James Beckwourth in 1860

James Beckwourth in 1860 A brother and sister travelled with him to St. Louis. The brother became a barber, while the sister became a prostitute. Jim spent four years in school in St. Louis before he became apprenticed for a time to a blacksmith when he was 19, and he even dabbled a bit in Andrew Henry’s passion, lead mining. But with Ashley’s help he became a mountain man.

Going Upriver

Beckwourth portrayed as Indian, 1856

Beckwourth portrayed as Indian, 1856 The men travelled as far as the North Platte before heavy snows overtook them as they were searching for the Green River. One story from the trip involved another black mountain man, Moses Harris, and Beckwourth loved to recount it years later.

The party’s provisions diminishing, Harris offered to walk to the Pawnee Indian village some 300 miles away. No one wanted to go with him, for the tales of Harris walking so fast that he left his companions behind were well known. Not even the bravest of men wanted to be left behind in Indian country, after all, so no one volunteered. Finally Ashley suggested that Beckwourth go. He reluctantly agreed, and the two set out the next morning, but instead of Beckwourth falling behind, it was Harris who couldn’t keep up, and in fact collapsed from exhaustion. They had travelled 30 miles with 25 pounds of food on their backs.

Beckwourth was lucky, and shot a few wild turkeys, which lasted them for a day. And it was a good thing, too, for when they reached the Pawnee village ten days later, they were out of food entirely, and there was no one about. The Pawnee had already left for their winter quarters, so Beckwourth and Harris had no choice but to continue on.

They lucked out two weeks later when they stumbled across a fresh trail left by Indians. By that time the two men had thrown away even their blankets, so weak were they. The only thing they had to sustain them for those two weeks in the wilderness was coffee and sugar, and perhaps the occasional root or berry, all the while walking in the dead of winter. It’s a wonder they survived at all.

It was evident to Beckwourth that only he could go, so weak was Harris. But when he told of his plans to leave him behind, Harris begged for his life. Beckwourth went anyway, and soon found two Osage Indians. Beckwourth retrieved Harris and they were brought to the Indian village and feasted like kings.

Second Thoughts

They headed back up to the men that Beckwourth and Harris had left the previous year, and didn’t find them in much better shape. They were nearly down to the last of their food supplies once again, and were soon on rations of just a single cup of flour a day, which was mixed with water into a kind of paste or gruel.

Beckwourth headed out with his rifle and shot a duck, considered sharing it, but devoured it instead. He wanted strength for what he intended to do next, which was find larger game. And he did, downing four deer and wolf. His companions cheered his return, but his guilt over the unshared duck weighed heavily on his mind, even when the others told him it was the right thing to do.

By April 19th, 1825, the men finally found the Green River. The area was rich in trapping opportunities, and within just a few short days they had over 100 furs, worth $1,600 downriver in St. Louis. Still, that didn’t leave much for each individual man, and Beckwourth received most of his pay in trade goods that he’d need to find more furs. He was consoled by the sight of Jedediah Smith and J.H. Weber, however. Both men had been out in the wilderness for two years, and they made quite haul at that first rendezvous.

A Native at Heart

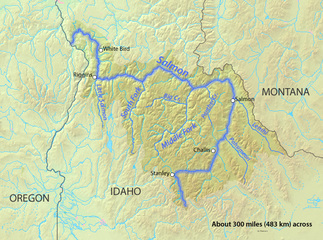

Salmon River

Salmon River Robert Campbell’s trapping party was in the area, and Beckwourth and a friend named Calhoun rode out to meet them while heading to Bear Creek for a new rendezvous. The whole party was set upon by Blackfeet, and pinned down for five hours. They were about out of ammunition when Beckwourth suggested they make a break for it. He and Calhoun did just that on the party’s fastest horses, and somehow managed to ride through a hail of Blackfeet gunfire without getting hit. By the time they returned to the party with help, the Indians were long gone.

While that story was true, Beckwourth was known to tell tall tales around the nightly campfire, and he soon became known for his exaggerated wit and interesting lore. Many stories told by others claimed that Beckwourth was a Crow Indian, the son of a chief in fact, who had only been brought to the wider world when a band of Cheyenne Indians stole him as a baby and sold him to whites. Beckwourth so acted like an Indian for many years that many believed the story.

