Bitterroot National Forest

Bitterroot National Forest

Let's look at some real numbers concerning Montana’s timber industry, not numbers that came out of a hat.

Speaking of Montana’s timber industry in the early 20th century, or from roughly 1900 to 1940, historian Michael P. Malone had this to say in his book Montana: A History of Two Centuries:

“By national standards, production was irregular and small. The slower-growing Rocky Mountain forests could not match the productive forests on the West Coat and in the South, and Montana output usually totaled only 250 to 400 million board feet per year.” (p 332)

In 1920 America produced 35 billion board feet. That was a huge increase from the 5 billion board feet that had been produced in 1850, but exactly the same as the 35 billion that was produced in 1900.

Things heated up in the Roaring Twenties and production grew to 39.7 billion board feet in 1926 and then began to fall off. By 1930 it was down to 26.1 billion and in 1934 America was spitting out just 12.8 billion board feet a year.

Profits didn’t follow the same trend. Numbers aren’t available for all years, but in 1926 the value of that production was $117 million, which was down from the $167 million of 1922. That fell to $110 million in 1930 and then rose to $202 million in 1932. The reduced supply was certainly driving up the price as the Depression wore on. A large part of this decline was companies shutting down, but it was also the rise of cement and steel products being used in place of wood.

Forestry is an industry that’s hard to pin down through the decades. In 1930 there are no detailed numbers for jobs, and in fact forestry’s lumped in with other areas. By 1940 we get some good numbers, but again, there are discrepancies. Two numbers that are the same in both instances where they’re reported are agriculture, forestry and fishing – non-manufacturing, with 146 people, and lumbermen, raftsmen and woodchoppers with 712 people. Altogether that gives us anywhere from 1,187 to 1,826 people working in the forestry and wood products industry in the 1940s in Montana, a difference of 639 people.

Still, forestry is an area that wasn’t a very large part of Montana’s economy. Even in 1930 it’d only been 1.38%, and that when it was combined with fishing. By 1950 there were only 838 sawmill laborers, according to the U.S. Census report for that year. Don't think that was the War, either - in 1940 there were just 914. In 1950 there were 865 lumbermen, raftsmen and wood choppers. In 1940 there were 712.

Montana’s Timber Industry, 1950 to 1980

Logs in Bonner

Logs in Bonner

Altogether that gives us 2,438 people in the forestry and wood products industry. Comparing percentages we see that from 1940 to 1950 the industry grew by more than 205%. Still, it didn’t employ anywhere near how many workers we like to think it did while looking back today, nor did it challenge other industries. After all, there were 3,057 waiters and waitresses in 1950. Then again, there were also 4,610 carpenters. This brings up another question, should they be counted too? After all, it’s a good bet much of the wood chopped in Montana was then used by other industries in Montana, such as carpentry. Should that figure into our calculations? For Malone I believe they do.

After the war Montana’s timber industry took off by all accounts. There was a building boom going on as Americans got their fair share of the American Dream. Home building across the nation took off and Montana was no different. There was a huge demand in timber, and Malone makes it clear what this meant:

“Montana’s forests of fir, spruce, and lodgepole and ponderosa pine, which had always been of generally marginal commercial value, began to attract more and more loggers. By 1948, there were 434 mills, most of them small, operating in the state. Employment in the wood products industry shot upward, to 5,374 in 1950 to 7,150 in 1955. The boom decreased during the late 1950s, and many of the smaller operators closed down. But by then, big-time investors had begun to develop a truly diversified wood products industry in Montana.” (p 333)

The surrounding timber operations benefited as the company stabilized the ups and downs of their operations with a steady stream of work. It was an economic success, but an environmental step back. With those jobs also came an immense amount of air pollution from the operations.

By 1969 the mill had undergone its second strike, the first lasting 11 hours the second two weeks. This resulted in pay going from $3.67 an hour to $4 an hour. “Hoerner-Waldorf’s pulp and paper enterprise brought hundreds of new jobs to the Missoula area,” Malone writes, “and helped make that city the Montana boomtown of the 1960s.”

Timber in Montana in the 1960s was centered around western Montana, particularly Missoula and Libby, though Christmas tree farms grew up around the Flathead and pole cutting operations grew up around various areas of the state. The industry expanded and diversified, but it wasn’t enough to help it weather the storms to come.

Montana’s timber had always been considered sub-par commercially, and the boom cycle of the 1950s finally went bust in 1970. In 1968 just 1.5 million board feet were produced in the state. There were small gains in 1983-4 in Montana and the country, but that typically came with consolidations as the industry became more automated and less manpower-driven. It was the story of the mines all over again.

The Montana Timber Industry, 1980 to 2011

“Perhaps more than any of Montana’s other extractive industries, it is extremely vulnerable, not only to foreign competition, particularly from British Columbia, but also to problems of supply. Environmentalists and wilderness advocates have heavily criticized clear-cutting and below-cost timber sales on National forest lands. As those groups have gained nationwide support, lumbermen have found that they are less able to secure adequate supplies of wood for their mills.” (p 334)

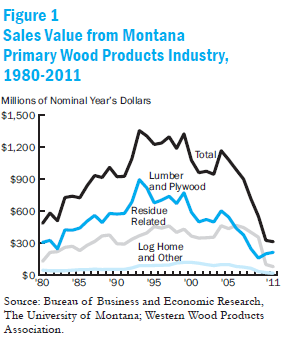

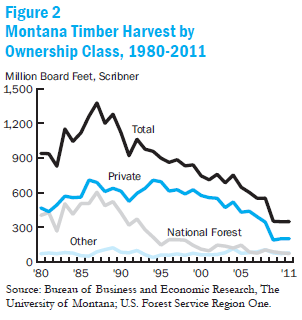

Timber harvests in Montana of course reacted accordingly. In the early 1980s the state was putting out just over 900 million board feet a year. By the mid-1990s that rose to over 1.2 billion board feet but then fell off to about 348 million by 2011. Those are the lowest harvest levels since 1945.

What is causing this? The lack of demand is a big one. The closure of the Smurfit-Stone Container Corp. was a hit. And then there’s federal lands, which many think will help. The problem is that they supply just a quarter of the mill lumber. By the 1990s, the federal government owned 12 million of Montana’s 17.3 million acres of forestland, but that’s how people want it.

So we get back to construction starts, of which there were just 630,000 in 2011. For a time it looked like construction starts in China might help, but they want logs not lumber. So that brings us to our current situation, and it’s not really good…but for whom?

For Montana timbermen, it’s bad. But for our huge recreation and tourist industry, it’s good. We know tourism employs more, and when we get to the numbers, we’ll prove they earn more.

Or did you think that’s just a load of rubbish?

Fine, but before you visited this site, how much did you know of the state’s timber history?

Conclusion

Custer National Forest

Custer National Forest

That’s fine – Montana has a whole collection of dead industries that harken back to our pioneer days, or nation-building days, and the days we now look back on in shame. Timber isn’t Montana’s future, it’s its past.

Montana will become a tourist state. Nay, it already is, but what it must strive to become is a unionized tourist state. Montana isn’t California and it isn’t Florida. It’s not Idaho and it’s not Washington. When you come here you see things you won’t see anywhere else and memories are made that can’t be made anywhere else. That’s a price worth paying, and when you come to Montana, you will.

We care about our workers here, our 100,000+ strong tourism industry, the face of our tourist industry. Without the folks making beds and serving meals and guiding travelers, there’d be no tourism industry in this state. And never forget that they’re coming to see the trees still standing, not the fields where they once stood.

Montana’s timber industry has a long and proud history in the state, but it’s just that, and will remain forevermore, a history.