Before I do that, however, I’d like to give you a taste of what I can do.

Lots of people like my historical writings, though my history books don’t sell that well.

I have six of them on the State of Montana, and what you’re about to read will be in the seventh and final volume.

I hope you’ll check these books out, especially the later volumes that deal with our more modern Montana history.

Thanks for reading!

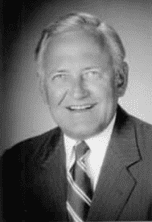

Jim Waltermire and the 1988 Governor’s Race

That was the day Jim Waltermire’s twin-engine Cessna 310 “slammed into a field near East Helena and disintegrated,” newspapers reported two days after the event.

He’d been returning from the Lincoln Day Dinner in Glasgow and was just 4 miles from the Helena airport’s runway when it happened. Also killed in the crash was pilot James A. Morris, who was 64-years-old. Waltermire had only been 39-years-old.

It was just a month before the 1988 gubernatorial primary and things would have turned out a lot differently had Waltermire not died in that plane crash.

Waltermire was the front-runner in the GOP primary that year, having announced way back in October 1987. His main platform was “advocating a sales tax and the takeover of some government services by private enterprise.”

Jim Waltermire had been born in Choteau to a “barn-storming crop-duster” father, though the man had left when he was about 5-years-old. His mother was a waitress and to help out Waltermire “peddled seeds, cards, and Grit newspapers door to door,” even “dug graves, fed cows and worked in a drug store at the airstrip.”

He went to MSU for a time, then UM, earning a business degree from the latter. He was active in supporting Nixon during his college years, then after feeling depressed by the national 1976 election returns and also feeling frustrated by the “no growth and liberal, big-spending attitudes of local governments” in Missoula, he decided to run for one of the Missoula county commissioner seats.

He had a bit of name-recognition from his investment firm Waltermire and Hicks, and that probably helped. He won the race in 1977 and was on his way.

In 1978 he decided to run for the western district U.S. House seat, and defeated four other GOP candidates in the primary, including the wife of news broadcaster Chet Huntley.

It wasn’t Waltermire’s year, and Pat Williams defeated him to take over the seat that Max Baucus was vacating.

Waltermire came back two years later, however, and won Montana’s Secretary of State race. That was the first time a Republican had done so in 48 years. Voters approved of his performance and he got reelected in 1984.

Admirers called him a “savvy, hard-charging leader armed with a vision, a record of accomplishment and the guts to make the unpopular decisions needed to move Montana forward.”

Waltermire’s foes called him “an arrogant, ruthless opportunist,” who “shamelessly” exploited the Secretary of State’s Office “for seven years to build up his name and political machinery to run for governor.”

Friends admitted that Waltermire “could be brusque” but that his “perceived arrogance and aloofness masked a shyness, a sensitivity and a sense of insecurity from growing up in a financially struggling broken home.”

The public didn’t really get a chance to see the warmer side of Waltermire, friends said. Mostly they saw how uneasily he dealt with others, his lack of socializing, and of course that ambition.

He’d flirted with the idea of getting out of politics in 1986 when he got married. It was around the same time he converted to Roman Catholicism, something many said was “politically motivated.” Waltermire just said that it “changed his life,” gave him a “sense of inner peace,” and “made him care more about other people than himself.”

Waltermire stayed in politics, announced his bid for the governorship in 1987, and then just like that, six months later he was lying dead in a field east of the Helena airport.

No cause was ever determined for the accident, though it’s suspected that a “severe springtime storm” may have contributed to the crash. “It was snow and sleet and fairly high winds,” officials said.

The other two candidates in the GOP gubernatorial race that year – former state representative from Havre Stan Stephens and sitting Billings representative Cal Winslow – halted their campaigns.

Both had been at the same Lincoln Day Dinner in Glasgow that Waltermire had attended. “Jim was a friend of mine,” Stephens said of Waltermire, “and he was a worthy contender for governor.”

The truth was that Waltermire was in the lead going into the GOP primary and, with the state coming off 16 years of Democrats in the governor’s office, it was almost a given that whoever the Republican candidate was, they’d be winning that office. Waltermire’s death, though tragic, was a boost to Stephens.

More than 400 people attended Waltermire’s funeral the following Wednesday. By Thursday it was back to the campaign trail.

