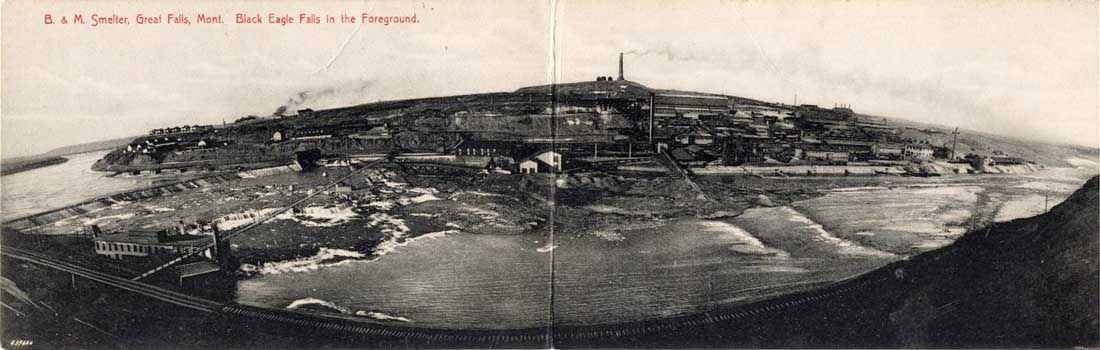

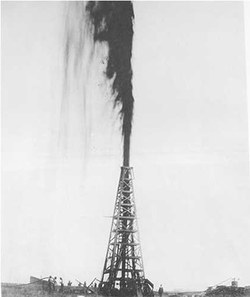

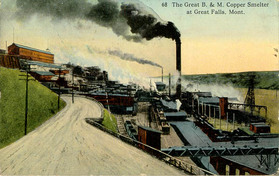

A view of the B&M Smelter in Black Eagle

A view of the B&M Smelter in Black Eagle

Well, what they really wanted to know about were the bars there.

Those bars had their heyday around WWII, though the community that housed them had seen its heyday come and go long before that.

Let’s talk about Black Eagle today, and it’s long and interesting history.

The Early Communities that Became Black Eagle

This was a few years after the town of Great Falls started.

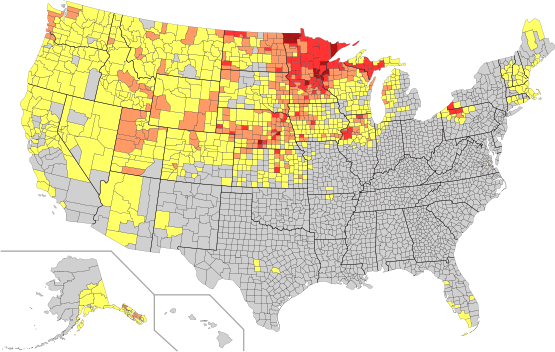

Ads were put out in national newspapers for copper workers to come.

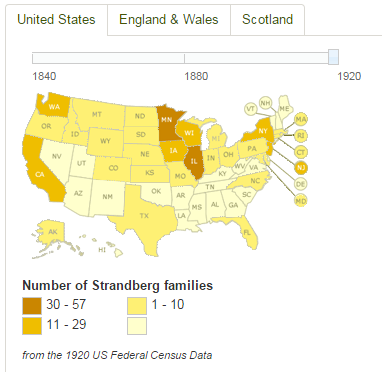

Calumet, Michigan, supplied many of those workers and soon Little Milwaukee rose up east of the smelter.

The residents were largely Italian and Croatian, with a good mix of Yugoslavians, Czechoslovakians, Greeks and Norwegians thrown in too.

Around 200 people eventually settled there, though there were as many as 500 shacks at one point.

Little Milwaukee lasted until 1903 when company officials ordered the families off the land. They moved to Little Chicago.

The main reason for the move was because of the smelter expansion, but also because “rail magnate James Hill was appalled by the sight of the shanty town.”

North Great Falls

A new community called North Great Falls soon developed 200 yards north of the Anaconda wire mill as well. About 150 people lived there in the 1890s, working for the B&M Smelter.

“It was not uncommon for the breadwinner to work at least 10 hours a day, seven days a week, for $2.50 a shift. However, it must be remembered work shoes sold for $2 a pair or less, overalls, 40 cents a pair; bread 5 cents a loaf, and beef, as low as 5 cents a pound.”

One famous resident of North Great Falls was Alex Remneas, “an outstanding baseball pitcher” in the early-1900s.

Residents of North Great Falls had to cross the Missouri using the First Avenue North toll bridge. Then the 15th Street Bridge was built in 1892 and the community began to move away.

In 1895 and 1896 there were several fires that destroyed homes. By 1906 there was nothing left of North Great Falls except for a few shacks.

Black Eagle is Chosen

It was the first hydroelectric dam on the Upper Missouri River, and this video has a good history of it.

By 1916 the whole area was renamed Black Eagle when postmaster August Cor added a post office to his small grocery store located at 1517 Smelter Avenue.

No licenses were required to start a business in Black Eagle, and that’s how most of the bars started up.

