Gold Creek

James Stuart in 1868

James Stuart in 1868

Some stopped, and Gold Creek managed to build up a steady population and town called American Fork by the late 1850s. Granville Stuart, his brother James Stuart, and Reece Anderson all found gold there in 1858. Still, the area never really took off.

It wasn’t until the early 1860s that more prospectors put their pans to work. By that time the Mullan Road had opened allowing more of the miners from the overworked claims of California, Nevada, and Colorado to come into the territory easily.

Steamboats were also plying the waters up to Fort Benton, allowing more people to come from the east.

On July 28, 1862, one of those miners from moving up from Colorado, John White, found gold on a grasshopper-infested creek. The name stuck and Grasshopper Creek, originally called Willard’s Creek by Lewis and Clark, experienced a classic gold rush.

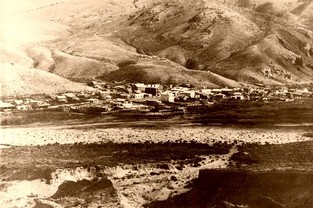

By that fall there were more than 300 people living twelve miles upstream in a settlement they named Bannack after the Bannack Indians of the area. Winter cut off the steady flow of prospectors but by the following summer Bannack had 1,000 people or more.

Alder Gulch

Bannack in 1881

Bannack in 1881

He’d have to defy government orders to prospect the area; it lay on Crow Indian lands which were forbidden to whites. Stuart didn’t care much about what the government said, but he did care about the Crows, or at least the risk they posed. A large group might be just the thing to dissuade attacks.

Stuart arrived in Bannack on April 7, 1863, and began moving his party out. He had fifteen men with him with the expectation that six more would join. Where they were, however, was a mystery to him and by April 12 the men weren’t to be found at the predetermined meeting point, the Stinking Water River, today’s Ruby River. He was forced to move on without them.

The six men, Thomas Cover, Henry Edgar, William Fairweather, Barney Hughes, Henry Rodgers, and Bill Sweeney, were on their way back from Deer Lodge with fresh horses for the trip.

They got held up and missed Stuart, but were determined to catch up with him. They nearly did just that until they ran into a group of Crows on May 1. The men were taken captive and led to the Indian village.

Escaping the Indians

Attack by Crow Indians, Arthur Jacob Miller, c 1858-60

Attack by Crow Indians, Arthur Jacob Miller, c 1858-60

While sitting in the Crow’s medicine lodge he picked up two rattlesnakes and put them down his shirt. The Indians became agitated and Simmons pulled them out. The stunt bought the men some time.

Later that night the men were taken to a pow-wow. The Indians would take turns giving short speeches haranguing the men and leading them around a bush.

After however many times of that Edgar got angry and told his companions he’d rip that bush right out of the ground the next time he was paraded around it.

He did just that when his turn came, and even hit it over the head of the Indian that was leading him. What would almost certainly have gotten a man killed didn’t this time; the Indians were more worried about releasing the evil spirit of the crazy man than any humiliation they might have felt.

The men took off at once and eventually continued after Stuart. They ran into some Indians in today’s Bozeman and had to fend them off, however. After that they decided it would be best to get off the main trails. They left the Gallatin valley and headed up the Madison River.

By May 26, 1863, they made camp on the East Slope of the Tobacco Root Mountains, choosing a spot for the night in a gulch near Wigwam Creek.

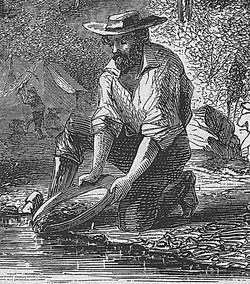

Panning for Gold

Panning the River

Panning the River

The men gathered their shovel and pick and headed on over. They dug a hole, filled up a pan with dirt, and Sweeney instructed the others to “wash that pan and see if you can get enough to buy some tobacco when we get to town.”

They found more than enough. Their first pan produced $2.40, the next $4.80, and the third $12.30. All told the men found $19.50 in gold that night, enough in fact that Sweeney thought they had ‘salted’ the pan, or put in their own gold to fool him.

The next day the men set to work with purpose. Cover and Hughes found $18 while Rogers and Sweeney found $4.50. It was Edgar and Fairweather who really lucked out though, finding $150 from the same place they’d panned the night before.

The men knew they had hit something big and by the morning of May 28 the ground was staked 100 feet along the creek. To make the claim permanent the secured water rights by digging a ditch and naming the site. Alder Gulch was chosen, since alder bushes dotted the area.

It was agreed by all that they’d keep the find a secret. The men knew full-well what news of gold could do, having seen first-hand how crowded Bannack had become. The men returned to Bannack to acquire more supplies, but somehow word of their find spread. As they were leaving town miners began following after them, sure that these men with gold-digging supplies had found something.

Seeing that they weren’t going to shake the miners, the six men stopped halfway between Bannack and Alder Gulch at the Point of Rocks. Terms were laid out and it was agreed that the six initial discoverers would be allowed two claims and the first choice of digging spots.

The Montana Gold Rush

Virginia City in 1866

Virginia City in 1866

By June 9 another meeting took place and rules for governing the new district were established, which was named Fairweather. Within three months the population of Alder Gulch soared to 10,000 along the gulch and what became known as the ‘Fourteen Mile City.’

The miners of the area needed to settle on a name for new city, and they settled on Varina, the name of Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ wife. A federal judge in Idaho Territory didn’t like that and refused their request by judicial fiat, naming the site Virginia City instead.

The towns of Adobe Town, Bear Town, Central City, Highland, Hungry Hollow, Junction City, Nevada City, Pine Grove French Town, Summit, and Virginia City all got pulled into one large mining camp area. And that mining area was anything but planned, laid out, or permanent.

The prospectors set up wikiups, a more primitive version of the teepee. Others created dugouts from overhanging rocks. There were no permanent structures at first, certainly not enough to house the men, so they did the best they could. As things continued to grow the first permanent building was constructed, the Mechanical Bakery.

Other structures soon followed, as did more prospectors. The gold placer deposits discovered by the six men that day in May, 1863, were just the tip of the iceberg. That first year saw $10 million worth of gold placer deposits taken from the gulch, and within just three years the total had reached $30 million.

Howard, Joseph Kinsey. Montana: High, Wide, and Handsome. Yale University Press: New Haven, 1943. p 38-9.

Pace, Dick. Golden Gulch: The Story of Montana’s Fabulous Alder Gulch. No Publisher: 1962. p 3-13.

Hamilton, James McClellan. History of Montana: From Wilderness to Statehood. Binford & Mort: Hillsboro, 1957. p 230-4.