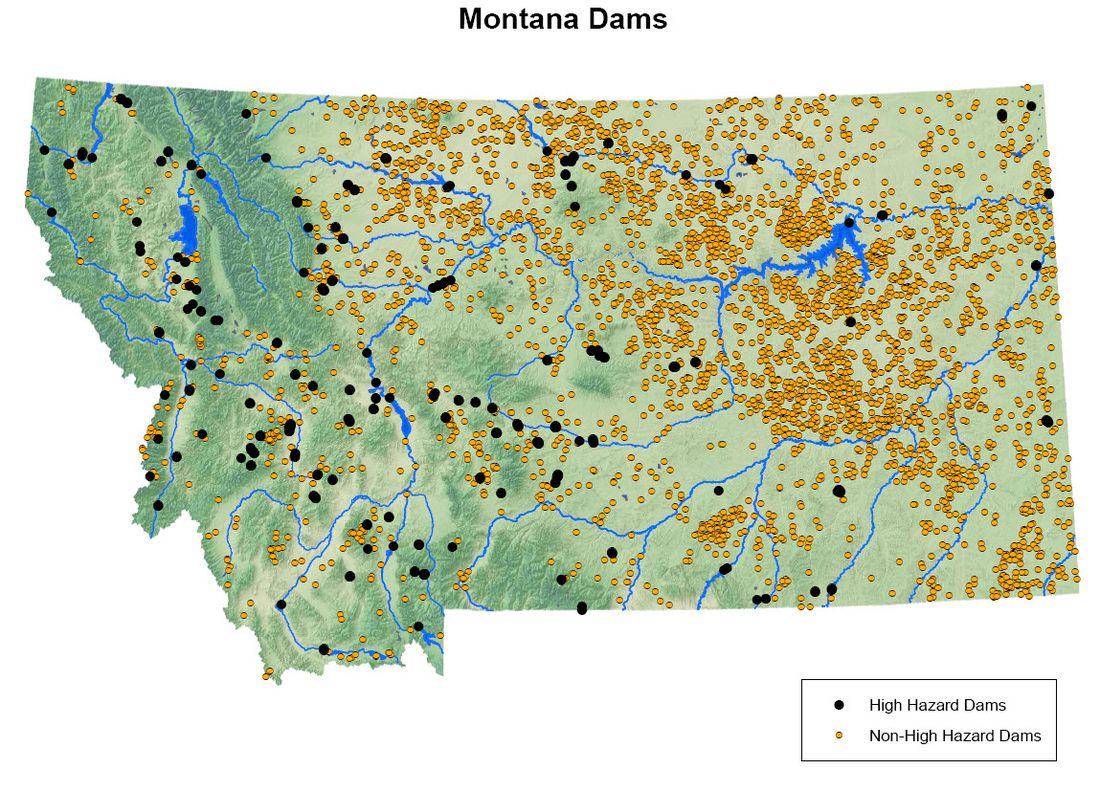

What’s more, there are 186 dams that are currently listed as ‘high hazard,’ or with the serious potential for loss of life further downstream should any kind of serious incident occur.

Together, however, these dams served a duel-function – to provide water to the homesteaders flocking to the state and power to growing corporate industries that dominated it. Two side effects of this were electricity for consumers and new recreational opportunities. Both would create problems and opportunities for Montana as the 20th century progressed.

The 1902 Reclamation Act

Before these had been ignored, with wiser heads realizing they weren’t sustainable long-term through the periods of wet and dry that comprised Montana’s weather and agricultural cycle.

One of the problems was that researchers just didn’t have the facts and figures to back up their opinions – records just hadn’t been kept that long. The other was that many got swept up in the idea of easy money that a homesteading boom would bring.

Coupled with that idea was the promise of free electricity, once dams had been built. The potential for profits was immense, and many men got sucked into it, none more so than former territorial governor, Samuel T. Hauser. Hauser saw the potential that hydropower had to create wealth, something he badly needed after his finances were hit hard in the Panic of 1893.