There was an Irish saloon, a Swedish saloon, an Italian saloon, and a German saloon, as well as Malmberg saloon and Johnson’s saloon. The 40-room Flatiron Hotel also had a saloon, though the building was destroyed in 1900.

The people of Black Eagle lived simply in shanty-like houses with no running water or sewers. “Most homes tossed their wastewater into their yard or in the street.” Even as late as the 1920s water was drawn directly from the river, and came out “soupy.”

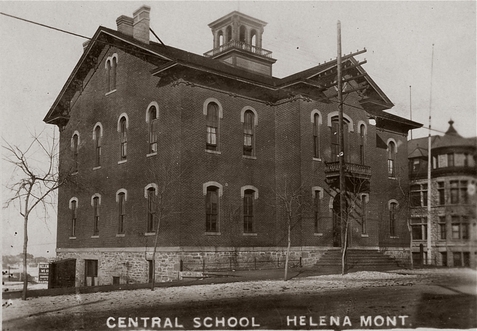

Black Eagle’s Schools

The new school was built that same year and renamed Copper Smelter School until sometime in the 1940s when the name changed to Collins School.

The name came from Fannie B. Collins, who worked at the school as a teacher and principal from 1909 to 1942.

She made $902.50 a year to run the school, with four other teachers helping. The teachers made between $740 and $900 a year.

Miss Collins taught the children of Anaconda Company employees, “smelter workers and big bosses alike.”

Amelia Polich, a first-grader in 1909, remembered that unruly children would go home at noon and line their pants with shingles, the better to ease the spankings their parents would give for such behavior.

Another student remembered that the nearby brick yard was very loud from the sound of dropping bricks. When a kid in class was asked a question they’d sometimes “wait for the bricks to drop – the noise gave him a little more time to come up with an answer.”

Collins School lasted until 1979 when it was closed as a cost-savings measure by the Great Falls school board. Declining enrollments and rising costs were the main reason.

Black Eagle’s Bar Troubles

A big problem at that time were underage drinkers and how late the bars stayed open.

The Miami Café got into trouble for selling liquor after 2 AM and was denied their liquor license renewal sometime in the 1940s.

On December 26 (I don’t know the year as the newspaper clippings had none), Great Falls high school athlete Bud Kirwin charged that military police had attacked him in the Black Eagle night club without provocation. The military prepared court martial proceedings against two soldiers.

Supposedly Kirwin told the two MPs that “another boy at the bar was not a soldier,” whereupon they “slapped Kirwan several times, and when Kirwan was removing his coat the soldier clubbed him with his gun.”

There was a big problem at the time with minors going to the nightclub, so law enforcement officials were often on-edge.

Shortly after this a “mass-meeting of Black Eagle residents” was held to discuss “plans to curb and stop the growing unbearable nuisance caused at night by some undesirables from Great Falls.”

One of the main proponents of cleaning up the town was Black Eagle’s mayor, Ed Shields. He decried “a few beer hall owners or operators who were not patriotic enough “to close down at midnight, as Malmstrom’s General Dewitt wanted.

A big problem was how Black Eagle was looked down upon by the military men from Great Falls.

“For many years past the residents of Black Eagle have keenly suffered under gibes relative to their national origin, insults as to their mental capacity, etc., until today they have become utterly sick and annoyed at these uncalled for and un-American taunts.”

At that point residents had been trying to institute earlier closing times for the bars for 8 to 10 years, with no help from local or state authorities.

Conclusion

Most pertain to the early days, with the rest talking about the 2010 superfund listing.

“Streets were muddy and many alleys contained piles of manure,” back in Black Eagle’s early days as a smelter town, but the real problems couldn’t be seen.

You could see the shit in the street, but what residents couldn’t see were the high levels of contamination they were living upon.

Between 1893 and 1980 copper smelting and metal refining created “elevated levels of lead and arsenic” in the soil of 375 homes, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency studies found in 2010. This was from the contaminants coming out of the 502-foot stack the refinery operated.

“Millions of tons of waste” were also dumped into the nearby Missouri River during this time. The EPA figured that “950,000 tons of slag and tailings were released in the river in 1907 alone.”

In 1977 Atlantic Richfield Co. bought up the site.

In 2010 it was designated an EPA Superfund cleanup site. Atlantic Richfield paid the EPA $1 million for cleanup. BNSF Railway Co. was also ordered to “investigate pollution in a railway bed in the community.”

We don’t get a lot in between the early days and the superfund days, but what we do know I’ve told you.

I hope this gives you a bigger picture of Montana and her history.

“Collins plans last ‘hurrah’ as it becomes a memory.” Great Falls Tribune. 1979.

Ecke, Richard. “Black Eagle listing advances: 60-day public comment period begins Thursday.” Great Falls Tribune. 3 March 2010.

“Highlights of history.” Great Falls Tribune. 12 June 1994.

Palagi, Guy. “North Great Falls’ Heydays Described by Ex-Sheriff.” Great Falls Tribune. 2 April 1967.

Polich, Rudy. “Town became Black Eagle – when it got a post office.” Montana Tribune. 25 March 1984.

Puckett, Karl. “’In the Shadow of the Big Stack’: Black Eagle group collects old memories.” Great Falls Tribune. 20 November 1997.