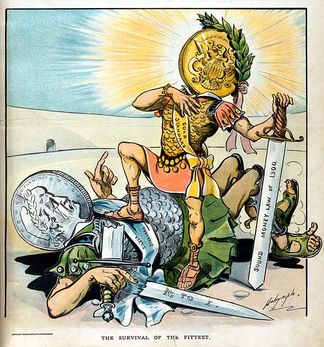

That small number is rather surprising, and is one possible reason for the troubles that came about with silver in the 1890s. In 1873 the Fourth Coinage Act had been passed by Congress, which effectively put the nation on the gold standard and demonetized silver. Many mining interests in the West called it the “Crime of ‘73” and it would become a leading issue of the Populist movement in the two decades to come.

Back in Montana it just meant trouble for silver producers, but that didn’t stop them from digging the metal from the ground. For many it just meant diversification and gold mining operations as well.

Thomas Cruse was a big winner outside Helena in the mining town of Marysville. He started his Drumlummon mine there in 1876 to look for silver, and by 1883 had sold it to British interests. It would yield more than $16 million over time, making it the richest of Montana’s gold mines, and one where silver had become secondary.

The true height of silver mining in Montana was 1890, although things had been rocky from the start. Right as Montana was getting going with its silver operations the rest of the world was doing the same. As supplies of the metal grew demand fell and so did prices. What was fetching $1.30 an ounce in the 1870s was only getting $0.93 by 1889.

There was just no way that could last forever. While Montana silver miners were happy, the federal government ran out of gold to back up the exchanges. Bonds bought with silver were now being questioned as well, especially since they had high interest rates which were now worthless.

The Barings Crisis

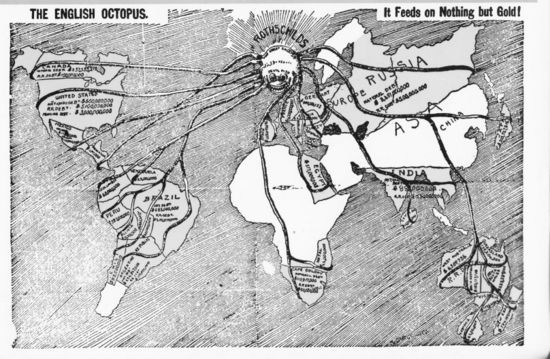

Like many rich and spoiled brats with huge annual incomes that dwarfed their countrymen, Baring thought he could do anything. In 1886 he floated shares of beer-maker Guinness and raked in 500,000 pounds sterling for himself and his banking friends. It also made him overconfident, thinking he could succeed anywhere simply because of his name.

He invested two million pounds into the Buenos Aires Water Supply and Drainage Company and then ran into problems. As many South American investors have found out over the years, politics can be dicey in that part of the world. When a military coup took place Baring couldn’t sell the shares at a time when interest rates were rising.

It was a recipe for disaster, and the British government knew it. They stepped in and bailed-out the ‘too-big-to-fail’ bank to the tune of seventeen million pounds sterling, or nearly £1 billion today. The reasoning was simple at the time – if measures weren’t taken a larger economic catastrophe could come about.

Instead a smaller, but perhaps more prolonged catastrophe came about. World markets were shocked by how brazenly England had behaved, especially the government propping up a private institution like that. When investors are shocked they often become mistrustful and then they sit on their money. This caused the inflation problems of Brazil to blow up into a bubble and it pulled in Uruguay as well.

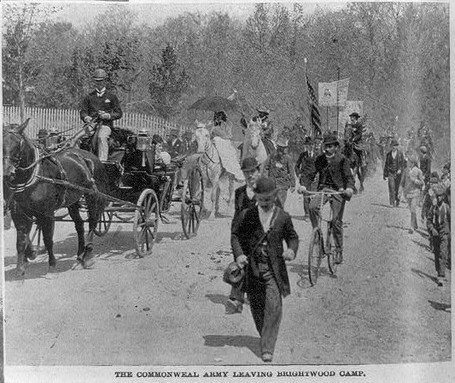

Workers went on strike, resulting in “Coxey’s Army” riding to Washington, a group that included many from Montana. Strikes in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Illinois between miners and owners were some of the most violent. The Pullman strikes later that year crippled the nation’s rail transportation system.

Silver Takes a Hit

Things couldn’t last forever with that kind of policy, not when countries around the world were acting sensibly. Investors flocked to gold, Great Britain stopped producing silver in India, and Germany made changes to its monetary system. All of that happened in mid-1893 and the price of silver plummeted to $0.62 an ounce, the lowest ever. Panic hit.

People blamed both the Sherman Silver Purchase Act and the McKinley Tariff for making the panic worse. The president had to ask J.P. Morgan for a $65 million loan just to keep the government’s promise on silver. It was a terrible mess.

