Mike Fink

Mike Fink So much of what is known about Mike Fink today may just be tall tales. A large amount of Mike Fink literature appeared as early as the 1820s and continued into the Jacksonian era. Editors found that a story with Mike Fink in it would sell, and they used his name however it suited them, especially when they could embellish the ‘facts’ that were known.

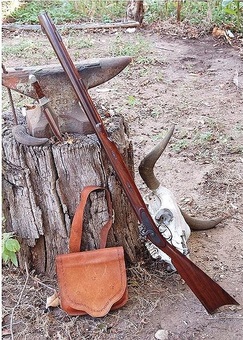

A Gifted Shot

Great Miami River

Great Miami River During his teen years he regularly worked as an Indian scout, and his marksmen skills were notable. After all, he grew up among the militiamen of the fort, and no doubt spent hours watching them practice with their rifles before he was allowed to begin using one himself. At one point his shooting became so good that he wasn’t allowed to participate in the marksmanship competitions any longer, since he “spoilt” all the fun.

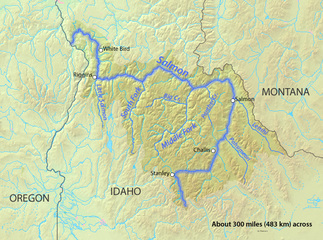

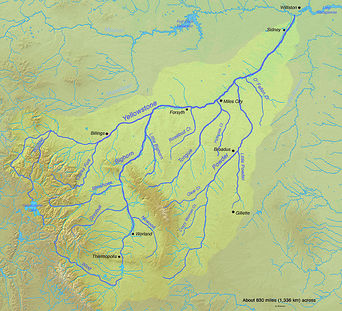

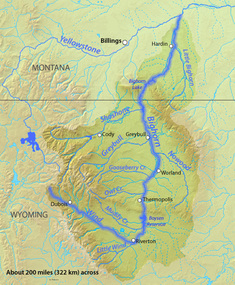

The Indian wars around the area concluded in the 1790s, but Fink wasn’t ready to settle down to a life of farming like many of his scouting companions. He drifted west, coming into the transport business on either the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, or the Great Miami River which led from the Ohio River to Fort Laramie. From there he’d head up the Maumee River to Lake Erie. He stayed a part of the trade for more than twenty years, and even became a captain of the boats he served on. The life suited him until 1815 when he decided to move further west.

A Practical Joker

Mississippi River and its tributaries

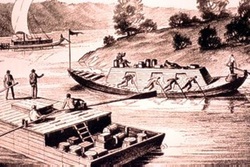

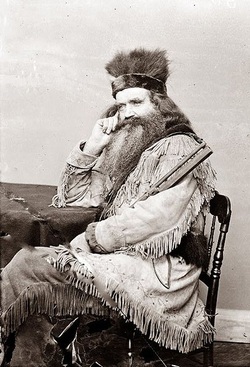

Mississippi River and its tributaries He also prided himself on his humor. His knack for practical jokes was well-known, as was his anger at anyone who found them a trifle unfunny. And he could back up his words with actions, for pushing a keelboat upriver day-after-day made anyone’s body hard and lean, but Fink’s more than most it seemed. He was just under six feet tall and weighed in at 180 pounds, most of it muscle.

Like most mountain men, Fink liked to drink. He claimed he could finish off a gallon of whiskey and still shoot straight. One newspaper writer had him drinking at least a gallon and possibly more of “flem-cutter” or “anti-fogmatic” and then declaring that “he must fight something…or catch the dry rot.” He was well-known for his ability to finish off a gallon in 24 hours, showing little effect for his efforts.

He may not have been boasting. For fun, he and his friends enjoyed using cups of whiskey for target practice, cups which they placed on one another’s heads and shot at anywhere from thirty to seventy yards away. He was thought to have shot a lock of hair off of an Indian from some distance, and even the deformed heel off the foot of an African-American slave.

That last got him brought up on charges, probably by the man’s owner. Fink claimed to the circuit court judge in the case that he was only allowing the man to wear a proper shoe. The judge didn’t agree and found Fink guilty, although the sentence must have been light, as he was soon back on the river. As compensation, Fink sent the man “a handful of silver…to extract the pain from his shortened heel.”

Another tale has him about to appear in court, and it may well have been the same case. Instead of going on foot like most reasonable men, Fink ordered his men to put his boat on a wagon and haul it through town to the court, explaining that he “felt at home nowhere but in his boat and among his men.”