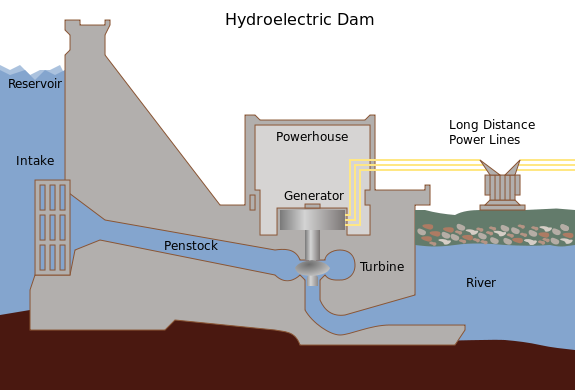

How a Dam Works

Most of the time engineers built turbines at a low elevation on a river that already had a natural drop. That gravity saved money by doing most of the work, and letting that water fall onto the penstocks through an intake valve that can be controlled by dam operators. The water rushing into the intake then goes into the penstocks and hits the turbine, often spinning a propeller so it moves.

Tales of the 1860s gold rushes and 1880s copper bonanzas in Butte were still fresh in the minds of those that’d heard them as children instead, and they felt it was now their time to cash in on a Montana boom. Hydropower seemed a great way to do that, especially after the example of Montana’s first dam, the Black Eagle Dam. One monumental dam proposed for the state was the Gibson Dam, which was part of the larger Sun River Project.

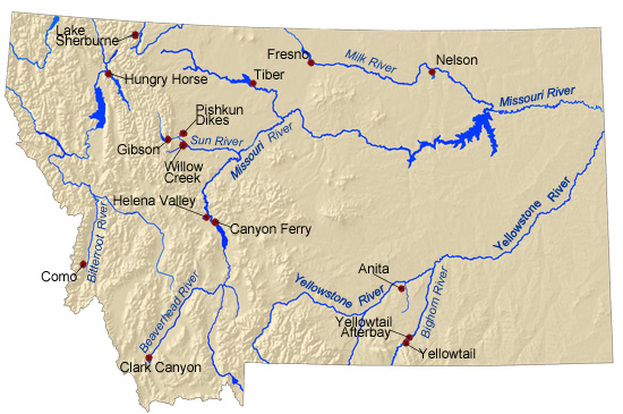

The Sun River Project

The Sun River had originally been called the Medicine River by the Blackfeet that had first lived around it, and it flows out from the mountains of the Continental Divide for 130 miles before reaching the Missouri River at Great Falls.

It all started on September 26, 1906, when the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s Sun River Project was approved by the Department of the Interior. Surveyor Herbert Wilson was an early proponent of the projects centerpiece, the Gibson Dam, having identified the site in 1889.

It wasn’t until 1911 and the growing farming craze taking place in Montana that the Bureau of Reclamation got serious and commissioned studies based on Wilson’s findings, which were finally implemented into a dam plan by 1920.

To make such a large project more manageable, the government divided it into two smaller irrigation districts – the 81,000-acre Greenfields Division to the north of the river and the 10,000-acre Fort Shaw Division to its south, which was later expanded to another 3,000-acre capacity.

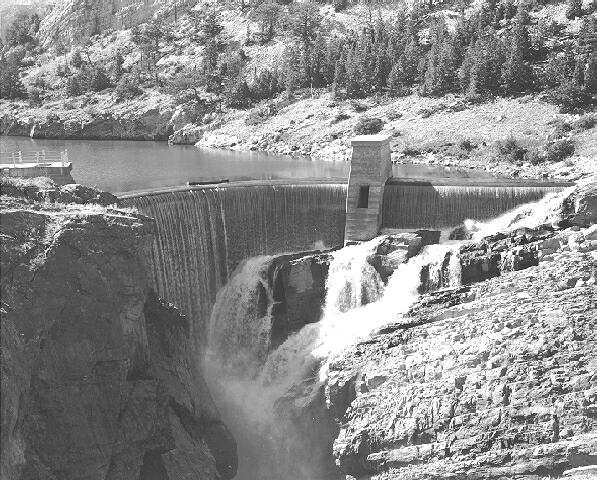

The Gibson Dam would be built to get all that water to where it needed to be, but the infrastructure the dam would feed was built first, starting with the Willow Creek Dam, which started in 1907 and finished in 1911 in Lewis and Clark County near Helena and was one of the first pieces of the larger Sun River Project. The dam comes in at 93 feet high and 650 feet long and creates no electricity, instead forming the Willow Creek Reservoir upon for irrigation.