The 1894 Elections

The people knew who to blame in the 1894 elections and Democrats lost overwhelmingly. It was the largest Republican election gain in history, and they swept into the White House and both houses of Congress.

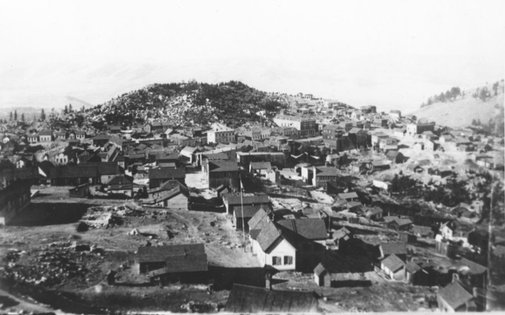

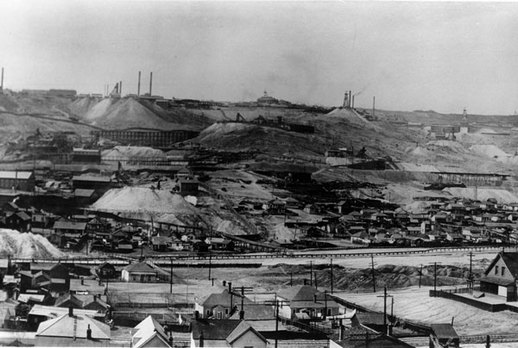

The Panic of 1893 and the Montana Mines

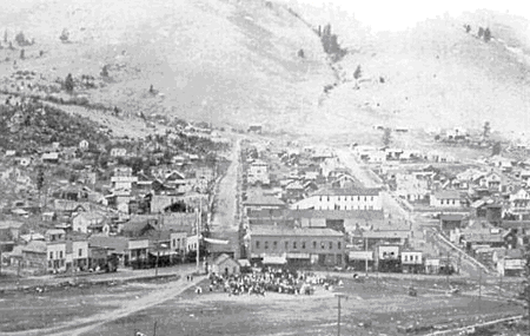

The silver town of Granite is a good example. The mining community sprang up in 1875 after silver had been discovered there, and $40 million worth of the metal came out of the ground over the next two decades. More than 3,000 people called Granite home, and it was complete with its own red-light district, Chinatown, and newspaper.

Silver mining camps and towns joined old gold haunts as the dying carcasses of past Montana industries now dotting the landscape. Silver would never again be a viable long-term business in Montana, at least not by itself. The copper mines bought them up and folded them into their operations. It would take until 1898 before the state was back on an even footing.

The Panic of 1893 and the Montana Banks

Since Helena had far more capital reserves than cities such as Spokane, Seattle, and Salt Lake City it meant things were going to be rocky for some time. Indeed, in 1889 Montana was second only to Massachussets in the amount of capital invested in national banks per capita. When the Panic hit a lot of that money simply vanished.

Not much could be done about the Panic of 1893, however, and Chicago Joe lost everything but the Red Light. The Coliseum had already been losing popularity for the past few years, what with more families coming and a great reliance on business and banking over mining. Now she and Black Hawk had to live in rooms above the saloon, just like many of the common girls she employed.

Helena’s prostitution business would continue to thrive as the decades pressed on, and the last brothel finally closed in 1973.

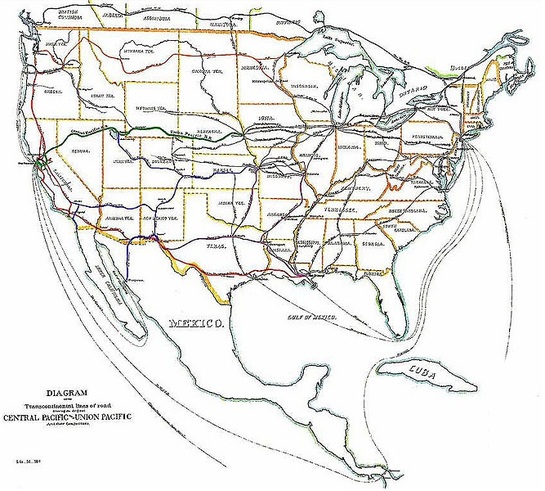

The Panic of 1893 and the Montana Railroads

The Panic of 1893 slowed things down, but unlike other railroads in the country, it didn’t stop Hill. When the Panic of 1893 hit, Hill did the exact opposite of what most were doing – he remained calm and levelheaded. He could afford to. First of all, his assets were immense and his levels of debt small. Next, he’d financed his company as it went, rolling back the profits into the business. His earlier choice to avoid the eye of government in regard to monopolies may have actually saved him.

But Hill’s business was dependent on affordable shipping to farmers, many of whom were now being hit hard by collapsing markets. He made life easier for them by lowering the tariff rates on shipping and also offered credit to many businesses that were ready to fail. Those businesses could stay open and pay their workers, and that meant more money would go back into the economy, just what the country needed to get out of the crisis.

