Petroleum County, pop. 494 (click for stats)

Petroleum County, pop. 494 (click for stats)

It’s not that they created the counties themselves, per se, but more that they convinced the legislature to do that for them. It’s no surprise, really, as having a county where you lived ensured you’d have roads, more services, better jobs, and closer access to government. The legislature obliged by passing the Leighton Act in 1915, which allowed counties to split themselves.

“Passed in an irresponsible moment,” historian Michael P. Malone writes, “the Leighton Act gave counties an almost completely free hand to subdivide as hey saw fit. They did.” (Malone, p 252)

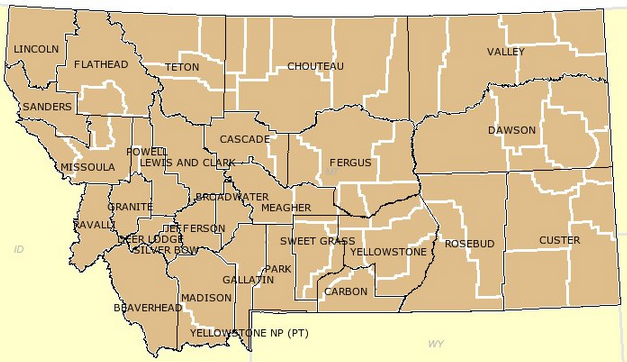

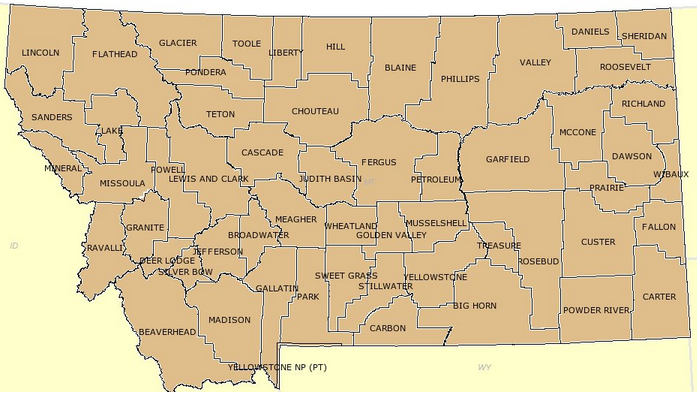

In 1910, prior to the Leighton Act, there were just nine counties covering the vast swath that would see the majority of the homesteaders. By 1925 there would be twenty-eight new counties, for our current number of fifty-six.

The main proponent of county splitting was Dan McKay, a “gaunt and unkempt and unlettered Scot” according to Joseph Kinsey Howard, who took to horseback and travelled around the state, talking to anyone who’d listen of the virtues of a state with many counties over one with but a few.

McKay thought creating new counties was good for the following reasons, which were listed in the Great Falls Daily Tribune in January, 1919:

“The matter of assessment totals, nature and development of the county involved, distances from present county seats serving the people affected, facilities for communication with other points, opportunity for development by reason of the creation of a new county, and some other factors all enter into my judgment as to when it would be wise to create a new county.” (Great Falls Tribune, January 2, 1919)

He seemed tame as he rode around on his horse in the early 1910s, but he’d bring disaster in his wake. He had a folksy manner, one that drew people in. “He was crude and coarse and his grammar left much to be desired,” writes Joseph Kinsey Howard in Montana: High, Wide, and Handsome, which meant his language “was that of his listeners, and any smart aleck who heckled him about his shortcomings was soon put in his place.” (Howard, p 236).

“gave him a sense of power and everybody knew his name – a name cursed and cheered in the newspapers, on street corners, in the wheat fields and in the legislature. Dan was happy because he loved fame, he loved to talk, and he loved to ride his big horse.” (Howard, 237)

The farmers weren’t hard to convince.

- First, they were surrounded by a whole lot of nothing, empty land as far as they eye could see in most cases. The idea of having a county seat a little closer no doubt filled them with some hope and encouragement.

- Next, Dan McKay and his men assured everyone who’d listen that having that extra government presence in their lives would be a good thing. There’d be new government positions, which meant more payroll, and thus more money for local businesses. This was a growth potential!

Still, it wasn’t easy convincing everyone, and in his later years McKay likened county splitting to war:

“If you never had the thrill of the hardest kind of a battle that can be fought without artillery, rifles and machine guns, you ought to get into a county splitting fight once. It will give you plenty of thrills.” (Great Falls Tribune, January 28, 1936).

