Barnes, Lichtwardt, and Strandberg Threshing machine, 1918

Barnes, Lichtwardt, and Strandberg Threshing machine, 1918

Hilda Germundson would have begged and begged her father to let her stay in Sweden, but the old man would not budge.

“But father, I love him!”

Magnus Germundson was firm – the answer was no. He’d be taking his third-youngest daughter to America with him, the same as the whole family.

The family would be staying together, unlike so many other Swedish families at the turn of the 19th century. Many were ripped apart by deteriorating economic conditions in the home country, forced to split up and head to neighboring cities or even other Scandinavian countries.

Magnus Germundson was not going to let that happen to his family. His daughter Hilda would be coming to America despite her protestations.

Six months later she’d be dead.

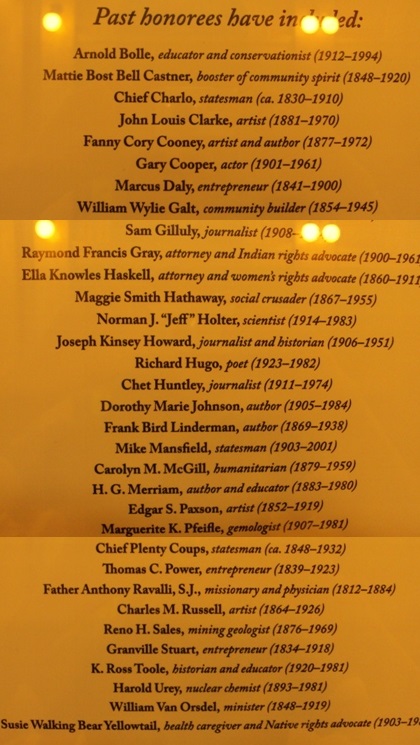

Strandbergs Coming to America

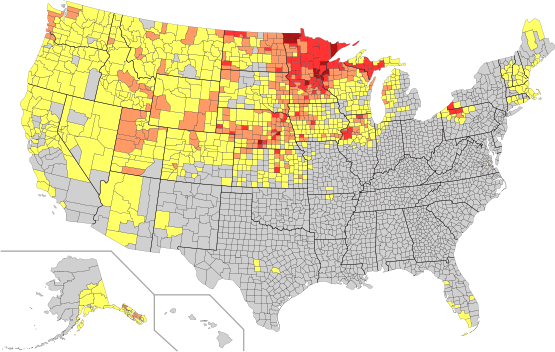

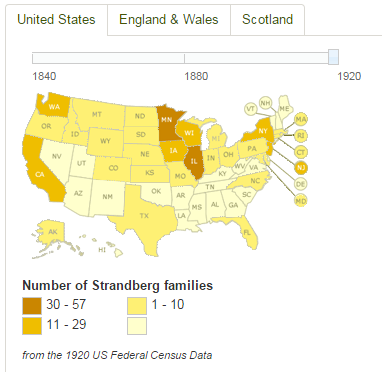

The problem quickly becomes where to look. For instance, Ancestry.com has 72,193 historical documents with “Strandberg” in the records. There are 1,479 pages of names.

One of those is Nils Strandberg. You’ll get a record of his birth and death and that’s about it, and that only if you sign up for the service.

Source Material for Strandberg Family Genealogy

Hardie Strandberg had gone to Sweden because his son, Nels Strandberg – my father – bought him a ticket as a gift for paying his first year at Carroll College.

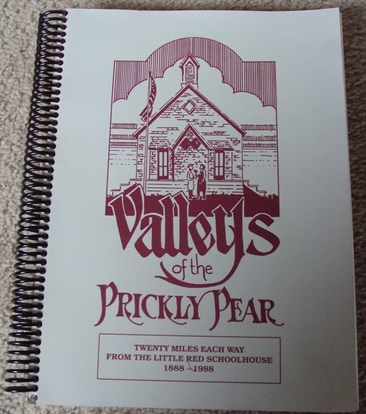

So Hardie Strandberg went over there and compiled quite a bit of history which largely remained forgotten until Wadonna Becker Ashcraft came along 1992. She put our family’s history together with other histories she’d written or collected from people like my grandfather.

The book was called Our Swedish Ancestors: Magnus Germundsson and Teadora Andersdotter (Strandberg).

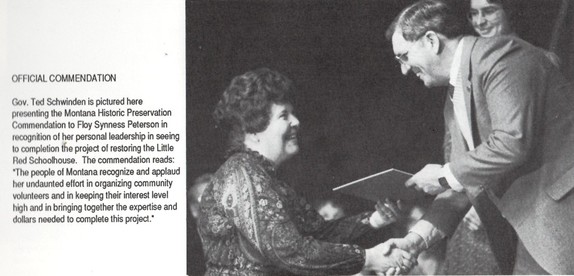

The book was largely put together by Floy Synness Peterson and Francis Isham Synness and then edited by Vivian A. Paladin.