All of it allowed Hill to come out of the Panic of 1893 in one piece, and even stronger than he’d gone in. Most transcontinental railroads failed, and monopolists like Hill were ready to buy them up.

Now there could be another connection with the west coast as well as Denver and other central locations in the country. Hill set to work buying up the Burlington, something he finally accomplished when the Great Northern-Northern Pacific finally purchased it in 1901.

All of that work made him wealthy. By 1900 he had more than $10 million to his name, and by 1910 it was $17 million. Many people in the Northwest were at the mercy of men like Hill. While it’s true Hill and others brought business to Montana and other western territories and then states, they also forced those areas into a subservient position.

It also ensured Montana and other states’ economies would be solely extraction-based. Whether it was timber or metal, the materials would be taken from the earth and shipped out of state. Rivers would be used to harness electricity and the plains would be tamed for agriculture. Government services would rise up to support that model, not find ways to replace it.

And why would they want to? There was more than enough metal in the earth and trees in the forests to last forever, wasn’t there? It sure seemed that way in the 1890s, and the idea of conservation and protecting nature was still in its infancy. In Montana it wasn’t thought of at all.

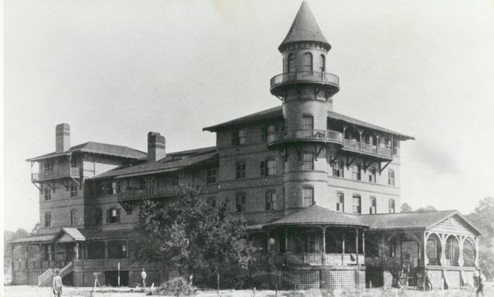

James Hill certainly wasn’t thinking about it. Unlike many robber barons of the time, Hill wasn’t much of a philanthropist. Hill knew what to do with his money, and that was spend it lavishly. He spent three years building a 36,000 square foot house in St. Paul, one that employed more than 400 workers and cost $930,000. It was completed in 1891 and would have cost more than $23 million in 2013 dollars.

For them, expanding the business interests of the United States was the most important thing, issues like overseas imperialism and free silver not so much. Many businessmen like Hill held these views, and they felt that a level playing field for business was best, which required the government to be both free of corruption and unjust regulations such as those that would eventually go against monopolies.

Unlike other rich businessmen in Montana, Marcus Daly especially, Hill never gave much to any political campaigns. Later in life he supported the Republican presidential candidates, such as William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft.

His views would have been in line with many of the other members of the Jekyll Island Club that met on the island of the same name in Georgia. Also called the Millionaires Club, the club was founded in 1886 and included some of the wealthiest families in the country like the Morgans, Rockefellers, and Vanderbilts.

Fay, Stephen. The Collapse of Barings. W.W. Norton & Company: New York, 1996.

Harvey, Mark. “James J. Hill, Jeannette Rankin, and John Muir: The American West in the Progressive Era, 1890 to 1920.” Western Lives: A Biographical History of the American West. Etulain, Richard W. (ed.) University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, 2004. p 283-6.

Hyatt, H. Norman. An Uncommon Journey: Book One in the Quaternion of the History of Old Dawson County, Montana Territory, the Biography of Stephen Norton Van Blaricom. Sweetgrass Books: Helena, 2009. p 335-9.

Malone, Michael Peter; Roeder, Richard B.; Lang, William L. Montana: A History of Two Centuries. The University of Washington Press, 1976.

Malone, Michael P. The Battle for Butte: Mining and Politics on the Northern Frontier, 1864-1906. The University of Washington Press: Seattle, 1981. p 187-200.

Malone, Michael P. James J. Hill: Empire Builder of the Northwest. University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 1996.

Marin, Albro. James J. Hill and the Opening of the Northwest. Minnesota Historical Society Press: St. Paul, 1991.

Morgan, Lael. Wanton West: Madams, Money, Murder, and the Wild Women of Montana’s Frontier. Chicago Review Press: Chicago, 2011.

Morris, Patrick F. Anaconda, Montana: Copper Smelting Boom Town on the Western Frontier. Swan Publishing: Bethesda, 1997.

Morrison, John & Morrison, Catherine Wright. Mavericks: The Lives and Battles of Montana’s Political Legends. Montana Historical Society Press: Helena, 1997. p 43-56.

Petrik, Paula. “Parading as Millionaires: Montana Bankers and the Panic of 1893.” Enterprise & Society. Dec 2009

Stout, Tom (ed). Montana, Its Story and Biography: A History of Aboriginal and Territorial Montana and Three Decades of Statehood. The American Historical Society: Chicago, 1921. p 300-15, 404-16.