MT and Qing flags

MT and Qing flags

In the mid- to late-19th-century, for instance, thousands of Chinese came to the Montana Territory.

Work was the biggest draw, and when many were through with their employment they left. Many stayed, however, and in this post we’ll tell their stories.

The Chinese Come to Montana

Many Chinese families had been disrupted by the Opium Wars of 1839-42 and 1856-60. Foreign powers came in and dominated a once-proud nation.

Another factor making life difficult was the Taiping Rebellion of 1851 and the 25 years of drought and famine that stretched into 1873. Both of those events caused the deaths of 60 million Chinese.

It’s no wonder that many sought out better opportunities, going from the rural, inland areas to the coastal cities. From there they boarded ships for America.

By 1854 California had more than 40,000 Chinese. Between 1850 and 1900 about 5 million people left China, most from those southern coastal areas. Of these, about 500,000 came to America.

Wiley Davis, in his essay called “Chinese in Virginia City, Montana” tells us that there were Chinese in Bannack in 1863 for there “was one or two Chinamen that left Bannack” that year, “headed for Alder Gulch.”

The Montana Post tells us of six Chinese arriving in Montana on June 3, 1865. It was the first mention of Chinese people in Montana.

These men were Ho-Fie, So-Sli, Lo-Flung, Ku-Long, Whang and Hong.

The Montana Gold Mining and Fluming Company was the main importer of Chinese into Montana. They did this because the Chinese worked hard for low wages.

The Montana Post was out of business by 1866 but the Chinese were still coming. By 1869 three businesses were owned by Chinese.

On January 24, 1866, an advertisement ran in a Helena newspaper telling the Chinese that they must:

“suspend the washing, or laundry business, immediately or they will be visited by a Committee of Ladies who have determined that they will not see the bread taken from the mouths of themselves and children by these celestial heathens and they will remain idle for want of employment.”

The letter was signed by “A Committee of Ladies.”

Mining was the big draw for the Chinese, and there were plenty of other places besides Helena.

For instance, we know that the “first caravan of Chinese came to Alder Gulch in 1867,” according to a 1976 Madison County History Association report. Lucille Dixon wrote the short article called “Chinese in Alder Gulch.”

In an essay called “Law and Chinese in Frontier Montana,” Texas historian John R. Wunder gives us a good look at the Chinese in the earliest times.

Mainly they came from “California, Colorado, Nevada, and other mining areas in the West, as well as from China.” The reason they came all the way across the ocean was:

“They had the reputation of working harder than whites and for lower wages, of working old mine tailings with success, and of working closely together to maximize their efforts.”

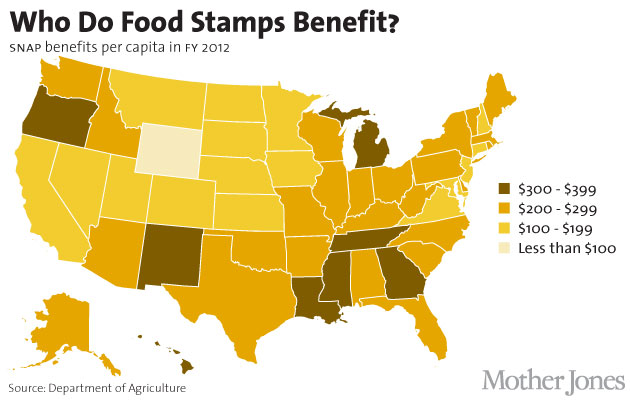

In 1870 the Chinese made up 10% of Montana’s population. Also that year, 25% of all miners in the American West were Chinese, though just a third of the Chinese population in the country was employed in that trade.

In 1870 there were 660 Chinese living in or around Helena. We know there were 452 Chinamen working the placer claims of Lewis and Clark County in that year.