Floy Synness Peterson was the person that restored the Little Red Schoolhouse in the Helena Valley.

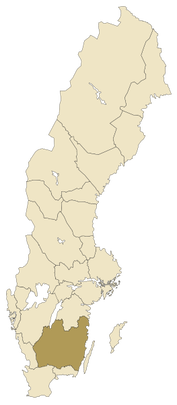

Småland, the Ancestral Lands of the Strandberg Family

Oftentimes the arms may appear with a ducal coronet, or crown. The blazon reads: “Or a lion rampant Gules langued and armed Azure holding in front paws a Crossbow of the second bowed and stringed Sable with a bolt Argent.”

There are some legends around the Småland area of Sweden where the Strandberg family of Montana hails from. One involves God creating the Smalanning people who were “strong ambitious, stubborn and shrewd.” Because the pieces of tillable ground in this area were so small the land was called “Smaland.”

Old Swedish encyclopedia Nordisk familjebok describes the inhabitants of Småland as “by nature awake and smart, diligent and hard-working, yet compliant, cunning and crafty, which gives him the advantage of being able to move through life with little means.”

In Sweden today Smålandians are viewed as very economical, “ranging from modestly frugal to utterly cheap.” The Smålandian have also been called the “Scotsmen of Sweden.”

Much of this temperament no doubt comes from the land. Smaland was full of stones so the people there had to clear the land by hand, hauling the stones to make large walls. This caused their arms to grow longer, it was believed.

If anyone was to blame for the condition of the land it was St. Peter. Here’s the story of how that went:

“The Lord was occupied with the creation of Skane, making it beautiful and rich when he directed St. Peter to bring order to the land north of Skane. St. Peter began to place a layer of soil on the many rock and stone formations. He planted pine, spruce and birch trees between the streams and lakes. He was proud of his work, but before the Lord had a chance to inspect his work a heavy rainstorm washed away the soil and made bare the long stretches of rock and boulders. When the Lord saw the stony boulders in the ground, he said to St. Peter, “I have just created a rich fruitful land to the south, you go and create men to live there. I have a much harder task here.”

Smålanders believed in the pagan gods of Thor and Odin until 1120 AD when the Norwegian king led a crusade against Småland shortly after returning from Jerusalem.

Serfdom was abolished in Sweden in the 1200s. Potatoes came to the country in the mid-1700s. It wasn’t long before herring and potatoes graced even the poorest of tables as the common fare of the country.

The Montana Strandberg Family

In 2010 the town had less than 9,000 residents. Its major claims to fame are being the home of botanist Carl Linnaeus in 1707 and the first IKEA store in 1958.

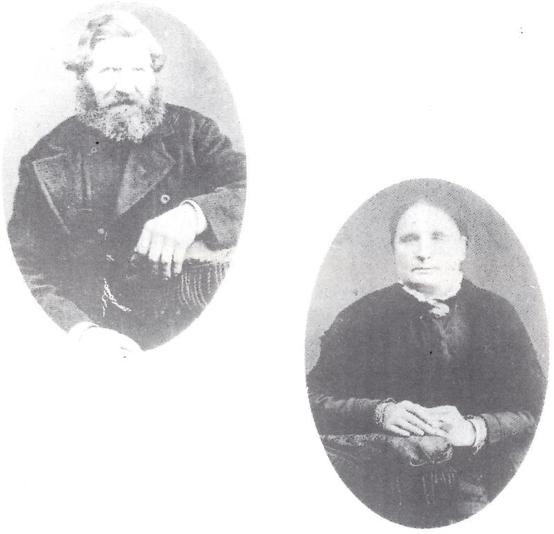

There are two main branches of the Montana and Kansas Strandberg families. First is the Magnus Germundson branch, which we can trace back to his great-great-great-great-great grandmother, Bengta Tijlsdotter. I’m going to estimate her year of birth at between 1595 and 1600. We know that her one of her grandsons was born as early as 1658.

The second branch is that of Teodora Andersdotter and we can trace her ancestors all the way back to her great-great grandmother, Lisbeth Mattisdotter. I’ll put her year of birth between 1660 and 1700. We know her son Bolla was born in 1689 at the earliest, though possibly as late as the 1750s. Most of his children were born in the 1710s and 1720s, however.