Stan Stephens Takes the Reins

Stephens had been born in Canada on September 16, 1929. He dropped out of Western Canada High School during his senior year, mainly because “his dad was sick, his mother was supporting the family.” His dad had Parkinson’s.

To help out, Stephens took work as a news writer and announcer at Calgary radio stations. “It was time for me simply to get out and go to work,” he said years later of the decision.

Stephens didn’t come to America until 1949, and he did so “in search of greater opportunities.” To find those opportunities he hired on with a “travelling farm crew that did harvesting from Texas to Montana.”

When Stephens saw an ad from Havre radio station KOJM “looking for a writer and an announcer,” he went for an interview and got the job. The salary was $175 a month.

Stephens was still a resident alien when the Army drafted him for the Korean War. Writing years later, Stephens said that he “could have refused on the grounds of being a foreign citizen.” He chose not to, however, because he’d “already decided to apply for citizenship” and “felt the same obligation as any other American when called upon to serve.”

He served as a military correspondent with the Armed Forces Radio Service and Military Intelligence division from 1952-53 and at war’s end, headed back to Havre and his radio station work. He also became a U.S. citizen in 1954 when District Judge C.B. Elwell swore him in with several others.

Stephens continued on with his work at KOJM. He “did a little of everything – writing, selling ads, announcing sports and even won a trip to New York in 1951 as Montana’s top disk jockey.”

As half of the “Bob and Ray” comedy team that appeared on the air every morning, Stephens built up a great deal of speaking experience and knowledge of the state. By 1965 he was co-owner of the station with two other colleagues.

Stephens’ reporting career got a boost when he won an Edward R. Murrow award for his reporting of improprieties in the state’s worker’s comp system in 1975.

Shortly after that he branched-out into TV, eventually becoming the president and general manager of Havre, Glasgow, and Sidney TV stations. He also got into politics.

He’d been elected to the Montana Senate in 1968, the first Republican from Hill County to earn that honor in more than 40 years. He served a single term before suffering defeat in the 1972 election, mainly due to the reapportionment of the district.

When district lines were again redrawn in 1974, however, he won the seat back and served in it until 1987. In 1979 and 1981 he was the body’s majority leader, became its president in 1983, and when Democrats took over in 1985, became the minority leader.

Democratic legislator Chet Blaylock said that Stephens helped control “the far-right-wing nonsense that sometimes came out of the GOP House.”

Coal industry lobbyist Jim Mockler called Stephens “a tenacious little devil” and that if his ideas didn’t get approved the first time around “they’ll resurface in another way later.”

Stephens’ political opponents in his Montana Senate races didn’t like the fact that he controlled the media stations, and claimed it gave him an edge. They charged that he allowed himself to buy a lot more ads than he allowed them, and the ads he did give them ran at odd times. Stephens refuted this, and also pointed out that the FCC “carefully monitored the station.”

What helped Stephens most of all, however, was his “experienced radio voice, speaking ability and knowledge of the media.” Those skills helped him on the campaign trail and they led to his decision not to run for the legislature again in 1986.

He knew he wanted something more, but couldn’t decide on governor or U.S. Senate. He finally decided that he’d do better as governor, for it’d take “10-12 years in the Senate with its seniority system” before he could affect any meaningful change.

So it was the governor’s race he set his sights on. To indicate how serious he was, he sold off his interests in his radio and TV stations before announcing.

The 1988 Campaign

Even though the Rocky Boy Indian Reservation voted Democratic 90% of the time, Stephens learned some Chippewa Cree words to win them over. “They gave me an ‘E’ for effort,” he later said. What might have helped him more were memories of him “buying coffee and doughnuts for rail workers manning a picket line.”

His main issues during the campaign were less government, fewer regulations, shrinking the state workforce, and privatizing some government services. He also wanted to reduce the forty-one classifications of property taxes to just three or four.

He thought a longer school year might benefit Montana students while higher wages for university faculty would improve the situation with the university system. One reporter said the Stephens’ campaign possessed “all the excitement of a dark business suit.”

That perception changed when Stephens got an early boost in March 1988 when, “instead of delivering a closing speech” at a Billings candidate debate, he “pulled out his trumpet.”