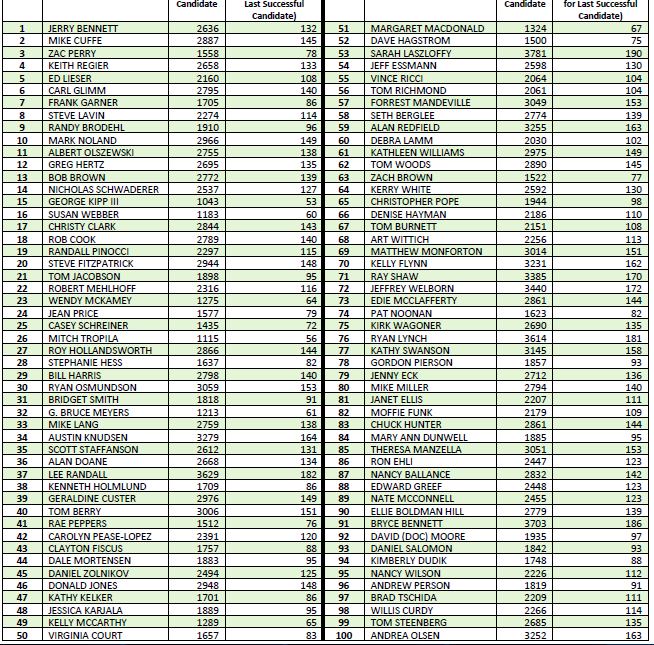

What’s more, we know that Chinese employment in Lewis and Clark County broke down like so:

- 452 were placer miners, or 75%

- 56 were washermen, or 10%

- 31 were cooks or domestic servants, or 5%

- 7 were gamblers

- 6 were clerks

- 6 were grocers

- 5 were saloon workers

- 4 were bakers

- 2 were waiters

- 3 were doctors

- 1 was a restaurant owner

- 1 was a tailor

- 1 was a boarding house proprietor

Of these men, 56% were married and 44% were single. Their average age was 35-years old.

We know that in 1880 there were 19 Chinese women in Lewis and Clark County. All but two were listed as prostitutes, with another listed as wife. Their average age was 27-years old.

It was that 1880 census that told us the number of Chinese in Montana had slipped from 10% of the population to 5%. In 1890 it fell 1.9%.

Those numbers might seem small, but nationally Chinese made up just 0.2% of the country’s population during those decades.

A large reason for this decline was the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 that prohibited Chinese laborers from entering America for ten years.

When Congress passed the Scott Act in 1888 (something that strengthened the Chinese Exclusion Act), there were 20,000 Chinese laborers visiting China that weren’t able to return to America.

By 1902 all Chinese were banned from entering the country.

From 1882 to 1945 an average of 215 Chinese women were allowed into America each year. “Between 1924 and 1930, no Chinese wives legally entered the United States.”

The Alder Gulch “China War” of 1880

The newspaper was based out of Virginia City and located on Wallace Street. It could also have been Wallace, Idaho. Either way, it went on to say that:

“By the turn of the century, with the dredges working the placer ground below Virginia City and diggings becoming scarce, the population began to dwindle quickly with many of them moving to Butte, Helena, Dillon or Bozeman to go into business.”

It was reported in October 1878 that “lots of Chinese had left for Butte.” The main reason for this was the drying up gold mining industry, at least for individuals. At the time, however, Butte wasn’t the friendliest place for Chinese.

In 1872 the territorial legislature had passed a law “charging fees to Chinese-owned laundries” and in 1883 it was “effectively illegal for Chinese to own mining claims in Montana.”

In her report, Dixon went on to mention the “China War” that raged in Alder Gulch in 1880 between the companies of Hi Chung and Sam Wah.

“It happened near the mouth of Water Gulch,” Dixon tells us, and it seems they were fighting over an area “just vacated by the Hop Lee Company.” We’re told that all the businesses in Virginia City and Alder Gulch had to go without meals or prepare their own because all the Chinese workers were gone, taking one side or another in the conflict.

In 1881 the “tong war broke out,” though whites were only affected by an increase in arrests for vandalism.

“This war actually didn’t amount to much although two were killed and there were numerous injuries from being banged about with a shovel. It ended with 11 in jail on charges of murder.”

The Montana News Association told us in June 1941 about the Chinese war in Alder Gulch in 1880. There were six Chinese companies at the time.

