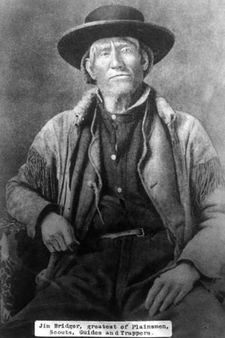

Jim Bridger

Jim Bridger Tragedy befell the family just four years after their move. In 1816 Bridger’s mother died, and his younger brother followed soon after. In 1817 his father died, leaving him and his sister as orphans. Jim started to operate a ferry for a time, and then moved to St. Louis and became apprenticed to a blacksmith. He worked at the forge until a newspaper advertisement caught his eye, and changed his life forever.

Joining the Fur Trade

Map of Green River

Map of Green River His beginnings as a mountain man were already off to a rocky start with the attack by and on the Arikaras, and it didn’t get better when he became involved with Hugh Glass and the grizzly. Bridger was one of the two men that had left Glass for dead after the bear had mauled him, and the decision weighed heavily on his conscious in the weeks before Glass reappeared from the dead one day at the gates of Fort Kiowa. Fearing he’d die still a young man, Bridger was relieved when Glass chose to forgive his youthful transgression as opposed to killing him.

Trapping and Exploring

Map of Great Salt Lake

Map of Great Salt Lake Over the next several years Jim Bridger would hone his skills as a fur trapper, mountain man, and explorer. He did well for himself, and was able to fight off the numerous Blackfeet that continually attacked him and his companions. He built up a loyal following of men, and a good amount of money as well.

When William H. Ashley decided to hang up his hat and retire from the fur trade in 1830, Bridger was one of the men that bought him out. He and his partners continued the Rocky Mountain Fur Company’s challenge to the larger Hudson’s Bay Company and American Fur Company, and did quite well for a time.

Constructing Fort Bridger

Sketch of Fort Bridger, 1852

Sketch of Fort Bridger, 1852 In 1843, together with Louis Vasquez, Bridger built a trading post on Black’s Fork, a tributary of the Green River. The fort, named Fort Bridger, became a mainstay for pioneers in need of goods while travelling overland on the Oregon Trail, as well as a way-station for the Pony Express.

By 1846 Brigham Young and his Mormons were travelling in the region looking for a permanent home, and Bridger informed them of the Great Salt Lake, telling them where it was and that it could in fact prove a hospitable area for them. The group moved into the region and made it their permanent home.

More and more travelers wanted to get to the Great Salt Lake, especially now that the Mormons were calling the area home. The South Pass of Wyoming had always been a difficult crossing, and in 1850 Bridger was searching around for an alternative. He found it while guiding the Stansbury Expedition back east from Utah in 1850, and the route ended up shortening the Oregon Trail by 61 miles. It was such a good path through the mountains that the Union Pacific Railroad would choose it as the place to lay track when they began building their lines through the region.

Problems with the Mormons

Ridgeline on Bridger Trail

Ridgeline on Bridger Trail The seizure of Fort Bridger probably had something to do with Bridger’s decision to lead federal troops into the region during the Mormon War of 1857-8. Brigham Young had been elected as the territorial governor of the region in 1849, but was not doing what Washington wanted, and so they appointed a new man, Alfred Cumming, in 1857. He was never allowed to take up his post, so President Buchanan ordered troops into the area.

General Albert Sydney Johnston led his 2nd US Cavalry force of 2,500 soldiers from Fort Leavenworth to the region during the winter, and the men suffered terribly for it, losing many mules and horses. They could have fared much worse if they hadn’t hired Bridger to guide them, a job which gave him the rank of major.

The Mormons vowed they would burn Salt Lake City to the ground before letting the federal troops in, but they never had to. Young had dispatched 75 men on a “Corps of Observation” to find out what the troops were doing. They burned both Fort Supply and Fort Bridger, although Johnston moved his troops into the remnants of the latter and used it as a base.

After being harried by Young’s men for several months, a compromise was reached and Cumming was allowed to take up his post. All of the Mormons involved were pardoned and the whole incident was forgotten as those in Washington probably thought it best to let them pass their time in their desert home.

Family and Frontiers

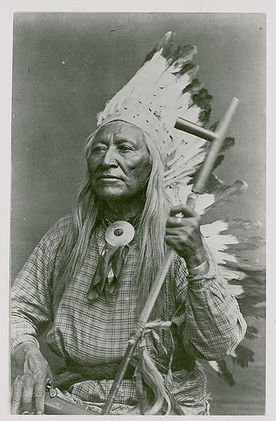

Chief Washakie

Chief Washakie Bridger then took either a Ute or Shoshone wife, but she died of complications from childbirth in 1849. The next year, in 1850, Chief Washakie of the Shoshone offered his own daughter to Bridger, and together they had two children. She would die in 1859.

Also in 1859 Bridger left St. Louis with Captain William F. Raynolds for Fort Pierre, in the Dakota Territory, with a large contingent from the Army Corps of Engineers heading toward the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers. They’re goal was to map the uncharted territory between Fort Pierre and the Yellowstone River, and it included seven scientists, seven congressional guests, and thirty military escorts. They had a hard winter, and returned to Omaha in the fall of 1860.

His work as a guide continued, and in 1861 he showed the way for the Edward L. Berthoud survey looking for a Denver to Salt Lake stage route. He also helped the U.S. Army find its way while attacking Sioux and Cheyenne along the Powder River in 1865-6.

The Bridger Trail

Map of Bozeman Trail

Map of Bozeman Trail The Bozeman Trail was becoming too dangerous, what with the Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Sioux Indians feeling threatened by the swelling tide of people coming into their territory, and they increased their attacks as a result. Bridger had travelled heavily in the area that would become the Bridger Trail during 1859 when he was doing reconnaissance.

Colonel William O. Collins of Fort Laramie knew of Bridger’s travels in the area, and being concerned about the situation, contacted Bridger to guide a group of settlers from Denver, Colorado, up through the Big horn Basin of Wyoming and along the Big horn Mountains into Montana. The trail was a success, and that spring and summer it saw 10 wagons ride through the mountains and into the state, two of them led by Bridger himself.

Bridger had to abandon the route the very next year, in 1865, when things began to heat up along the Bozeman Trail. The First Powder River Expedition was launched against the three tribes that had been hindering commerce and travel, and Bridger served as one of its guides. The soldiers destroyed an Arapaho village and established Fort Connor, but the Indians were neither defeated nor cowed, and they would continue their attacks into the future.

By that time Jim Bridger was suffering a rash of health problems, including arthritis, goiter, and rheumatism. He left Fort Laramie in 1865 and headed to Westport, Missouri, where his remaining days were spent as a gentleman farmer. He died on his Kansas City farm, peacefully in bed, on July 17, 1881. He was 77 years old.

Vestal, Stanley. Jim Bridger: Mountain Man. Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1946. p 1-56.

Palmer, Rosemary G. Bridger: Trapper, Trader, and Guide. Compass Point Books: Minneapolis, 2007. p 10-21.

Rodriquez, Junius P. The Louisiana Purchase: A Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, Inc.: Santa Barbara, 2002. p 51.

Janin, Hunt. Fort Bridger, Wyoming: Trading Post for Indians, Mountain Men and Westward Migrants. McFarland & Company, Inc.: Jefferson, 2001. p 78-82.

Ismert, Cornelius M. “James Bridger.” Hafen, LeRoy R. (ed.). Mountain Men and Fur Traders of the Far West: Eighteen Biographical Sketches. University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1965. p 252-65.