Mountain Man Seth Kinman, 1864

Mountain Man Seth Kinman, 1864 Mountain men were solitary individuals, often going out alone or in small groups to hunt and trap. They would spend months out away from civilization, but this didn’t mean that they didn’t like to get together once in a while. These get-together’s were called rendezvous, and the fur trading companies that employed these rugged individuals not only encouraged these sporadic encounters, but often relied upon them for their profits, and even survival.

The mountain men set out for the Rocky Mountains for a variety of reasons, including the urge to explore and open up trails to the west. And all were driven by profits from the growing fur trade. While independence is one of the traits most often associated with the mountain men, the truth was that many were financially dependent upon the fur companies that employed them.

A Life of Independence

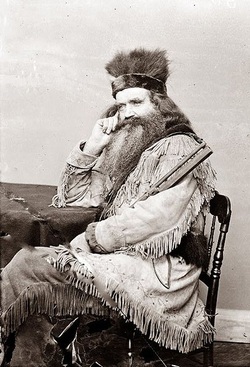

Hawken rifle

Hawken rifle The company man worked for one of the fur companies, and he had to accept whatever price they would give him for his furs. The company man also often found himself taking orders from company representatives and agents, either by telling him where to go or which specific furs to focus upon. The free agent was beholden to none but the market, and could seek out the best price he could find.

The price of the furs was often set by the company, and at lower-than-market rates. At the first rendezvous held in 1825, William H. Ashley of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company paid $3.00 for a pound of beaver furs to men that had been working for him for some time, and $2.00 per pound to those who joined him around 1822-1823, most likely because or a prearranged agreement.

Those mountain men that were able to operate as free agents, however, received $5.00 per pound. Based on the amount of furs that came out of the first rendezvous, we can determine that one fur weighed about 1.64 pounds, and was worth $4.92 if sold at $3.00 per pound. Free agents were therefore getting $8.20 for the same work that company men were doing.

Mountain Life

Pemmican cooking

Pemmican cooking Many of the most notable mountain men used the Hawken rifle, the first of which was made for William H. Ashley in 1823. Each rifle was made by hand individually, and ranged between .50 and .68 caliber. They weighed about 10 pounds and were quite accurate, even at long range.

Horses were another necessity of the mountain men, or if unobtainable, mules. The weight of a fur by itself was nothing, about 1.64 pounds or less, but when you factored in all the furs taken over a winter season or longer, it quickly added up, and such weight was unmanageable without an animal to carry the load.

The mountain men’s diets consisted of about the same types of foods that were eaten by the Indians. They subsisted on the game they found and the fish they caught. Roots and berries also supplemented their fare.

Most also carried pemmican, which was the lean meat from animals like bison or deer. It was dried over a fire or left out in the sun until it became hard, at which point it was pounded nearly into dust before being mixed with an equal amount of fat. Berries were sometimes beaten into powder and added, and the resulting mixture was stored in the men’s pouches for later consumption. It might not sound like the most appetizing dish, but when game was scarce and the rivers and steams were all frozen, it came in quite handy.

Baird, John D. (1968). Hawken Rifles: The Mountain Man's Choice. The Buckskin Press: Tryon, 1968. p. 1-5, 44-5.

Gowan, Fred R. Rocky Mountain Rendezvous: A History of The Fur Trade Rendezvous 1825-1840. Gibbs Smith: Layton, 2005. p 12-20.

Hafen, LeRoy R. (ed.). Mountain Men and Fur Traders of the Far West: Eighteen Biographical Sketches. University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1965. p xiii-xvi.

“Pemmican.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 23 March 2013. Web. 24 March 2013. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pemmican>