Stephens had learned to play the instrument from his father. He was just 6-years-old when he took it up, but by the time he was 12 he was the principal trumpet for the Calgary Symphony Orchestra, “whose ranks were depleted by men serving in the military during World War II.”

Stephens “brought 700 people to their feet by belting out the state song” that night at the debate. Stephens was later voted “the most impressive candidate of the night.”

“I have no desire to go to Washington,” Stephens said shortly before the June primary. “I want to be governor of the State of Montana, and I want to do that well. I don’t seek this position as a stepping stone to federal office. I am not on an ego trip.”

When the June primary came, Stephens took it 50% to Cal Winslow’s 43%. Winslow had campaigned on his youth and the idea that he could bring business to the state, but voters didn’t buy it.

Things had been very sketchy going in, however, and the results proved that. More than 6,000 people voted for Jim Waltermire, or nearly 7%, even though he’d died a month earlier. Had they voted for Winslow, Stephens might have lost.

On the Democratic side, six candidates battled it out, with former governor Tom Judge (who’d served from 1973 to 1981) coming out on top. He had 39% of the vote, with Frank Morrison coming in second at 27%.

Mike Greely split the more liberal vote of the Party, taking 22% of the vote and ultimately denying Frank Morrison from gaining more than the 27% he took. Morrison’s dad had been governor of Nebraska from 1961 to 1967, and though many in Montana liked his son, they felt him too liberal for the state and saw him as just another out-of-stater trying to weasel his way in.

By November voters had heard the candidates out for months and come to the decision that it was time for a new face, not an old one. Stan Stephens took the race with nearly 52% of the vote compared to Tom Judge’s 46%. Third-party candidate William Morris took nearly 2%.

Governor Stan Stephens (1989-1993)

“I simply wish I’d inherited an administration that had a reserve and a budget that was more promising,” he said.

Stephens didn’t have much money to work with and stood by his pledge not to raise taxes. Even transitioning into the governor’s office had been difficult – the state had $5,000 in funds for that but it wasn’t enough and Stephens used $30,000 of his leftover campaign money to help.

Despite those difficulties, Stephens managed to get through the legislature that year, and even called a special legislative session as well. The latter succeeded in dropping the business equipment tax from 16% to 9%.

Stephens also vetoed some spending bills, which ultimately cut the budget by $10 million. The university system saw an additional $13 million in funding, though with the stipulation that they have greater accountability as well.

By the 1991 legislative session he was ready to cut 400 state jobs while providing no increase for education funding. His total budget that year was for $1.7 billion, though that was $100 million more than the state was expecting to take in.

He also vetoed the infrastructure bill that year, saying he’d instead go with the voter initiative Big Sky Dividend program in 1992. By the close of the session, Stephens had vetoed thirty-three bills, more than the previous two governors did during their 16 years in office.

At the end of August 1991, Stephens announced that he’d be running for a second term. At the time there was a revenue shortfall of $73 million and Stephens wanted to cut spending by 8%.

“Confidence, optimism, excitement is etched on the landscape as we move on,” Stephens said during his announcement. Democrats said the governor was “an out-of-touch chief executive wearing the emperor’s new clothes and viewing Montana through rose-colored glasses.”

Dorothy Bradley, a Bozeman representative, had already made it clear she’d be running for governor in 1992. “Never in my 16 years as a legislator have we entered into a biennium with a budget in such shambles,” she said.

Stephens countered this by saying that more than 21,000 new jobs had been created in his three years in office.

Montana AFL-CIO head Don Judge said those were “low-paying, burger-flipping jobs.”

The Stan Stephens Scandals

Right away upon taking office there were stories that Stephens was going to lease a limousine to drive him around, though he adamantly denied this. There was a bit of truth there, however, for the governor sold the $32,000 Lincoln Town Car a year later and downgraded to “an economy car.”

Also in January 1989, the head of the Department of Family Services resigned after “making harassing phone calls to Stephens’ opponent in the 1988 GOP primary.”

The next month Stephens got in hot water when news leaked out that an aide was compiling “psychological profiles of legislators.” A month after that Stephens’ budget director resigned after admitting he’d falsified his credentials and had also been married to two women at the same time.

In August 1989 it was revealed that the labor commissioner had “ordered some of his department’s airline tickets be bought through a Butte travel agency owned by a nephew.”

