There’s not much information on those signs about Francois Finlay, or Benetsee as he was commonly called. Most books on Montana history mention him only in passing, and in not a single one did I find a date for his birth or his death. It wasn’t until I was digging through the Montana Historical Society archives a few weeks ago that I stumbled upon an old oral interview from the 1940s that provided a lot more insight. Portions of the interview are presented below in block quotes, as well as other information about this interesting figure in early Montana history.

Francois Finlay’s Life as Told by His Son Peter Finlay

No doubt some of the information was lost in translation, and the man might have been prone to embellishments, but much of his accounts of his father match the historical record, as limited as it is, and actually add to it.

Francois Finlay’s Early Life in Montana

It was held that Francois Finlay was born in Canada, but his son Peter’s account leads us to believe that just isn’t the case. Instead Finlay was born on the Tobacco Plains of what is now Eureka, Montana.

We know what Francois Finlay looked like from his son. Here is how Finlay described his father:

He was avery [sic] intelligent man and could read and write and the Indians of this western country, all of whose languages he could speak, trusted him implicitly. “Benetsee” was always called upon to settle disputes, for they recognized him as being fair and square in all things.

He was a big man in every way, about six feet in height, with piercing dark brown eyes that could flash fire at times, although he was of a gentle nature. He had shaggy hair and eyebrows like his Scotch ancestors, and a deep, broad chest. He had a mustache, but no beard. His appearance was always neat and he kept us that way when he was around, yet he was always kind and considerate, if firm, and was a hard worker and a mighty good provider.

An Indian at Heart

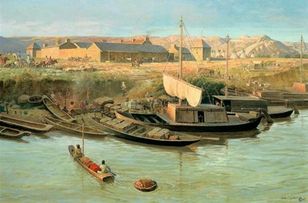

Francois Finlay, or Benetsee, after exchanging his colored clothes, beads, powder, lead, and what-not (perhaps whiskey) with the red wanderers of the west, for furs and buffalo robes, became so prosperous that he bought a large drove of horses in California and brought them to Deer Lodge Valley. How many years passed in such occupations, history recordeth not; but it is known that Benetsee went to reside in that pleasant place in Montana sometime prior to 1850.

Peter Finlay recalled that time in his father’s life this way:

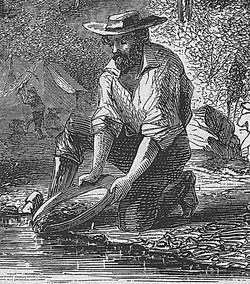

I was but a year old when my father went to California to seek his fortune in the gold diggings. Of course, I do not remember anything about those days, but it was there he had his first experience in placer mining. He did not make much of a stake and soon returned to the land of the open range – the land of his fathers.

Finding Gold in Montana

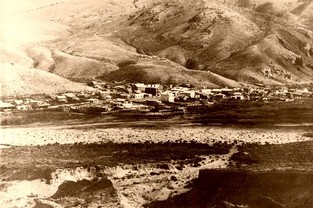

Old mining equipment in Gold Creek

Old mining equipment in Gold Creek

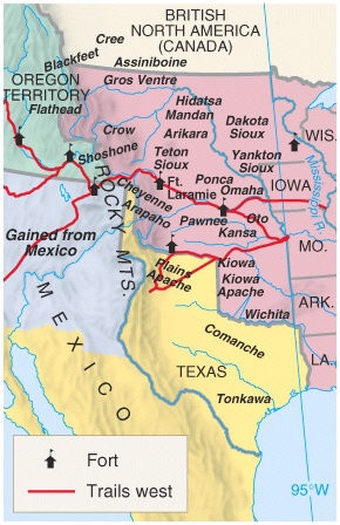

After getting a pan he proved lucky, finding about a “teaspoonful of yellow grains,” according to Stout. Finlay knew of a man that could help him, Angus McDonald, the chief trade agent for Fort Connah, a Hudson’s Bay Company trading post just south of Flathead Lake that had been established in 1846.

McDonald was no expert on gold, but he knew it when he saw it and bought up what Finlay had right then and there. In exchange Stout tells us that Finlay received a “month’s provisions and necessary miner’s tools.”

Finlay headed back up to his creek and continued with his diggings. He managed to find another two ounces of gold but after that both he and McDonald grew weary of the work. Finlay no doubt wanted to get back to his nomadic ways, while McDonald may have been feeling pressure from his Hudson’s Bay superiors, many of whom thought gold prospecting would interfere with their main trading interests.

The fur industry was feeling pains, and had been for years. The fur industry had really dried up when fashion sensibilities in Europe changed around 1840. Those in the business knew that if word of gold got out there’d be a rush to the area and their already perilous existence would be finished. Finlay was encouraged to keep his discovery quiet, something he had no problem doing.

