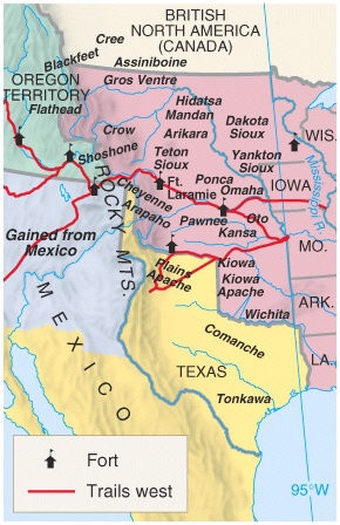

Indian reservations created by the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851

Indian reservations created by the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851

In 1851 government officials decided that it was time to negotiate treaties with the Indian tribes as the West opened up.

They called tribal representatives from all of the territories of the West to Fort Laramie in Wyoming.

What resulted was the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, and the beginning of the reservation system for Montana’s Indians.

Tribes ceded sections of their lands to the government for the building of both roads and forts. Each tribe was allotted a certain portion of land that was defined as its domain, and all tribes were expected to respect the land rights of their neighboring tribes. The Indians received assurances that they wouldn’t be bothered, and they also received many gifts of food and gifts, or what really amounted to trinkets.

Montana’s Indian Lands

Photo taken of Fort Laramie in 1858

Photo taken of Fort Laramie in 1858

Two tribes that called Montana home were left out of the proceedings entirely.

The Flathead, Kootenai, and Pend d’Oreille were given their own treaty four years later when Washington Territory’s Governor Isaac Stevens made a deal with the Indians that created the 1.2 million acre Jocko Indian Reservation just south of Flathead Lake.

The tribes agreed to their new home and the government also promised to pay for $120,000 in improvements to the reservation over the next twenty years.

Stevens further cemented ties with the Blackfeet, the tribe that had been left out of the Fort Laramie negotiations entirely. He went to them in October 1855, shortly after the Walla Walla Council in Washington, and convinced them to accept reservation lands from the Continental Divide east to the Milk River and from Canada to the Musselshell River.

In return the Indians agreed to keep southwestern Montana as a general hunting ground for all tribes and would even let whites use their lands to a limited extent. One of the most feared tribes in Montana’s history was suddenly made peaceful.

The Gold Rush and Montana Indians

Montana forts created after Montana gold rush

Montana forts created after Montana gold rush

So of course the Blackfeet began to retaliate, often stealing horses but occasionally killing as well.

This caused fears in the people coming into the area, and later territory. By the time the Civil War wrapped up in 1865 the federal government was free to focus its efforts more fully upon the West.

Forts began to be constructed with increasing regularity in the areas where settlers and Indians were coming into conflict the most.

Fort C.F. Smith was established in 1866 along the Big Horn River. Another fort, Camp Cook, was established the same year but didn’t last too long, and by 1869 the garrison relocated to Fort Benton.

The US army came true on its 1854 promise and established forts on the Blackfeet’s reservation lands. Fort Shaw came first in 1867 and was located along the Mullan Road at Sun River Crossing.

It primarily protected those journeying on the Mullan Road and the mining settlements from any Blackfeet threats. Fort Shaw was built later that year, following the death of John Bozeman and Indian scare that had developed around the growing city of Bozeman. The fort primarily protected against Sioux Indian threats coming from the Yellowstone valley to the east.

Montana Indian Reservations

The Death of John Bozeman, by Edgar Samuel Paxson, 1898

The Death of John Bozeman, by Edgar Samuel Paxson, 1898

The Department of the Interior recognized this in 1868 and began dividing the tribes up into various smaller entities. The Assiniboine, Blackfeet, and Gros Ventre tribes all received different subagencies, which were separate areas of land, a policy that would continue well into the next decades.

Each area of land would become smaller and smaller and those original treaties signed at Fort Laramie in 1851 and again with Governor Stevens in 1855 would prove meaningless.

In 1868 the government also signed new treaties with the Crow Indians. The crows had originally been granted lands by the Fort Laramie Treaty, but the mining stampede pretty much made those impossible to adhere to. The Bozeman Trail also wound its way through their lands, and clashes became frequent.

The government acted, and called forth the tribe to Fort Laramie again. A treaty was even drafted, but most of the Crow Indians refused to sign it. The government pushed it through anyway, and the Crows were given a reservation that took up a good portion of the southeastern part of the territory.

Unfortunately, new gold discoveries were made on these new Crow lands that same year, ensuring that the whole process would only have to repeat itself once again.

Brown, Dee. The Fetterman Massacre. University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1962. p.157-60.

Hebard, Grace Raymond and Brininstool, E.A. The Bozeman Trail: Historical Accounts of the Blazing of the Overland Routes into the Northwest, and the Fights with Red Cloud’s Warriors, Vol II. The Arthur H. Clark Company: Cleveland, 1922. p 103-11.

Malone, Michael Peter; Roeder, Richard B.; Lang, William L. Montana: A History of Two Centuries. The University of Washington Press, 1976. p 116-27.

McDermott, John D. A Guide to Indians Wars of the West. University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1998. p 156.

Olson, James C. Red Cloud and the Sioux Problem.University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1963. p 60-63.