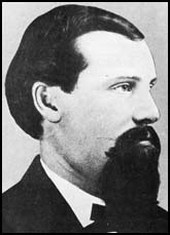

Henry Plummer

Henry Plummer

It’s no surprise then that highway men rose up in the area to take that gold off their hands. Robberies to and from the finds around Bannack, Virginia City, and the other upstart mining communities increased markedly in 1863, many of them resulting in murders.

What point was there in breaking your back in the mines if all you worked for could be taken at gunpoint? Something would have to be done to stop this, and if the local law couldn’t do it, then Montana’s citizens would take matters into their own hands, giving rise to the vigilantes.

As robberies continued and increased many in the communities began to suspect the attacks were planned and coordinated. And soon the finger was pointed at Bannack’s very own sheriff, Henry Plummer.

A Promising Young Man

By 1852, when he was nineteen years old, Plummer decided to head out to California to try his hand at gold mining. His luck proved strong and within just two years he’d managed to buy his own mine, ranch, and bakery in Nevada City, California.

Plummer was quite handsome and also very articulate. Ed Purple traveled the gold camps and described Plummer as being under six feet tall with brown hair and light eyes, which, when he grew angry, became “black and glistened like a rattlesnake’s.”

Purple goes on to describe him as speaking in a “low, quiet tone of voice, a habit which never deserted him, even when labouring under such intense excitement as the Murdering of a human being must produce.” He was also said to be quite the neat person, often being the “best dressed man in town,” according to Purple.

But when he got drunk people knew to keep their distance, especially when he began grinding his teeth, a habit which told those who knew him that he wasn’t in a happy mood. (Purple, 139)

He quickly became popular with the people of Nevada City despite his drunken behavior and by 1856 they’d elected him sheriff. So popular was he, in fact, that there was quite the talk of him running for the state assembly, the lower house of the California legislature, as a democrat, but the divided part couldn’t quite get its act together to support him.

On the Wrong Side of the Law

John Vedder accused Plummer of adultery, and their relationship quickly soured to the point that on September 26, 1857, Plummer shot and killed John Vedder. Plummer was put on trial, found guilty, and sentenced to ten years in San Quentin. He served nearly two years before the governor pardoned him, both because of the amount of letters he’d received from Plummer supporters and the fact that Plummer was suffering from tuberculosis.

Free from prison, Plummer became a citizen once more and did well for himself until 1861 when he shot and killed William Riley, an escapee from San Quentin that he’d been trying to carry a citizen’s arrest out on. The killing was ruled justified by the police, but with his earlier prison record, they advised him to leave California.

Moving On to Montana

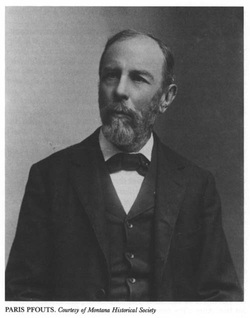

Paris Pfouts, Vigilante President

Paris Pfouts, Vigilante President

He and a horse-dealer friend from California, Jack Cleveland, made it to Fort Benton, in what was still then part of Idaho Territory. While waiting for a steamboat to take them down the Missouri River they were approached by James Vail. Vail explained that he was trying to get a mission started up in Sun Valley and wanted some protection from local Indians. Seeing as how no ships were coming through, both men accepted the offer.

And it didn’t take long for both men to quickly fell in love with Vail’s sister-in-law, Electra Bryan, with Plummer eventually asking for her hand in marriage. She agreed, whereupon they, together with Cleveland, decided to move to where gold had just been discovered the previous summer, Bannack.

Henry Plummer in Bannack

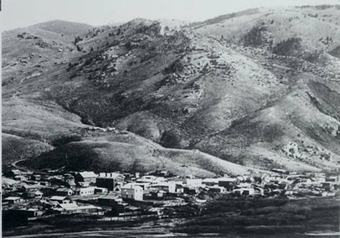

Bannack in 1880

Bannack in 1880

With that comment Plummer had had enough: he fired on Cleveland and hit him below the belt. When Cleveland fell to his knees and begged Plummer not to shoot him, Plummer told him to get, and when he did, proceeded to shoot him in the heart, the eye, and even grazed another man watching.

Nothing was ever done about the shooting, and most people had the attitude of ‘why should there have been?’ Scenes like that were a near-daily occurrence in and around Bannack, and most thought that Cleveland was to blame. After all, he’d been ready to go for his guns and shoot down some men that had supposedly already paid him.