Peter Finlay recalled his father’s discovery of gold like this:

I was but four years old when he prospected for gold, as he did as often as he took the notion. He found some in 1852 on what was then called Benetsee creek – now called Gold Creek – more gold than he was every [sic] given credit for, for it was kept as much of a secret as possible, as I have mentioned before. He took it to Angus MacDonald, who at that time was engaged in the fur trade, and, like all the fur traders, feared that the news of the discovery of gold would bring in a horde of whites and thus ruin his business. He urged my father to keep the matter quiet, which he did. How much he got out of MacDonald I do not know, nor did he ever tell me, but it must have been quite a grubstake.

My father did return to his diggings and washed out more gold. Some of it he traded for supplies at Fort Owen and the rest he left with the company. It must have amounted to over $1,000.

He tired of his labor in the placer diggings, however, and returned to the life he really loved, guiding and packing, and spending the rest of his time with the Indians he loved and who loved and adored him.

Francois Finlay’s Later Life and Death

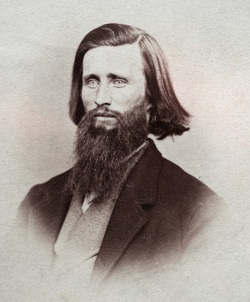

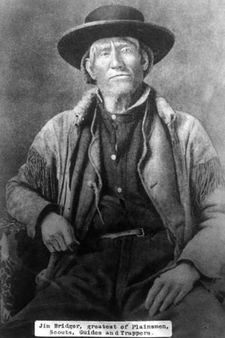

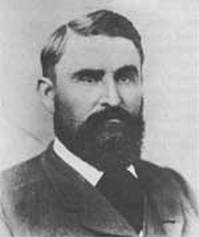

Granville Stuart, c 1890s

Granville Stuart, c 1890s

The great grand-father of Francois Finlay, Zephyre ‘Swift’ Courville, reported that Finlay had at least 200 descendents scattered around the area that would later become the Flathead Indian Reservation.

News about Finlay’s find would eventually trickle out, however, and in 1856 another find would take place. At that time Robert Hereford, John Saunders, and Bill Madison were heading from the Bitterroot Valley to Salt Lake when they decided to stop in at the creek.

Most likely they’d heard of Finlay’s discoveries during their winter trading with the Indians of the valley, and it proved worthwhile; they found some gold dust which they then gave to Johnny Grant.

It was this gold that Grant would later show to the Stuart brothers, which he always proclaimed to be the “first piece of gold found in the country.”

The Stuart brothers were James and Granville Stuart, two men that moved to Montana early and had long histories with the territory and state. In a note in his 1876 journals Granville Stuart writes the following about Francois Finlay:

Francois Finlay, better known as ‘Benetsee’ perhaps did find a few colors of gold in Benetsee creek, but his prospecting was of a very superficial nature and he was never certain whether he had found gold or not. I first became acquainted with him in November, 1860. I had located at a point where the Mullan road crosses Gold creek; a village of Flathead Indians camped near me and with them was Benetsee, who made himself known to me. Naturally our conversation was about gold in Gold creek. I asked him if he had ever dug a hole and he said ‘No, I had nothing to dig with, and I never cared to prospect.’ I am certain that this was true, because although we prospected on Gold creek and in all the gulches and streams leading into the creek, I never found the slightest trace of holes being dug or of any prospecting being done and the slightest disturbance of the sod would be noticed by us at that time…He lived with the Indians and, as the Indians, lived by hunting. He roamed over the Flathead country as did the Flatheads, going out to the plains to hunt buffalo and returning, after the hunt, with the Indians. I saw him occasionally so long as I lived on Gold creek, but when I left there in 1863 I lost track of him.

I was about 27 or 28 years old when father dropped dead at the home of my sister Ellen [Moran] near Frenchtown. They had a ranch there. He dropped dead on the way from the house to the barn. I am not quite sure, but I believe this was in 1876.

One side of him wanted to find gold, to seek it out like those in California were doing. The other part of him wanted to give it all up and travel about. In the end his Indian half won out.

The same can’t be said for Montana. By 1862 John Mullan had heard word of Finlay’s find when he was moving through the area constructing his road. By 1862 the men were taking out “about ten dollars per day.”

Mullan was the first to name Bentesee Creek as Gold Creek and he began spreading the word. The news that the fur company agents wanted to keep so quiet was now out in the open, and everything would soon change.

Bagley, Will. Visions Bright Before Them: Trails to the Mining West, 1849-1852. University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 2012. Retrieved 4 September, 2013, from http://books.google.com

Finlay, Peter. Personal interview by Griffith A. Williams. 10 Feb. 1942. Montana Historical Society, Helena.

Stout, Tom (ed.). Montana, Its Story and Biography: A History of Aboriginal and Territorial Montana and Three Decades of Statehood. American Historical Society: Chicago, 1921. p 184-89.

Stuart, Granville. Forty Years on the Frontier. Paul C. Phillips (ed.). University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1977. p 137-40.