“Whether the companies were connected with the six great Chinese tongs in control of the Chinese colony in San Francisco is not known but the impression prevailed in Virginia City that the connection was fleeing down the gulch, closely pursued by a tall Chinese, armed with a sharpened shovel.”

The Madisonian was reporting that by 1907 there were no more Chinese in the city. By the 1920s the Chinatown there had been torn down to make way for the highway.

One Census list at the Montana Historical Society gives the following numbers for Chinese in Montana:

- 1870: 1,949

- 1880: 1,765

- 1890: 2,532

- 1900: 1,739

- 1910: 1,285

- 1920: 872

- 1930: 486

- 1940: 258

- 1950: 209

For Japanese in Montana, the numbers look like this:

- 1890: 6

- 1900: 2,441

- 1910: 1,585

- 1920: 1,074

- 1930: 753

- 1940: 508

- 1950: 524

The Eighth Report of the Bureau of Agriculture, Labor and Industry of the State of Montana came out in November 1902 and gave us some good numbers on minority populations in Montana.

For instance, in 1880 “there was not a Jap in Montana.” The report goes on to say that “ten years later there were six” and by 1900 that’d increased to 2,441. Chouteau County had the most Japanese, with 628 followed by Missoula County at 398.

In 1900 there were 1,739 Chinese in Montana, thirty-nine of whom were women.

Discrimination Against the Montana Chinese

In a letter to the editor of the Helena Daily Herald on July 7, 1870, we see what common citizens often thought of the Montana Chinese:

“living don’t cost them anything, if garden patches and chicken roost are anywhere in the neighborhood, for cleptomania [sic] is a chronic disease among all Chinamen.”

The letter goes on to say that:

“The Union party can make citizens and soldiers out of them, and Tammany Hall can manufacture Democrats out of them and in that manner they will become identified with us…”

“What early good, therefore, can there be in welcoming to our land a race of beings whose habits and customs are diametrically opposed to ours.”

The Anaconda Standard reported in January 1894 in an article called “Chinese are Registering” that the:

“Chinese residents of Livingston are all preparing to register under the provisions of the Geary act of Nov. 25, 1893. There are 37 almond-eyed Celestials in this city and about half of these have already had their photographs taken and the others are rapidly following suit. Deputy Internal Revenue Collector E. Butler of Miles City will arrive in Livingston in a few days and open a Chinese registrar’s office.”

“John Conley came in from Deer Lodge yesterday to round up the Chinese in his neighborhood,” the Anaconda Standard reported on January 12, 1894.

Conley was the special revenue agent “in charge of the Chinese branch of the service.”

“The celestials do not appear to like having their photographs taken and endeavor to disguise themselves as much as possible by wearing soft hats, which they pull down over their eyes, and on this account many photographs have been rejected.

Each Chinaman has to provide the government with two photographs one of which is filed in Helena with the revenue collector and the other sent to the treasury authorities at Washington.”

Mixed Marriages with Chinese

On February 23, 1908, the Butte Miner had a headline reading “St. Louis girl weds Deer Lodge Chinese.” The article says how William Troy, “a Chinaman, born in San Francisco, and educated in New York City,” married Miss Alice Waddell at a restaurant owned by Rev. George O. Jewett.

A similar report ran in the Helena Daily Independent on February 2, 1909, called “White woman weds Chinaman.” It profiled how Margaret Gillett, “a white woman, of English descent,” was married to Yee Hoe Joe by Terrence O’Donnell in the “basement of the county court house.”

The article goes on to say that “the oriental says he has lived in Helena for ‘longee time’ and has been engaged as a cook for the family of George Tracy.” Gillett came to Helena twelve months before from St. Paul and seems to have been employed as a maid or domestic servant.

Early Chinese Businessmen in Montana

Chin Hin Doon was a Chinese man that came to Montana. He’d been born in southeast China in 1856 and came to America in 1875. By 1894 he was in Butte where he became a partner in the Wah Chong Tai Company, a mercantile business.

Chin came from Guangzhou Province and the city of Canton, or today’s Guangzhou/Shenzhen. He, like many Chinese families, had been disrupted by the Opium Wars and the Taiping Rebellion.