Dan McKay thought so, but then Dan McKay didn’t see a huge drought and agricultural crisis right on the horizon. But then no one did, except the soil scientists that James J. Hill was doing his best to drown out. But even if that drought never would’ve came, there was still no logical reason for Montana to create so many more counties beginning in 1912, as the history of Montana’s counties shows.

Forming Montana’s 56 Counties

In 1865 the counties of Big Horn (renamed Custer in 1877), and Dawson counties were created. In 1867 Meager County was added and then ten years would go by before the legislature felt another needed to be added, Custer in 1877.

The 1880s saw six new counties created, primarily because the population there was growing. These were Silver Bow in 1881; Yellowstone in 1883; Fergus and Sweet Grass in 1885; and Cascade and Park in 1887.

The 1890s saw just six counties as well, Flathead, Granite, Ravalli, Teton, and Valley in 1893; and Carbon County in 1895.

In the 1900s there was Powell and Rosebud in 1901; Sanders in 1905; and Lincoln in 1909, forty-five years after President Abraham Lincoln signed the law making Montana a state. Forty-five years isn’t that long of a time in Montana, and it’s likely some in the state were blustering about that decision by the legislature.

It was in the 1910s that counties really multiplied in the state, primarily because of Dan McKay and the many men he had helping him collect petition signatures for new counties to be created, all at a small fee of course.

In 1911 Musselshell County was created and then in 1912 Blaine and Hill Counties were added. That was the year of the Leighton Act, and the floodgates opened wide.

In 1913 Big Horn, Fallon, Sheridan, and Stillwater were created. In 1914 Mineral, Richland, Toole, and Wibaux came into being. In 1915 Phillips and Prairie were added and in 1917 Carter and Wheatland joined the rosters. The final year was 1919 when Garfield, Glacier, McCone, Pondera, Powder River, Roosevelt, and Treasure counties were created. After that the state rested, nineteen new counties in seven years.

By 1920 Montana had fifty counties and she wasn’t done yet. In 1920 Daniels, Golden Valley, Judith Basin, and Liberty were added while in 1923 Lake was created. The final county created in Montana was Petroleum in 1925. At fifty-six counties, the state was finally divided all she could be.

When all those homesteaders headed back to wherever they’d come from, those counties and the new costs they demanded didn’t go with them, instead they stayed right here in Montana and their maintenance and upkeep was divided between all the other counties. It’s no surprise that a lot of the resentment the western portion of the state has for the eastern arose during this time.

What happened next is simply inexcusable, and set a terrible precedent for the state. When the bust set in many couldn’t pay the taxes on their property. This ensured that the move by the 1915 legislature would force county governments to seize private property through tax sales in order to pay their own bills, most of which came because of those new counties.

“Montana’s per capital tax levy, $26.83, was the highest in the United States when county splitting began in 1912,” Joseph Kinsey Howard writes. “Nine years later it had grown to $50 and taxes upon property had risen from 11 to 27 million dollars.” (Howard, p 240)

It was a vicious cycle that looked to have no end, and still it wasn’t enough – property taxes jumped 140%. Few could afford to own land anymore besides the county itself, and they had no money to pay taxes on it either.

Montana gained 23% more people from the time county splitting began to 1920, yet expenses also increased for the counties, a whopping 108%. What’s more, many counties simply couldn’t pay their bills, something that caused the interest rates on their debts to soar to 271%.

Schools weren’t much different. Despite an increase of just 42% in the number of students attending, school costs increased by 145%.

The counties got sucked into a downward spiral, one that saw their debts rise as they continued to borrow up to 5% of what the properties in their area were worth. In 1913 the state of Montana had thirty-three counties and together they were in debt to the tune of $16 million. By 1921 there were fifty-four counties, together owing $60 million, an increase of 375%.

Counties don’t pay taxes to themselves, and that put the state further into debt on the up to $30 million in taxes it couldn’t collect. Property values simply plummeted in response, and by 1925 Montana farms lost $320 million in value. And this was at a time when the citizens of the state had given 42% of their earnings back to the state in the form of taxes. There was little to show for it but dusty towns and empty fields, both ready to blow away in rising winds.

Dan McKay lived to see the problems the counties ran into, counties he’d done so much to create. Budget deficits, property seizures, property value losses…all manner of problems that came from it were witnessed by him for a decade or more after they came about. But he always had that big horse to ride around on, and everyone knew his name. Dan McKay died in his home in Glasgow on January 27, 1936. He was 80 years old.