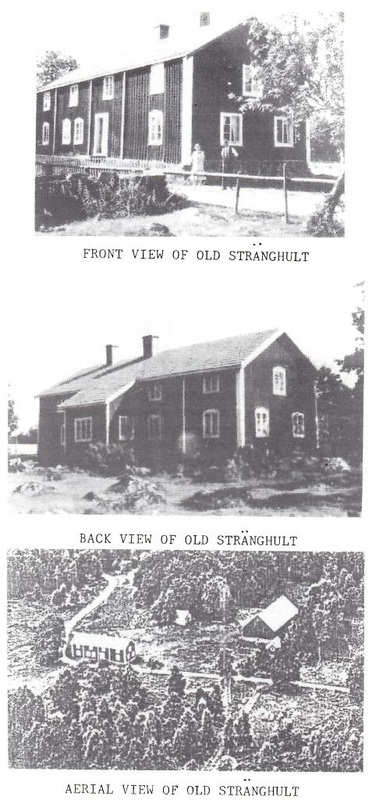

That mantle contained a farm. That farm was called Stranghult. Strangult means “string grove” or “a grove of trees” in Swedish.

The earliest date the family can be traced to Stranghult is to the early 1700s when the Anders Mattisson family is first mentioned as owning Stranghult.

Anders had six men and three women operating the farm that he had on the land. In May 1839, however, Anders died of a fever. The farm went to Bengta and her children, though it had three mortgages on it. Still, it was valued at $4,000 and had 22 head of cattle.

On September 14, 1840, Teodora was born. It was sixteen months after her mother had been widowed. So…who was the father?

Teodora was given the name Andersdotter, so we know that her father was named Anders, even though it wasn’t likely the man that had owned Stranghut and died.

It’s likely it was Anders Nilsson, who had been working at a nearby farm. We don’t know who the father was, truth be told, but the church did know that they had an illegitimate birth on their hands. Bengta had to pay a fine on October 31, 1840. In 1845 we know that 45% of the children in Sweden were born out of wedlock.

Anders Nilsson came back to the farm in 1843 to live and died there in 1854. He’d only been 35 years old and had complained of stomach pains for years.

Life wasn’t easy in Sweden. Nils Strandberg used to tell how:

“The tailor came to Stranghult each year, staying with the family while he made clothes from the woolen and linen fabric that had been spun and woven during the year. A cobbler came and stayed while he made the shoes and boots from animal skins killed and cured during the year. Nils told how as a child he soaked and laid the flax on the bank of the lake to bleach. Another story of Nils tells about how Magnus Germundsson acquired the expertise of using the new invention of dynamite. He used his knowledge and ability to blow up some large boulders from other farms in the area. Since it was such a specialized business, he was paid well and much in demand.”

This was when the mass migrations from Sweden began.

Some Strandberg Children Leave Sweden

Ingrid didn’t much care for Kansas, probably because she wanted to be in Montana. That’s where John Benson was, whom she’d known in Sweden. He’d gotten work in the Anaconda smelters and later the coal docks for the railroads. The latter proved intolerable, for in winter “his hands would freeze to the shovel tearing flesh from his bones.”

Nonetheless, he worked and the two were married in Anaconda in February 1889. There were so many “Bensons” that John Benson changed his name to John Magnus. They managed to save up enough money over time to get a stretch of land on Willow Creek, near Silver City, which is north of Helena.

By 1916 they had 100 head of cattle and Ingrid’s butter was renown throughout the area. Sadly, their son Henry was killed by lightning while working in the garden in 1920. John Magnus died in 1926 though Ingrid hung on until 1951.

“She was well known and loved in Helena. Her brother Nils Strandberg often made the remark the town people kept the road warm to her ranch. A former Governor and the Attorney General of Montana spent many days at the ranch while they were growing up.”

The Kansas Strandbergs can really trace their lineage back to Magnus and Teodora’s third child, Anna Magnusdotter. She was born in April 1865 and left Sweden on March 3, 1886. She travelled to New York, arriving on April 3. The trip cost her 167 kr.

Four others from the Virestad area of Sweden accompanied her. In New York “a black porter tried to help Anna with her luggage,” my grandfather wrote. “She refused, feeling he wasn’t clean. She had never seen a black person before.”

Ingrid married Carl Orth and took that name. In 1904 she bought 160 acres in Fargo, Oklahoma. By 1915 she rented the farm out and headed back to Kansas. She lived there until her death on September 3, 1933.

Gustaf Magnusson left Sweden on March 25, 1887. He sailed from Malmo and the reason was simple – he wanted to avoid the Swedish draft. He paid 164 kr to travel to New York on the wooden schooner Ceres, a ship that had been built in 1859.