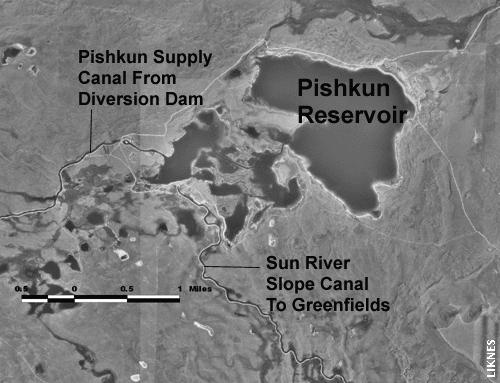

In addition to getting water directly from the dam, Willow Creek Reservoir also gets water from the Willow Creek Feeder Canal, a 7-mile route that feeds water from the Pishkun Supply Canal at a rate of 125 cubic feet per second, although if it wasn’t for erosion issues it could move up to 500 cubic feet per second.

The Pishkun Supply Canal was a larger part of the Greenfields Canal System, which was built beginning in 1913 and took seven years to finish. The heart of the multi-canal system is a 39-mile long canal that heads towards Fairfield. To ease the water’s passage there are several drop structures, or small waterfalls that allow the canal to slope. When the water needs to be filtered-off to an adjacent area ‘turnouts’ are used.

The whole Greenfields Canal System was completed in 1920 and water was made available to homesteaders that very same year. The wider distribution system that extended for miles in all directions wasn’t entirely finished until 1936, however, and complete drainage canals didn’t come in until 1958.

Additional water is able to get to the north of the Sun River through a quarter-mile and 1,400 cubic feet per second capacity tunnel that moves under the roadway and feeds into the Pishkun Supply Canal as it makes its way to the Pishkun Reservoir.

While the Sun River Diversion Dam and Greenfields Canal system were being built, the Pishkun Reservoir was also started, beginning in 1914, and 15 miles from the proposed Gibson Dam site. The reservoir can hold 46,700 acre-feet of water but just over 32,000 acre-feet of that is able to get out of the dam each year. That much water takes up 1,550 surface acres and creates 13 miles of shoreline. It flows into the Piskhun Reservoir at a rate of 1,400 cubic feet per second and flows out at 1,600 cubic feet per second.

Another piece of the Sun River Project is the Fort Shaw Irrigation District, which began construction in 1907 and saw most work done by 1908.

The main component is the Fort Shaw Diversion Dam, which is a rockfill structure measuring 400 feet wide with a drop of 9 feet. Two cast-iron and automated gates allow 225 cubic feet of water per second to spill over the dam and head into the 12 miles of canals that in turn feed 85 miles worth of lateral canals to water 10,000 acres of farmland.