One story that has a bit more weight to it involves Beckwourth living with the Crow. Beckwourth claimed that he was captured by the Indians, but accounts from the Rocky Mountain Fur Company paint a different picture. Beckwourth went willingly to the Crow to open up trade relations with the Indians at the company’s behest. And it was with the Crow that Beckwourth may have married the first of his many native wives.

It was common for mountain men to marry the natives, for not only did it give them valuable friends in the wilderness, but it also opened up new avenues for trade with their respective fur companies. And Beckwourth was a fan of marriage. By all accounts, he had four different wives, two of them Indian, one Hispanic, and the other African American. And he had numerous children by them, probably more than he even knew, for he was always going from one place to the next, exploring and trapping.

Moving On

Map of Salmon River

Map of Salmon River When not out raiding, Beckwourth was out trapping, and he had a few good years with the American Fur Company. By 1837 the fur trade was changing, however, and the American Fur Company chose not to renew his contract. He headed first to St. Louis, and then to Florida, where the Second Seminole War was being waged, already in its second year.

By 1838 he was back in his old stomping grounds in the west, working on the Arkansas River and trading with the Cheyenne, as well as around Fort Vasquez in Colorado. He worked for the Bent & St. Vrain Company for a bit in 1840, and then teamed up with some partners to build a trading post in Pueblo, Colorado.

By 1844 Beckwourth was trading on the Old Spanish Trail that led from the Arkansas River to California. The Mexican-American War broke out in 1846, and Beckwourth did quite well serving as a courier for the US Army. During one daring raid into Mexico, he managed to abscond with 1,800 horses.

Going to California

Pyramid Lake, Nevada

Pyramid Lake, Nevada The pass became known as Beckwourth Pass, and he continued to improve another trail that would become the Beckwourth Trail, an old Indian path from Pyramid Lake, through Beckwourth Pass, and into the gold fields at the northern California town of Marysville. It was quite a trail, and saved people 150 miles of steep and treacherous mountain passes, like those found on the Donner Pass 70 miles to the south.

It was while living and ranching in the Sierra Nevada that he made his largest footprint on history. He had opened a hotel in what would become Beckwourth, California, and over the winter of 1854-5 a man named Thomas D. Bonner checked in. Beckwourth indulged the man in his whole life story, and Bonner wrote it up, and the following year sold the book to Harper & Brothers in New York.

The Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth hit the market in 1856, and although Beckwourth was to receive half of the profits, he never received a cent from Bonner or Harper & Brothers. While the book may not have been a runaway success, or made Beckwourth a nickel, it did tell later historians how the US government often used alcohol to subdue and negotiate with Indians, as well as the impacts of massacres and war on them.

Back to Montana

Beckwourth Pass

Beckwourth Pass Colonel John M. Chivington’s campaign against the Cheyenne and Arapaho led to the Sand Creek Massacre, an action that resulted in the deaths of between 70 and 163 innocent Cheyenne men, women, and children. The Indians had been staying in an area approved by the former commander of the nearby Fort Lyon, and had even flown an American flag to show where their loyalty lay.

Beckwourth had traded with the Cheyenne more than 20 years earlier, and his heart surely sunk at the atrocity. He was banned by the tribe from trading with them again. He decided to try his hand at fur trapping once again, even though he was well into his 60s and the fur trade was almost non-existent by that point.

His final job was as a scout for the US Army around Fort Laramie and Fort Phil Kearny in 1866. He was guiding some soldiers to a band of Crow Indians in Montana when he came down with uncontrollable nose bleeds and severe headaches, most likely brought on by hypertension. He died in the Crow Village on October 29, 1866. He was 68 years old.

Haggard, Dixie Ray (ed.) African Americans in the Nineteenth Century: People and Perspectives. ABC-CLIO: Santa Barbara, 2010. p 152.

Manheimer, Ann S. James Beckwourth: Legendary Mountain Man. Twenty-First Century Books: Minneapolis, 2006. p 16-26.

Oswald, Delmont R. “James P. Beckwourth.” Mountain Men and Fur Traders of the Far West: Eighteen Biographical Sketches. Hafen, LeRoy R. (ed.) University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1965. p 162-85.

Rodriquez, Junius P. The Louisiana Purchase: A Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, Inc.: Santa Barbara, 2002. p. 28-9.

Van Ravenswaay, Charles. Saint Louis: An Informal History of the City and its People, 1764-1865. Missouri Historical Society Press: Columbia, 1991. p 215.

Wilson, Elinor. Jim Beckwourth: Black Mountain Man and War Chief of the Crows. The University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 1972. p 31-40.