In February 1990 Stephens’ commerce director resigned after it was revealed he’d ordered the hiring of his girlfriend and that he’d also bought label pins from a company his son owned.

Then in September 1990 Stephens made headlines by asking the Helena Department of Motor Vehicles to stay open late so he could renew his driver’s license.

“I figured if I didn’t I would have probably have got in trouble,” the examiner of the Helena office said of her decision to accede to the governor’s wishes. “I didn’t think it was fair,” she added, and also mentioned that U.S. Senator Max Baucus had “stood in line last year for the usual 20 minutes.” Stephens had been incensed at the 45-minute wait time he’d found upon coming in after the Labor Day weekend.

A month later the Highway Department director resigned after it was revealed he’d overspent the department’s budget by $20 million and twenty-nine construction projects had to be delayed because of this.

In November 1990 Stephens’ appointment to the Disaster and Emergency Services Division was suspended, and four months later, fired. Fellow workers described the man as “abrasive, overbearing, and arrogant” and that he was “prone to temper tantrums and mistreating workers.”

By mid-1991, Stephens had a 45% approval rating. More than 56% of people thought he was doing a bad job. Still, a couple months later he announced he’d be running again in 1992.

In the end it wasn’t the controversies and the opposition that took Stephens out of the running for the 1992 governor’s race, it was his health.

On January 17 Stephens stood in the Governor’s Reception Room of the State Capitol and “red-faced and shaking with anger, he blasted Democrats for what he said were personal attacks on him.”

The next day Stephens had “dizziness and brief inability to speak” before collapsing in his home. He got checked out in Helena and a further opinion in Seattle. Doctors told him he’d had a “transient ischemic attack in which part of a blood clot apparently reached a blood vessel in his brain.”

Stephens was 62-years-old at the time and was encouraged “to slow down and watch” his daily activity. He said that when it came to being governor, “there simply is no other job in Montana that has this kind of demand on the human body and on your mind.”

Although making it clear that, “I’ve been advised by a number of medical authorities that I’m perfectly capable of resuming my normal duties and running for a second term,” he decided to bow out of politics.

On Friday, January 31, he made the announcement that he wouldn’t be seeking that second term after all.

That was the first the public had heard of it. The night before, however, he’d told senior aides of the decision. One of them was Denny Rehberg.

Continued in…The Phone Call That Changed Montana

Notes

Anez, Bob. “Waltermire killed in crash.” Great Falls Tribune. 10 April 1988.

Anez, Bob. “Stan’s first weeks: no picnic.” Independent Record. 24 February 1989.

Anez, Bob. “Office open late to help out gov.” Independent Record. 14 September 1990.

Anez, Bob. “Stephens budget cuts 400 jobs.” Great Falls Tribune. 28 November 1990.

Anez, Bob. “Stan’s appointments: a comedy of errors?” Independent Record. 30 August 1991.

Johnson, Charles S. “Stephens trumpets his cause in campaign.” Great Falls Tribune. 13 March 1988.

Johnson, Charles S. “Waltermire sparked controversy, admiration.” Great Falls Tribune. 10 April 1988.

Johnson, Charles S. “Stephens liberal with use of veto.” Great Falls Tribune. 9 June 1991.

Johnson, Chuck. “Stephens listened to warning signs.” Great Falls Tribune. 2 February 1992.

Johnson, Peter. “Stephens launches re-election campaign.” Great Falls Tribune. 29 August 1991.

Johnson, Peter. “Stephens ratings at lowest level since mid-’89.” Great Falls Tribune. 23 December 1991.

Newhouse, Eric. “Stan: We need a sales tax.” Great Falls Tribune. 22 May 1992.

O’Connell, Sue. “State officials laud Waltermire.” Great Galls Tribune. 10 April 1988.

Skidmore, Bill. “Gov bows out.” Independent Record. 31 January 1992.

“Stan Stephens: Moderate Republican campaigns on ability to ‘motivate both sides.’ Independent Record. 29 May 1988.

“Stephens lists accomplishments in first year.” Great Falls Tribune. 1 January 1990.

“Through the Open Door, What Is It Like to Be an Immigrant in America?” The Wall Street Journal. 3 July 1990.