We’re told by historian Richard I. Gibson that Chin had special privileges as a merchant, which allowed him to send for his son in the 1880s, well after the bans on Chinese entering the US were in effect.

We know that in 1910 Chin was the leading investor in the Wah Chong Tai Company, with $5,000 put in. The next highest investor was Chin’s son, Chin Yee Fong, who put in $2,000.

The company had been created in 1868 in Seattle by a man named Chin Chun Hock, who came to the city in 1860, “probably the first Chinese to settle in Seattle.” At that time there were but 302 people in Seattle’s King County.

Following the establishment of the company, Chin Chun Hock was referred to as Wa Chong. His business was so successful that he expanded to “two other metropolises in the Northwest: Portland and Butte.”

Wa came to Butte in October 1898 and the Miner reported him saying it was “a great city and I always like to come here.” He let his political views be known as well, saying, “I look for a revolution in China in the very near future. The people who know anything at all over there will lead the more ignorant masses against the officials, and I look to see the present government overthrown.”

Wa’s Butte building was completed in 1899 on 49 West Galena Street and in 1909 he came back to build another company building at 15 West Mercury, or at the corner of China Alley. In 1911 the buildings on Mercury Street were worth $25,000 and Wa owned $8,000 of that.

Montana’s Chinese in the Early-20th-century

By 1920 just 101 Chinese lived in Helena. By this point the employment broke down like so:

- 18% were truck farmers

- 18% worked in restaurants

- 15% owned a business of some sort

- 15% were laborers

- 10% worked in laundries

In 1930 there were 88 Chinese in Helena. By 1940 there were 50 and by 1970 there were only 31. Those numbers went up slightly so that by 1980 there were 49 Chinese in Helena and in 1990 a total of 50.

We know that in 1900 a total of 91% of the Chinese could read and write and 70% could speak English. By 1920 80% could speak English.

One Chinese man that came to Montana was named Wong Sun.

He came in 1927 and established the Wong Sun Company in Billings. It was an herbs shop and Sun had 22 years of experience “absorbing the knowledge of old China, and studying the science of herbology,” according to newspaper article from September 1938.

The going was tough at first and Sun “received little more than existence from his business that year.” Eventually word got around that Sun’s herbal remedies were good cures for what ailed you and business picked up. By 1937 he’d opened shops in Missoula and Great Falls.

Not all Chinese-Americans were as successful or stayed as long as those in Montana. A good example of this is the Chung family.

That’s an image of Mrs. Wah Chung holding her infant son Sammie. She was the wife of Wah Chung, who in the late 1880s was a prosperous Southern Pacific labor contractor in Ashland, Oregon.

He supplied the railroad with Chinese laborers. Mrs. Wah Chung came as a mail order bride and was an exotic figure around Ashland, dressed in Chinese silks and brocades.

After her husband died, Mrs. Wah Chung and Sammie moved to Portland. Later Sammie apparently drowned in the Willamette River and his mother made plans to return to China.”

Montana’s Chin Family Runs Into Problems

In November 1937 there were raids by the Feds in Butte and other major US cities. They were looking to break up the opium smuggling ring and Wa’s son was arrested.

By this time Chin Yee Fong was known as Albert Chinn and the feds alleged that he’d been running “the hub of the distribution system controlled by the Chinese tong” that distributed opium.

Albert Chinn was known as Chin Joo Hip when he sold drugs and his son, Chin Joo Hop the younger (Howard Chinn to everyone else) was also in on it.

Both father and son were released on bond though Albert was convicted of the charges and served two years at California’s Terminal Island federal prison. When he got out in October 1939 he went back to Butte and opened the Mai Wah Noodle Parlor in 1942.

It’s not known when this new business or the Wah Chong Tai mercantile company were closed, but it’s assumed it took place between 1943 and 1945. When Albert Chinn died is also uncertain, though it’s suspected it was around the time his son William Chinn was fighting for the U.S. Army in the war. William came back to Butte in 1945.

The Chinese of Blackfoot City

Poker Jim

Poker Jim Unfortunately, there’s not much more in the Montana Historical Society files to prove this.