The citizens of Bannack didn’t seem concerned with it, an even elected Plummer sheriff a few months later in May by a fifty-vote margin. Granville Stuart was one that met Plummer before he’d been sheriff, when he was first coming to Montana and stayed in Gold Creek for a time.

Plummer left a good impression on Stuart, who was also interested in the politics of the democrats like Plummer was. When he met him the following year in Bannack, however, he had a different impression. By that time Plummer was sheriff and Stuart noted that everyone in Bannack was “afraid of him” since Plummer could “get about half amuck and go and scare it straight out of them,” in reference to Plummer’s ability to collect debts.

As historian Clyde A. Milner puts it in As Big as the West: The Pioneer Life of Granville Stuart, the people of Bannack knew what they were doing in electing Plummer as sheriff, and it was exactly those qualities that scared them that they also hoped would protect them.

“They wanted someone whose experience and demeanor would enable him to control the criminal element,” Milner writes. “As the months passed, many came to believe that Plummer coordinated that element.” (p 89)

And it’s there that the story of Henry Plummer gets a bit muddled. There are two trains of thought regarding it, both plausible. In one, Plummer was an innocent sheriff of Bannack who got caught up in a wave of unlawful vigilantism and was hanged without trial. In another Plummer was hanged for being the leader of the Innocents Gang, a group that preyed on gold shipments around the territory and was responsible for more than 100 deaths.

The Innocents Gang

Virginia City in 1866

Virginia City in 1866

The group had many hideaways, but was headquartered twelve miles outside of Virginia City at the Rattlesnake Ranch and was called the Innocents Gang. The group of possibly more than 100 members preyed on miners and were so named because they’d answer to a secret password, “I am innocent.” Most knew one another by the special knot they wore in their tie and the special cut of their beards.

Plummer was known to frequent the ranch, and everyone knew him to be a good shot with his pistol. Another favorite haunt was the Cottonwood Ranch, owned by a man named Dempsey who had no connection with the road agents, but did know enough not to bother them.

The group would split themselves up into smaller units of men so they could hit different mining camps simultaneously, even having men watching out at mining offices so that they’d know exactly when gold was to be shipped out. They got most of their plunder between the seventy miles from Virginia City to Bannack.

Plummer became implicated with the gang when two residents claimed that he’d been present during their robbery. Still another claimed to have been offered some of his money returned when he complained to Plummer about how dangerous the roads were. Those cases may or may not have been true, but what was glaringly obvious was how bad the attacks were becoming, and how little was being done to stop them.

The Vigilance Committee Forms

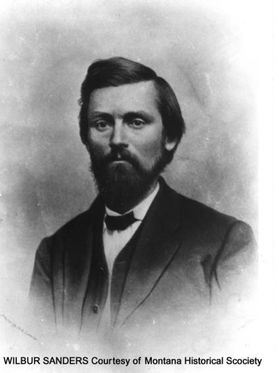

Wilbur Fiske Sanders, Vigilante Lawyer

Wilbur Fiske Sanders, Vigilante Lawyer

In December 1863, a young Dutch immigrant named Nicholas Tiebolt, or perhaps Thiebalt, disappeared. He’d had a bag of gold on him, and many suspected that he’d simply taken off with it. When his employer, William Clark, heard of it he suspected the man had been killed, however.

His suspicious proved true two weeks later when Tiebolt’s body was discovered. It was revealed that he’d been shot in the temple, although didn’t die. He’d then had his hands and neck tied with rope before being dragged through the frozen grass to die of exposure.

Tiebold’s body was discovered on December 17, and it was just four days later, on December 21, that the Vigilance Committee took revenge, rounding up George Ives, a man that had been along with James Stuart on his Yellowstone Expedition to find gold earlier that year. The Vigilance Committee suspected Ives for the sole reason that he’d acted suspiciously at the mule ranch he’d been working at.

A quick trial was held outside on the Main Street of Nevada City, one of the mining camps running along Alder Gulch. Lawyers were there to present a defense, Wilbur Fiske Sanders was chosen as the prosecuting attorney by the vigilantes, and a jury of twenty-four was chosen to decide Ives’ fate.