Yet another had him finding a dinner of mutton for his men. Seeing a group of good-looking sheep, he stuffed “Scotch snuff” up the poor animals’ noses. When they were wheezing and sneezing enough, Fink reported to the farmer who owned the hapless animals that they’d all come down with “black murrain.” The farmer was so glad to get rid of the animals that he gave them to Fink and his men, as well as a “couple of gallons of old Peach brandy” for all the help they’d given him.

Whether the tales were true or not is unclear, but the reputation they granted Mike Fink was certain. He was known as a boastful and tempestuous man, but a lighthearted one as well. Most knew him as one best not to cross.

Fink was also quite chivalrous. He liked to travel with a woman named Pittsburgh Blue, but he allowed no one else to talk to her. When he was feeling in a particularly boastful mood, he’d instruct her to walk a goodly distance away, place a tin cup full of whiskey on her head or between her knees, which he would then put a bullet clean through.

Joining Up

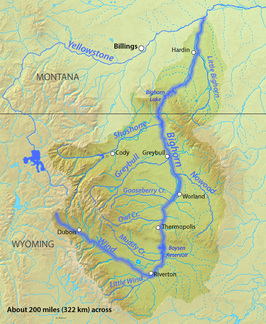

Two others that joined that day were named Levi Talbot and Bill Carpenter. Whether Fink had travelled with them along the Ohio and Missouri Rivers, or met them for the first time that fall in St. Louis, they would become Fink’s closest friends. Mike worked hard on the river, trapping and hunting and helping the trade flourish, until his boastful and tempestuous nature finally got the better of him.

A Final Cup

Thomas Bangs Thorpe sketch, 1854

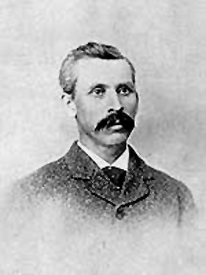

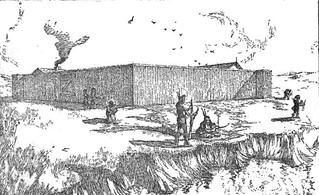

Thomas Bangs Thorpe sketch, 1854 When they returned to the fort, however, the argument started up again, no doubt helped by liberal amounts of whiskey. They probably drank more, and as so often happens, made up. To seal the deal, they agreed to shoot cups of whiskey from one another’s heads. After a coin toss it was determined that Carpenter would go first. Sensing that this day might be his last, he handed Talbot his gun and other possessions, then paced out sixty or seventy yards and put the cup of whiskey upon his head. But instead of putting a bullet clean through the cup, Fink put it clean through Carpenter’s forehead. Whether Fink missed on accident or on purpose can’t be known, although he’s reported to have said that it was “all a mistake,” while cursing his gun.

There were no lawmen in those parts, and Fink’s miss was accepted as an accident by his companions. All, that is, but for Talbot. Accounts differ as to whether it was immediately after the shooting of Carpenter, or several months later, but the gist remains the same. While boasting once again of his past feats, Fink let slip that he was happy he had killed Carpenter. Talbot immediately rose, drew the pistol that Carpenter had given to him on that fateful day, and shot Fink dead.

And just like Fink, Talbot didn’t have to pay for his crime, although he wouldn’t live much longer anyway. Later that August he was fighting under Colonel Leavenworth during the Arikara War, and earned great distinction. He didn’t have much time to savor his newfound fame, however, for just ten days later he fell into the Teton River and drowned.

The trio of men that had joined Ashley’s Hundred together were now dead, a fate that would befall many from that illustrious group. And the Missouri River and its tributaries were now a quieter place as well, for with Talbot’s revenge, Mike Fink was silenced at last. He was 43 years old.

Allen, Michael. Western Rivermen, 1763-1861: Ohio and Mississippi Boatmen and the Myth of the Alligator House. Louisiana State University Press: Baton Rouge, 1990. p 9-13.

Chittenden, Hiram Martin. The American Fur Trade of the Far West [Vol 2]. University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1986. p 697-702.

Van Ravenswaay, Charles. Saint Louis: An Informal History of the City and its People, 1764-1865. Missouri Historical Society Press: Columbia, 1991. p 164-5.

Vestal, Stanley. Jim Bridger: Mountain Man. Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1946. p 25-6.

Brown, Mark H. The Plainsmen of the Yellowstone: A History of the Yellowstone Basin. Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1969. p 65-6.