Anyways, I got this nice email from Amanda Curtis today:

America loves rematches, just look at the Rocky film franchise, which I profiled in my book SEO & 80s Movies. Those puppies made bank, and they still make bank. Why? Because people like seeing people beat the shit out of each other, and then come back for more.

It’s the American way, plain and simple. Or could there be an insurgent effort to supplant the…well, I should probably just stop there – sometimes just letting you use your imagination is more fun.

Regardless, I think we’ll see more of Curtis and no one’s disputing that. But what about until then? I’m guessing it’s back to the classroom, maybe some substitute teaching gigs unless they’ve got an open spot somewhere in a district.

Does she really want to shuttle back and forth again from Butte to Helena after driving all over the damn state this fall? Shit. Eric Feaver should be able to help her out, don’t you think?

Well, what else is there? Ah, returns. Let’s look at some historic returns while the political scientists are busy in class or doing whatever.

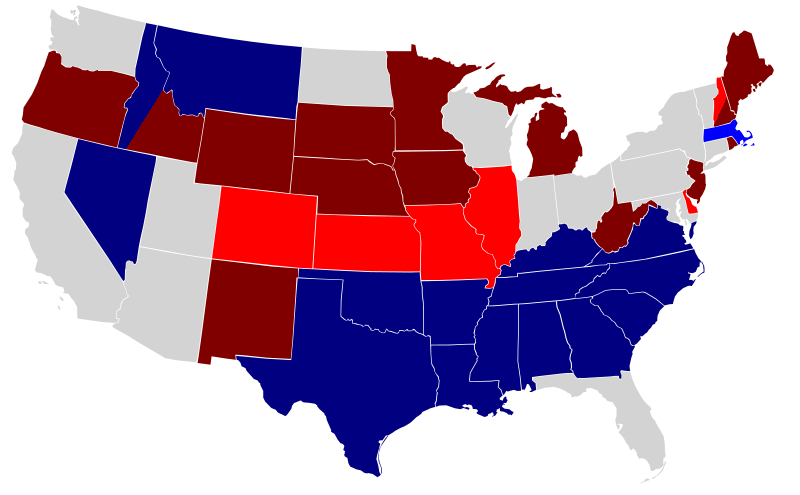

The Election of 1918

That vote may have come back to haunt Rankin when she ran against Walsh in the 1918 election. The year 1918 was the first that would see an election in a time of war since the Civil War fifty-four years earlier – no one much counted the Philippine-American War as anything. Voters were weary of fighting, especially with death tolls beginning to filter back from Europe.

Instead of trying to run for her seat again, she switched over to the U.S. Senate race, going for Democratic-incumbent Senator Thomas J. Walsh’s seat. She lost in the primary to Oscar M. Lanstrum, 18,805 votes 17,091 votes, with two others taking more than 9,000 votes between them.

The general election in November was an identical matchup, pitting her against Senator Walsh and her nemesis in the primary, Oscar M. Lanstrum. It wasn’t even close for Rankin, with Walsh taking 46,160 votes over Lanstrum’s 40,229 to keep his seat. Rankin got just 26,013 votes, or 23% compared to Walsh’s 41% and Lanstrum’s 35%.

Jeanette Rankin had only served until March 3 of that year and then headed back to Montana. The defeat must have hurt, doubly so since the gap between her and Lanstrum had been so wide. Montana, it seemed, was not ready to send another third-party candidate to Washington like they had in 1900 with Caldwell Edwards.

Rankin went off to Georgia the next year and began organizing social clubs for children while advocating pacifism. Her brother Wellington would stay in Montana and continue to have a hand in Republican politics. Neither of their stories was even close to being finished.

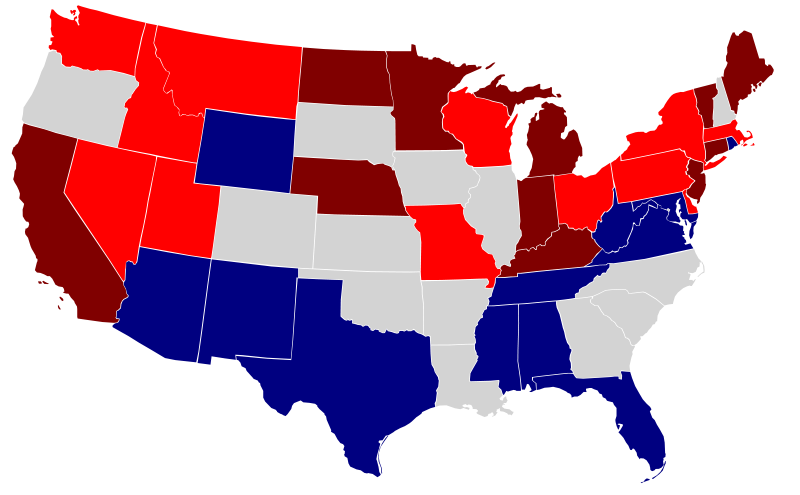

The 1946 Election in Montana

Henry L. Myers had held William A Clark’s old seat (the one Paris Gibson took over) from 1911 to 1923. After that it was Burton K. Wheeler’s for more than twenty years. He was sitting nice, but the question is, did he see the change coming? Did anyone?

Democrats had been in charge in Congress since 1933 when they took over in the landslide election that put FDR into office right as the Great Depression was getting going. To many in 1946 it seemed another depression was going, this one primarily centered around the White House, where Truman’s approval rating was a dismal 32%.

Breaking up striking auto workers and miners didn’t endear him to many, and when those price controls that WWII had put in place came to an end, whoa boy, a lot of people were angry.

The same had hit the Democrats in 1920 when the WWI price controls ended, and Republicans swept into the White House, Harding taking more than 60% of the vote.

Zales Ecton was just 22 years old when that happened, and probably making his way through the University of Chicago Law School. His family had moved to Gallatin County when he was but 9, from Iowa, and in 1921 he returned to become a rancher.

Democrats were thinking the same thing, and Montana Supreme Court Justice Leif Erickson chose to challenge Wheeler in the July 16 Primary. No doubt he ruffled some feathers of the party established, but he pulled of an upset, and it wasn’t even close – 49,419 votes to 44,513, or 52% to 47%.

Low turnout was probably a factor. In the 1946 Montana primary election, 241,550 people were registered to vote, yet only 127,889 of them actually bothered doing so, or 52.9%.

That fall things improved, and markedly so. There were now 263,422 people registered to vote and 190,566 of them did so, a whopping 72.3%.

For the Democrats, that was bad. Erickson managed only 86,476 votes to Ecton’s 101,901. For the first time since 1923 a Republican would be filling that Senate seat, and doing so with a margin of 54% to 45%.

But that’s a story for another day.

Notes

1946 Montana Primary Results

Historic Voter Turnout in Montana

Erickson and Court Packing

Info on 1946 Midterms and 1928 Election