Twenty-three of them delivered guilty verdicts, but the last felt that not enough evidence had been presented and a hung-jury looked inevitable. The crowd, which numbered between 1,000 and 1,500 at that point, would have none of it however. Ives was strung up from an unfinished dry goods store and hanged. Two other men that’d been arrested with him, George Hilderman and John Franck, were released.

Following the incident the Vigilance Committee drew up formal papers. Twenty-four men joined right then and there, including the man who found Tiebold’s body as well as his employer. They even chose a president, Paris Pfouts. And the vigilantes quickly chose their next targets.

When Ives had been given a chance to speak before being hanged he’d said that the true killer of Tiebold had been a man named Alex Carter. A group of vigilantes rode out looking for Carter, and when they were given wrong information from a man named Red, who was actually Erastus Yeagher, they arrested him and his friend G.W. Brown and hanged them both. It would be Yeagher that would give the vigilantes most of their information after he broke down and named names.

Emboldened by their killings, the vigilantes set their sites on Sheriff Plummer. A group of four delegates from the main Vigilance Committee were sent to Bannack to discuss matters with twenty-four of the town elders. The delegates arrived on January 9 and talked late into the evening. By dusk they’d reached a decision and rounded up Plummer and his two deputies, Ned Ray and Buck Stinson.

Thomas J. Dimsdale (date unknown)

Thomas J. Dimsdale (date unknown)

But then he’d been hired by the vigilantes to write a favorable account of them, which they needed considering they were under congressional review at the time. Recent accounts, most notably by Frederick Allen in his 2004 book A Decent, Orderly Lynching: The Montana Vigilantes, cast doubt upon those assertions and put forth credible arguments that Plummer was innocent.

Whatever the case, the vigilantes had deemed Plummer guilty and hanged him dead. He’d been their sheriff, a position which carries a great deal of trust. If he was guilty, then he betrayed that trust to its fullest. If he was innocent, then the people betrayed his. Henry Plummer, the man that had come west from Maine with high hopes was swinging dead from a makeshift gallows on a freezing January morning in what would soon be Montana. He was just 31 years old.

The Terror Ends

Gallows upon which Henry Plummer was hanged

Gallows upon which Henry Plummer was hanged

Skinner had been fond of sitting atop the safe in the store built by Higgins and Worden, which contained $65,000 in gold dust. Many suspected him of being a gang member, and he and four other were arrested by the vigilantes. A quick trial was held in the store and all four were found guilty and quickly hanged.

The vigilante justice would continue until February when it died out. The roads were once again secure, which led many to believe that Plummer had been the culprit all along.

The road agents that’d been terrorizing the mining shipments suddenly disappeared. Whether Plummer was their leader is uncertain. But there were somewhere between fifteen and thirty-five other men hanged. Either the gold robbers were among them or they high-tailed it on our of the area as fast as they could.

No one can be certain how many vigilantes there really were, either. Estimates range from the dozens to the more than two thousand. As historian Michael P. Malone states in Montana: A History of Two Centuries, this suggested that “the movement was broadly popular and not the work of a small clique.” (p 8)

They did set a fair amount of order in place in the mining camps where before there’d been relatively none. Instances of vigilante justice would spring up again after Montana became a territory later that year and further into the future. Nothing, however, would compare to the killing spree that took place from December 1863 to February 1864, and which claimed their most famous victim, Sheriff Henry Plummer.

Allen, Frederick. A Decent, Orderly Lynching: The Montana Vigilantes. University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 2004. p 23-43.

Callaway, Lew L. Montana’s Righteous Hangmen: The Vigilantes in Action. University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 1997. p 60-3.

Dimsdale, Thomas J. The Vigilantes of Montana. University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 1953. p 24-30.

Malone, Michael Peter; Roeder, Richard B.; Lang, William L. Montana: A History of Two Centuries. The University of Washington Press, 1976. p 78-82.

Mather, R.E. & Boswell, D.E. Hanging the Sherriff: A Biography of Henry Plummer. University of Utah Press: Salt Lake, 1987. p 102-194.

Milner II, Clyde A. & O’Connor, Carol A. As Big as the West: The Pioneer Life of Granville Stuart. Oxford University Press: New York, 2009. p 89-92.

Purple, Edwin Ruthven. Perilous Passage: A Narrative of the Montana Gold Rush, 1862-1863. Owens, Kenneth N. (ed.). Montana Historical Society Press: Helena, 1995. p 139.