He made it to Kansas and worked in the salt mines for three years, taking English classes at night. He eventually got married – to a woman he often walked 28 miles to see – and they moved to Oklahoma. There was a sod home on 160 acres and the first year Gustaf brought in kafir corn, the second broom corn, and the third year wheat.

Gustaf died in Billings. He’d been taking a bus up to Montana to visit his sister and two brothers when he became ill and went to the hospital. Something happened and Gustaf was stabbed multiple times while a patient there. It’s unknown what happened, but that led to his death in July 1945.

The Strandberg Family Leaves Sweden

The trip from Sweden was pretty standard. Those leaving the country usually did so from Gothenburg, taking a steerage ticket most likely, which would cost 105 kr in 1880, or $1.14. (105 crowns is $28 today)

It was very hard to save up this money, as the average yearly earnings for a Swedish farmer in the 1880s was 138 kr, or $1.50. The good news is that room and board were typically included with this.

People would first head across the North Sea to England, usually the city of Hull. From there it was an immigrant train to the docks in Liverpool, 126 miles across the country. Passengers were expected to furnish their own food for this whole leg of the journey.

After that it was aboard ship for twelve days to New York and then it’d be on another immigrant train to Chicago. The train ride took five days and there were interpreters for passengers, something that likely helped on meal stops.

My family came over before Ellis Island was the main point of entry. They were processed at Castle Garden, but before getting off the boat they and all other passengers had to tear up their mattresses and throw them overboard, as well as provide the keys to their trunks.

Why did they leave Sweden? At that time the family owned just a quarter of a mantal of land. Stranghult had been reduced in size and may have been inadequate for a family of their size.

While coming over on the boat from Liverpool the parents were adamant that they were going not because of financial reasons but to keep the family together. Considering they travelled first class and not the more common steerage, there’s validity in this, although they’d just sold the farm as well, so that could be the reason for their sound finances.

Whatever the reason, they were moving, and not all were happy. Hilda Germundson wanted to stay back in Sweden with her true love. The family insisted she come to America, however, and she obeyed. Upon arrival the family discovered that she was pregnant.

It’s not known if Hilda knew this before leaving Sweden or not, though she would have been about 6 to 8 weeks pregnant at the time, so it’s likely.

By the time the child was due the family had reached Hutchinson, Kansas. The childbirth was difficult and both Hilda and the young baby died on October 12, 1891.

Hilda was just 20 years old. Magnus later said that if he’d known she was pregnant he “would have brought the young man along with the family.”

Whether it would have made a difference is unknown. It likely would have made Hilda’s time in America better, and perhaps that would have been the psychological boost she’d needed to get through the childbirth. The cause of death was listed as “heart trouble.” Sadly, it wouldn’t be the first tragedy that befell the family while in Kansas.

Two years after Hilda died her mother followed. Perhaps it was the untimely death of her daughter, or the strange new land she called home. Whatever the case, Teodora Magnusson died in October 1893.

The family settled into farming, primarily at a place called Pretty Prairie. They rented their land and moved about a bit. They also changed their name to “Strandberg.”

Where does the name “Strandberg” come from? Here’s the common telling:

“It is uncertain where the name Strandberg comes from. Gertrude Strandberg Peterson told of its coming from the farm Stranghult. In Sweden the name is a military name, and translates or means ‘shore mountain.’ Hardie Strandberg remembered his father Nils telling him it came from a railroad siding in Kansas. There is a railroad siding at the end of Swede Road in rural Reno County, Kansas with the name of Strandberg. We could not definitely assign a positive reason for the choice of names.”

Nils Strandberg and the Modern Montana Strandbergs

“Peter was one of the most fascinating men she had known. A hyperactive in all likelihood, he slept for 3 or 4 hours a night. Read his Bible often and was very proud of his Masonic 32nd degree. He had great knowledge of the stars and Viking Mythology, a grace and balance of movement. He started his children on gymnastics early in life.”

Peter would die on July 18, 1932, from injuries he received while repairing his tractor.

Nils Strandberg was born on March 10, 1879, and was the 8th child of Magnus and Theodora Germundson. He left Sweden with the family in 1891. He likely would have stayed in Kansas had he not had a brief and tumultuous love affair with the 21-year old Ada Gillett in 1900. He’d been working as a laborer on her mother’s farm, and their tryst likely didn’t sit well with the family.

