Lead Mining on Upper Missouri, 1865

Lead Mining on Upper Missouri, 1865 But trapping and exploring were never Henry’s true passions, and he left the fur trade on several occasions to try his hand at soldiering and mining. However, the men he led on his expeditions up the Missouri would form the backbone of the Rocky Mountain fur trade, and without his leadership, many of them may have never done for which their names are remembered today.

A Miner at Heart

Current River, where Henry mined

Current River, where Henry mined It was while working and living in Potosi that Henry came to the attention of William H. Ashley. Ashley had tried his hand at being a merchant, but it just didn’t pan out. Most likely through late-night talks stewing over his frustrations, Ashley was convinced of the promise of the mines by Henry, and he soon was involved in the operations of several.

But mining wasn’t as interesting as making money, and Ashley turned his attention to the growing fur trade, and began devising options. He knew he needed backing for his plans, so in 1808 he gathered together all of the richest merchants of St. Louis, as well as some of the city’s most powerful families. They formed the “St. Louis Missouri Fur Company,” and gave it $40,000 to get underway. The first expedition of 150 men was led by Manuel Lisa in 1809, and the second by Henry in 1810, which numbered thirty-two.

The 1810 Henry Expedition

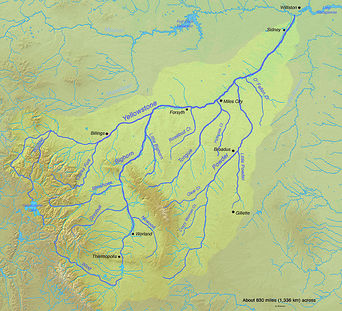

Map of Missouri River

Map of Missouri River And perhaps most importantly, Henry had a reputation for honesty. A shrewd businessman, Ashley had undoubtedly heard many tall tales and excuses in his time, and someone who could tell it straight without embellishments surely appealed to him. Still, Henry was only a joint-commander, and Pierre Menard also had a leadership role on the expedition.

The expedition was not a success. While it’s true that the trading post of Fort Henry was built at Three Forks, and the men found some excellent trapping opportunities in the area, the loss of life and anger incurred from the Blackfeet was considered too high a price. The Blackfeet, instead of happily accepting the offer of trade that Henry and his men hoped to make, attacked the expedition, killing eight men including George Drouillard. The attack occurred just 2 miles from the Fort Henry, and showed that the area was still anything but untamed by their presence.

A Break and a Return

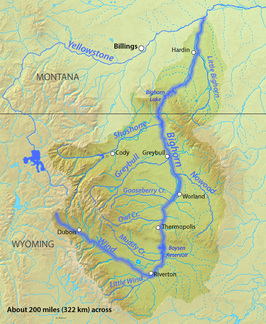

Map of Yellowstone River

Map of Yellowstone River When war broke out with the British in 1812, he joined the army and rose to the rank of major. When the war concluded he again returned to lead mining, and even married the French daughter of one of the mine’s owners.

Ten yeas of mining is often more than enough for anyone, and by 1822 Henry was once again pulled into the fur trade. By that time Ashley had been elected as Missouri’s first Lieutenant Governor, a post he held from 1820 to 1824, and his interest in the fur trade had only risen over time. Henry partnered with Ashley to form the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, and they quickly organized three expeditions. One was to be led by Henry, another by Daniel Moore, and the third by Ashley himself.

Map of Bighorn River

Map of Bighorn River Henry learned that Ashley’s expedition had suffered similar losses against the Arikara Indians. The two men decided to continue on as best they could, and Henry travelled to the Big Horn River where he set up a trading post with the Crow Indians. They also resolved to trap and trade in less hostile areas, and Henry’s time in Montana was effectively at an end.

By 1824 Henry decided he’d had enough of the fur trade. He’d made quite a bit during the previous season, especially with the new rendezvous system that Ashley was beginning to pioneer. He was also nearing 50 years of age, and the rigors of river travel and the constant threat of Indian attacks probably didn’t appeal to him anymore. Fur trapping was a young man’s game, after all, and Henry’s moment had come and gone. He returned to the mining industry, either mining lead or fashioning the bullets, and died in Missouri on January 10, 1832.

Carter, Harvey L. “William H. Ashley.” Mountain Men and Fur Traders of the Far West: Eighteen Biographical Sketches. Hafen, LeRoy R. (ed.) University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1965. p 81-3.

Chittenden, Hiram Martin. The American Fur Trade of the Far West [Vol 1]. University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1986. p 249-50.

Malone, Michael Peter; Roeder, Richard B.; Lang, William L. Montana: A History of Two Centuries. The University of Washington Press, 1976. p 48-50.

Neihardt, John G. The Splendid Wayfaring: Jedediah Smith and the Ashley-Henry Men, 1822-1831. State University of New York Press: Albany, 1948. p. 31-34.

Rodriquez, Junius P. The Louisiana Purchase: A Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, Inc.: Santa Barbara, 2002. p. 17.