M. Dixon headed back to his law practice and his newspaper in Missoula, and also took on a dairy farm to take care of that pesky free time. In 1917 he had sold the Missoulian newspaper, although who he sold it to is a bit unclear. One wants to believe that he wouldn’t have sold it to his nemesis the Anaconda Company, but that’s exactly who was holding the Seattle bank notes representing majority ownership, at least according to the wife of 1920s Missoulian editor Martin K. Hutchens. (Stearns, 10)

By 1920, however, he was back with a fury. He began to alarm people while running in 1920 when he called for an income tax as well as more “long and short haul” legislation for railroads. He wanted a direct primary, something else that rankled the political elites. And he wanted to finally tax the mining companies what they should rightly be taxed at. As K. Ross Toole writes of the time:

Wherever the Company looked in the years between 1918 and 1920 there were dark and ominous clouds on the political horizon. There was Wheeler and there was Dixon. There was also a spellbinding young Republican, Wellington D. Rankin, and his sister, Jeanette, who, with strong Non-Partisan League support, had become the first woman elected to Congress in 1916. And there was Sam C. Ford, restive as a Republican attorney general, angry with red-baiting politicians and at odds with the Company. (Toole, Twentieth-Century Montana p 235)

Wheeler was of course none of those things. He’d arrived in Butte in 1905, been elected to the Montana House in 1910, and then became U.S. District Attorney in for Montana in 1913. Wheeler headed back to private practice in Butte when his term ended in 1918 and then tried for governor in 1920.

During the campaign Dixon worked to heal rifts created by his jump to the Bull Moose Party in 1912, which was still rankling some Republicans eight years later. With the company newspapers behind him it was easy for Dixon to beat out Wheeler in a landslide to become the seventh governor of Montana, winning by a huge 37,000-vote margin, 111,113 to 74,874, or 59% to 40%.

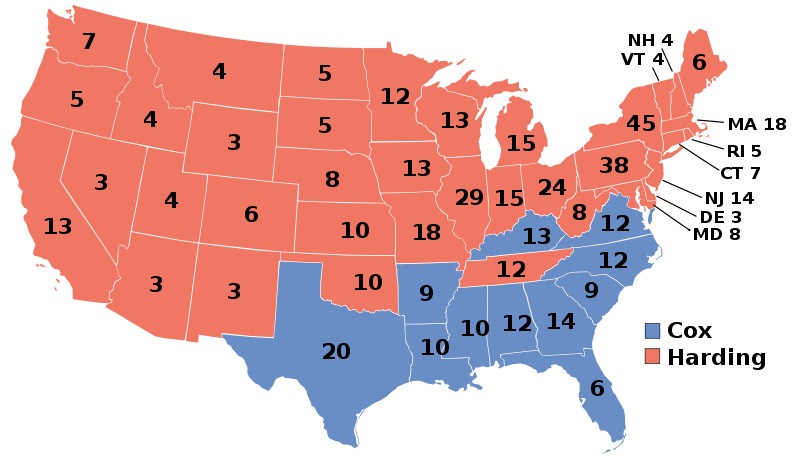

Dixon had even taken more votes than Warren G. Harding had in the presidential race. Republicans were the big winners all around that year, with Warren G. Harding sweeping into the White House over Democrat James M. Cox, 16 million votes to 9 million, or 60.3% to 34.2%.

It was clear the idea of taxing mines – like Levine had espoused back in Lewistown two years earlier and governors had done decades before – was an answer to the problem. But would there be the political will, especially with Anaconda controlling the newspapers? Governor Dixon intended to find out, and he gave one of the most memorable addresses to any legislature.

Montana had sent 40,000 men to WWI, Dixon told the legislature, and made it clear that the same amount of young men that’d left the state for war weren’t coming back, and not just because of deaths. He pointed out that there were no taxable assets the state could make money from, since farmers were going broke and taxes on corporations were so low. He called for more taxes – an income tax, inheritance tax, and licensing tax on public service corporations – so that the state could once again go about filling its coffers just so it could operate as a going concern.

Seeing the way mining and resource exploitation was going in the state, Dixon called for a 3% gross tax on oil, a 1% tax on gasoline, and an increased tax on vehicle licenses for the 60,000 automobiles that were then driving around the state. He wanted to double Workmen’s Compensation benefits, to the staggering amount of $100 and four weeks of medical care. He also called for the creation of a tax commission with members appointed for six-year terms.

Dixon pointed out the problem well, stating that the Northern Pacific Railroad paid taxes on just $682 in net profits when their gross profits had been $7.7 million. It would have been comical how absurd it all was if common people weren’t suffering because of policies put in place decades before to benefit the rich industrialists.

He called for reapportionment and redistricting and the legislature sat there and listened to it all and didn’t know what to make of it. Many probably thought him drunk on illegal liquor, others that he’d perhaps taken a hit on the head before speaking. None could believe what they were hearing.

Unfortunately clarity wasn’t what Anaconda Copper was looking for – they were looking for profits. Dixon’s single term as governor was hamstrung by Anaconda Copper Mining Company and any legislation he tried to get passed was shot down in the company-owned newspapers before it even had a chance. While it’s true that Dixon had owned the Missoulian, that meant nothing, and he could in no way stand up to the twelve other newspapers across the state in the 1920s, which together had a further reach and significantly-higher readership.

The Company immediately set its newspapers and lobbyists to smash Dixon’s agenda. K. Ross Toole gives a good account of what this entailed in the Capitol:

Although the approaches and devices of lobbying were varied, imaginative, and myriad, one of the standard methods employed (which was rendered enormously effective because of the Company’s almost total control of the press) was to introduce extraneous bills and then devise interminable debate and extensive press coverage of the same. This served three purposes: it confused the inexperienced legislator as to the proper priority of things; it enabled the press to attack or laud specific legislators (or the governor) on matters unrelated to anything that really mattered; it hoodwinked the public and covered the legislative scene with a cloud of obfuscatory verbiage. (Toole, Twentieth-Century Montana p 260-1)

He knew the only way to get that under control was with taxes, and he knew the only way to stop the shifting population in the state was through economic security. Few, however, wanted to listen.