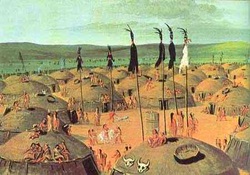

"Mandan Villages" by George Catlin, 1833

"Mandan Villages" by George Catlin, 1833 Drouillard joined on with Lewis and Clark and voyaged with them all the way to the Pacific and back to St. Louis before taking his leave of them in 1806. Clark praised him highly, and considered him indispensible to their exhibition. He was often given the most difficult jobs to perform, not because no one else wanted to do them, but because no one else could.

Solo Journeys

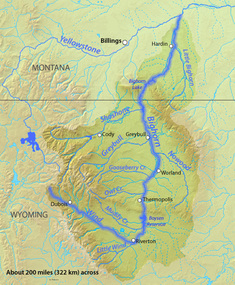

Map of Bighorn River

Map of Bighorn River George Drouillard made two journeys into the wild on his own, one in the spring of 1808, and one in the winter. He roamed about Montana, visiting the Bighorn Basin and “Colter’s Hell,” as Yellowstone came to be called, as well as the Bighorn and Little Bighorn Rivers. Drouillard made a detailed map of the rivers, and it was used by William Clark to augment his own maps.

Working for the Missouri River Fur Company

Site of the 1810 attack

Site of the 1810 attack They set out from St. Louis in early spring, but ran into problems by April. Stopping to trap for awhile, a small party out in the wilderness was set upon by a group of Blackfeet, and eighteen men were killed. The men were on the Missouri and nearly up to the Jefferson River, but this latest attack was just too much. Several men quit the party and headed back down river, including Colter.

The Blackfeet were angry at Lisa’s men, for several reasons. First, they didn’t like the fact that Fort Henry, the groups winter camp on the Snake River, had been built without their permission. Also, the Blackfeet frowned upon trapping on lands they considered theirs, even though they had stolen those lands from the Indian tribes that had lived in the area before the Blackfeet pushed them out. And finally, Lisa and the Crow Indians had traded before, the Blackfeet knew this, and took offense. They were, after all bitter enemies, and they expected the whites to know this.

A Savage Death

The Jefferson River

The Jefferson River George Drouillard didn’t like the arrangement for some reason, and headed out alone. The others chided him for this, but he simply answered that he would never be killed by Indians because he was just too much like one himself. His strategy worked, and he brought quite a haul of furs back to camp.

But on the third day his luck ran out. He and two other men set out from the main party early. When the rest of the men got packed up and headed after them, they found the two men dead, obviously killed by the Blackfeet. 150 yards on lay Drouillard’s decapitated body chopped into pieces, the entrails all about.

It was obvious from the scene that he had put up quite a fight, circling his horse to use as a shield, and he may have even taken several Blackfeet with him. This could explain why they mutilated his body, so angered were they at what one man could do when outnumbered.

Still, the death of George Drouillard, as well as the other men of the 1810 expedition, spelled the end of the Missouri Fur Company’s attempts to set up shop around the Three Forks area. It also showed how dangerous life as a fur trapper and mountain man could be. Montana in the early 19th century was still an untamed wilderness, and opening it up to trade and settlement wouldn’t be fast or easy. George Drouillard’s death proved that even the most well-known and experienced of mountain men could die if they became careless.

Malone, Michael Peter; Roeder, Richard B.; Lang, William L. Montana: A History of Two Centuries. The University of Washington Press, 1976. p 47-48.

Utley, Robert M. After Lewis and Clark: Mountain Men and the Paths to the Pacific. University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1997. p 11-22.