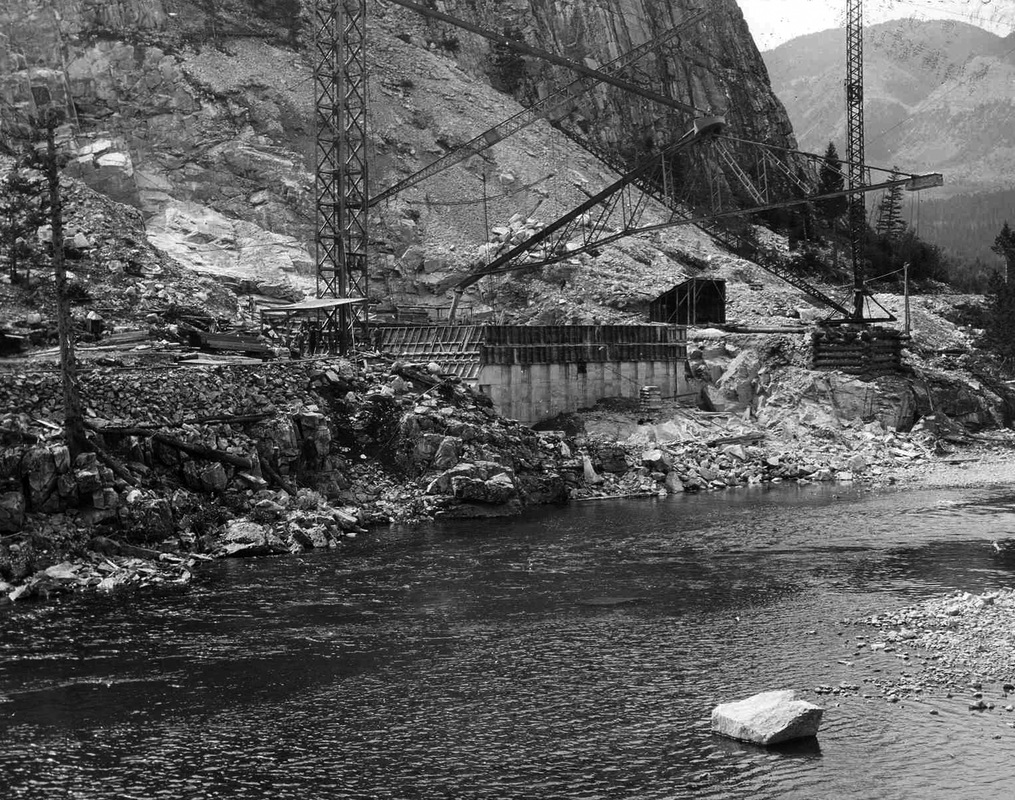

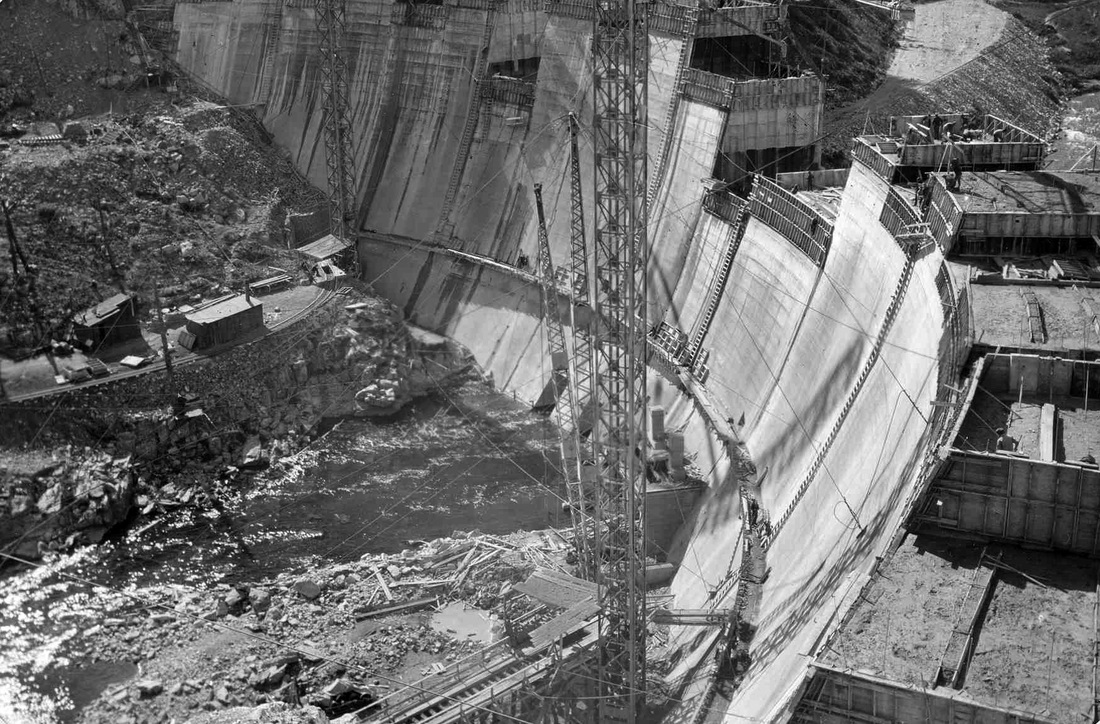

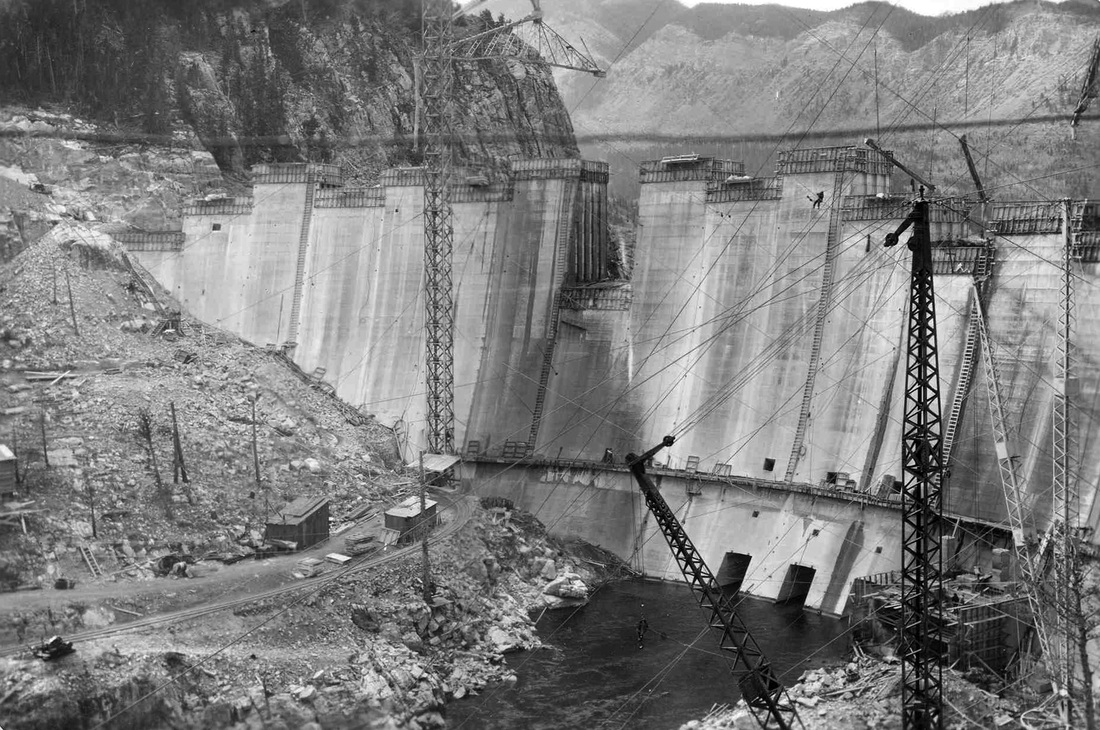

The Gibson Dam

During the dam’s construction superintendant Albert E. Paddock died when a worker fell 60 feet and hit him, causing the latter’s death as well.

Subsequent studies have suggested the dam could produce 15 MW if a powerhouse making use of the original penstocks were built near the dam.

Instead the dam would be used solely for irrigation, filling each year with the spring runoff from the surrounding mountains and then being drained in the crucial summer months when the crops needed so much water and the clouds often gave too little.

Thus the Gibson Reservoir was born, which has a shoreline measuring 15 miles covering 1,296 acres and can hold up to 96,477 acre-feet of water. Some places in the lake reach 195 feet deep.

To build such a massive thing workmen had to first construct eight earthen dikes, each 9,050 feet long and ranging between 10 and 50 feet high. The dam was designed using the trial-load method of mathematical equations to determine where the most stress and strain on the dam will be.

One thing is for certain – it certainly got rid of a lot of the stress farmers in the area had been feeling before the massive dam and irrigation project were put in.