One thing they do have, however, are stories from Blackfoot City.

Blackfoot City was an area of today’s Powell County that was thriving as a gold mining community in the 1880s. One woman named Hattie McIntosh – called “Toots” by those who knew her – lived there. Years later Toots told her daughter in law her stories.

One involved two Chinamen that lived in Blackfoot City named Ah Soo and Ah Jim. The two usually were called Soo and Poker Jim. They lived on Carpenter’s Bar, an area that was mined at that time, though they never talked to one another. “The popular explanation was that they belonged to different Tongs and this was the reason for their enmity,” we’re told.

Soo was a friendly man that liked to laugh and when he did so you could see his two teeth, one upper and one lower. “A traveling dentist had persuaded Soo to have all of his teeth pulled and had promised to come back and finish the job, but he never returned.”

Soo did laundry and “mined some in his later years,” though never had much money. When he couldn’t work any longer he received $8 a month in welfare from the county commissioners. We’re told this was “more than adequate” as Soo could buy 100-pound bags of rice which he “supplemented with wild game and vegetables.”

As the years wore on so did Soo. He lived to be 100-years old and was looked after by both the McIntosh family and the Allen family. On one occasion Soo heard a neighbor’s daughter was having nosebleeds so he took some firecrackers over and “set them off on the front lawn to drive the evil spirits away.”

When Soo finally died in 1926 or 1927 he did so in his “cabin near the road.” He had set aside “five or six welfare checks for his burial,” which took place in Deer Lodge.

Poker Jim, on the other hand, “was not very friendly and rarely spoke.” He was a miner that worked for someone named Jim Allen. We’re also told that Poker Jim had a wife named Katie.

Jim originally lived in a dugout 300 yards down the mining bar though later moved to Blackfoot City “and lived in a cabin south of town near the dump.”

Frontier Town’s Jon Quigley knew Poker Jim well and often took some food to the old man.

Quigley was but a teenager at the time but Jim trusted him and “showed John his opium pipes and his daggers and even showed him the proper way to use a dagger.”

Here’s how Poker Joe’s end is recorded:

“When Poker died [in 1927 or 1928] John was in Deer Lodge going to high school. John couldn’t get home right away, but when he did he went to Poker’s cabin. It had been completely ransacked and nothing of value was left.

John was terribly disappointed, but then he remembered that people often hid their valuables under the floor of their cabins. He began to kick the dirt and rubble aside and found a loose board. Under the floor he found a tin box. When he opened it it appeared to be full of fine dirt.

He began to poke around in it and discovered there were various objects in the box. Then he picked out a stout stick which was near the top of the box and began to move things around with it. He noticed the stick had little gold dots along one side.

He found the daggers and the opium pipes and some Chinese coins. Then he dumped the whole thing out on the floor. He put the daggers, opium pipes, coins and the stick back in the box and took it home. The stick turned out to be Poker Jim’s gold scale.”

That, however, is a story for another day.

Notes

Anaconda Standard, 12 January 1894.

Bik, Patricia. “China Row: A report on the Chinese burial ground at Forestvale Cemetery for the Forestvale Cemetery Board of Lewis and Clark County.” Montana Historical Society report, December 1993.

Billings Newspaper (no name listing), 19 September 1938

Gibson, Richard I. “The Chinn Family Butte, Montana.” Montana Historical Society report, January 2013.

“Gold Mountain.” The Madisonian. Special Edition: July 1989.

Helena Daily Herald, 7 July 1870.

Helena Daily Independent, 2 February 1909,

Helena newspaper (name not listed), 24 January 1866

Medford Mail Tribune, 9 April 1989

Montana News Association, 9 June 1941

“Tales of Blackfoot City as Heard by Alice McIntosh.” Oral history at the Montana Historical Society, Chinese in Montana folder #2.

The Butte Miner, 23 February 23 1908

The Eighth Report of the Bureau of Agriculture, Labor and Industry, November 1902

The Montana Post, 3 June 1865

Wunder, John R. “Law and Chinese in Frontier Montana.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History. Vol. 30, No 3. July 1980.