There wasn’t much reason for Nils to stay as his father Magnus had died on November 30, 1901. Nils hopped on a train for Montana in early-1902 and was soon working on a ranch outside Helena and then later the gold mines. He got caved-in on several times and also developed lung problems. Still, the work was so good that in October he headed back to Kansas to get his brother Henry.

Nils stayed in the mines until 1907 “when a doctor told his brother to get him out of that kind of work or he wouldn’t live another year.”

It was easy to get out as Nils and his brother had started a small ranch in Canyon Creek in 1904. They also “batched” on the “Greaser place” and the “Geir place.” They also leased excess land to the Gans and Klein Company, on what is known as today’s Settle Ranch.

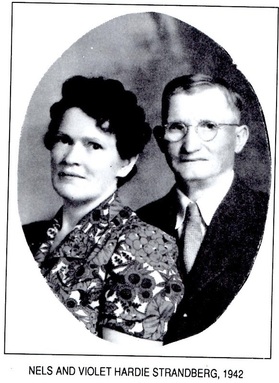

In 1916 Nils married Violet Hardie of Helena. They would have five children between 1917 and 1926.

Each of the brothers had $100,000 in cash and their banker advised them to buy up as many head of cattle as they could. They did, and had a lot of money in those fields north of Helena come the winter of 1919. The following summer, however, was hot and dry.

It looked like the brothers might be able to make it if they could just get the crop in. Before that could happen “hail came and took everything.” The brothers were broke and had no way to feed their cows. Nils was heard to say he wished the animals would go drown themselves in the lake, so heartrending were the starving animals’ cries for food.

The brothers lost everything, but they didn’t give up. Nils moved up to the Taylor Ranch, or what’s today’s Charlie Vulk ranch. That lasted two years before he moved on to the Opheim ranch, which eventually became Allen Shumate’s ranch.

It was there that Nils Strandberg ran the dairy business of Montana Savings Bank, milking 125 head of Holstein Freisen cows. At that point in time the Opheim ranch was managed by Thomas Marlow, C.A. Broadwater’s nephew.

Nils was never able to get back into business for himself. Perhaps he didn’t want to after the horrendous losses of 1920. He continued to help out area farms and ranches in the Prickly Pear Valley, such as the “Picotte place for a year” and then “north of Glass Drive” for ten years.

The latter was Michels and Synness land, which would come to be owned by Dick Wolstein. Also during this time Nils drove the school bus for Helena’s School District 30, a job he held from 1925 to 1930.

By the 1930s economic hard times were had by all, and the brothers decided to start a dairy business in the Helena Valley. By 1933 Nils had enough money to buy up 230 acres “of good irrigated land” there. He continued to work the land until heart trouble forced him to retire.

He settled into his home at 6145 North Montana Avenue. He died there on November 9, 1954. Nils’s brother Henry died in 1969, likely from lung problems brought on from smoking.

Nils’s wife Violet Strandberg lived on in the North Montana Avenue home until April 20, 1987. The home is now a church, the Mountain Fellowship.

That last saw it come back to the family, Albert Astrom. His son Ole’ Astrom bought it in 1956 and the farm saw the wooden house replaced with a brick house in 1962. The barn still remains, or at least had been there in 1977.

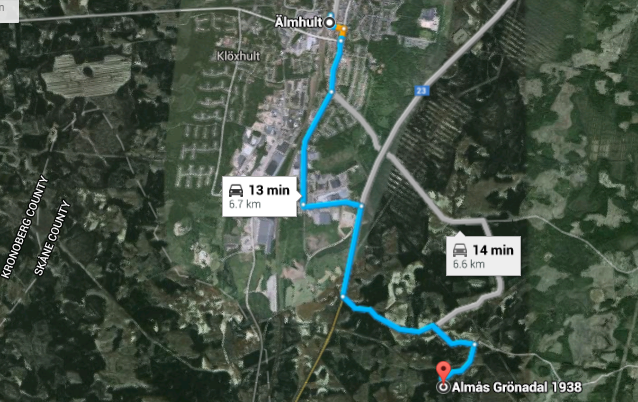

Stranghult is 2.4 miles south of the town of Almhult, then 3 miles east on a side road, then another 1.8 miles down a country lane to the main house.

Looking at Google Maps, this is about where I think the general area for Stranghult is.

Conclusion

He had no doubt they were “hard working, highly respected, and devout Christian people,” for “without exception” the clergy “wrote nice things praising our family.”

Strandbergs could read and write as early as the 1600s. Even though “during the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries people died young,” Strandbergs would “live into their seventies and eighties.” When death did come it was usually due to “chest illness” or old age.”

Strandbergs epitomized the Smålandian work ethic and brought it to Montana with them. The state has been better for it.