It’s a question many in Montana ask themselves each year, especially here in Missoula when HSTA 255 – Montana History starts up each fall.

While Montana history at the University of Montana is no longer taught by a native Montanan – perhaps the first time since the early 1900s – it is being taught. And that means students are hearing the thoughts and ideas of K. Ross Toole.

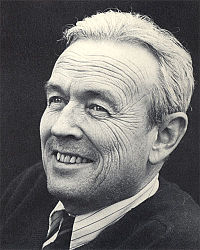

So…who was K. Ross Toole? Wallace Stegner wrote the Foreword to Montana and the West: Essays in Honor of K. Ross Toole, a book that was edited by Rex C. Myers and Harry W. Fritz and came out in 1984. It’s a short volume – just 186 pages, not counting notes – but has eleven essays that explored the themes Toole himself explored.

Toole’s main course at the University of Montana was History 367, “Montana and the West.” He taught it for sixteen years, from 1966 until his death from lung cancer in 1981. During the last year it had 1,700 students. “He did not lecture with professional caution, and he abandoned scholarly detachment,” long-time University of Montana history professor Harry W. Fritz writes. “Students loved it.”

“Ross Toole’s Montana contained the color and exuberance of the early frontier – Custer, Vigilantes, and the flamboyant entrepreneurs,” historian Rex C. Myers tells us. “Yet Toole did not permit his students – graduate or undergraduate – to linger in the past at the expense of the present.”

Toole was a product of Montana’s past, its earliest beginnings in fact.

K. Ross Toole was born in Missoula on August 8, 1920. He was a fourth-generation Montana, and on both sides of the family. His great-grandfather, Cornelius C. O’Keefe, “had settled in the Missoula valley in 1859,” Fritz tells us, while another, Alan “Doc” Hardenbrook, made it here in 1864. Ironically, two of his grandfathers worked for the very company that their grandson would come to revile – Anaconda. While it’s true that it was just the Anaconda Lumber Company in Bonner, both were in high positions – “John R. Toole was president and Kenneth Ross was general manager.”

K. Ross Toole graduated high school in Missoula in 1939 and immediately enrolled in the University of Montana, beginning “an educational odyssey that lasted twelve years.” His record was far from noteworthy, as Fritz points out. “In eight undergraduate years at four institutions he compiled a gentleman’s C average.” Perhaps it was the skipping from UM to Georgetown and then back to UM’s School of Law, something that lasted two weeks. “He stunned his family by quitting abruptly and heading for Alaska,” Fritz writes, “where he worked for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.”

World War II got in the way of his schooling at that point. Toole did another five quarters at UM – roughly a year and part of a semester – before he joined up with the Navy. Instead of shipping him out, the Navy sent him to Carroll College in Helena and then to Columbia University for a time. Finally he was sent overseas to the Mediterranean for a span and then to Hawaii, though he only managed to man a desk. War over, Toole headed back to UM, finishing his BA in 1948 with the thesis “Marcus Daly: A Study of Business in Politics.” Paul Chrisler Phillips was the professor that guided him, as he’d been doing for Montana students since 1911.

By 1951 Toole was back in Montana, serving as director of the Montana Historical Society. He didn’t have a Ph.D. but he was chosen for the job and would hold it for seven years. As Fritz writes,

It would be at once the most frenetic and the most productive of his life. During this period he brought the quiescent historical society to life. He installed the latest in museum displays, ceaselessly promoted and advertised his operation, and earned a national reputation for the society’s historical quarterly. For a year Toole edited and published a liberal journal of opinion. He finished his doctoral dissertation on June 6, 1955. With Merrill Burlingame, he coauthored the last (and best) of Montana’s subscription histories, and with John W. Smurr he issued Historical Essays on Montana and the Northwest. And he wrote Montana: An Uncommon Land. (p 6)

When Toole came in that agenda went right out the window and instead the society began training people how to use its materials, a great way for residents of Montana to discover history for themselves. Grants were given to researchers and materials were updated. The archives and attics were also explored. “They had three skulls of Henry Plummer,” Toole remembered of his early organization efforts.

Toole was always busy with other tings during that time, and Fritz notes that he “worked actively on five major projects, which together would establish his reputation as historian and gadfly.” One of his efforts was Montana Opinion, “a short-lived journal” (four issues) that “subjected Anaconda and state institutions to muckraking attacks.” The media wasn’t spared, for Toole decried its poor state and how residents were “sick and tired of living without a candid and intelligent press.”

The defining work of this time, however, was Montana: An Uncommon Land. It was slated to be put out by the University of Nebraska Press, but they ran into money problems. Toole brought it to the University of Oklahoma Press, and they happily took it. Interestingly, the name “An Uncommon Land” was actually chosen by Toole’s secretary, and kept over the University of Nebraska’s suggestion of “The Forty-first Star.”

The book “stamped Toole as the premier historian of the state,” Fritz writes. Still, it wasn’t enough for him to want to keep on at the Montana Historical Society, and he quit in 1958. The reason? Primarily the fact that he was tired of fighting the Montana Legislature for funding. What’s more, raising funds had become increasingly difficult. “His espousal of liberal causes in Montana Opinion had earned him the enmity of a cadre of legislators, trustees, and the public.

“After seven strenuous years as director of the Montana Historical Society he resigned in a rage,” Wallace Stegner writes, “and spent the next seven years wandering in the wilderness: first New York, then Santa Fe.” Still, Stegner makes it clear that Toole may have been the most to blame:

But what drove Ross out of Helena and the Montana Historical Society was not a weakening of his interest in history. It was outrage that in site of heroic efforts he had been unable to teach respect for it to Montana politicians and educators…like the pronouncements of the Delphic Oracle, what Ross said affected men’s actions, and he was passionately respected and thoroughly loathed in consequence. It is hard to bloody noses without making enemies.” (p ix)

“He was capable of the most disparaging remarks about university faculties, historians in particular,” Fritz writes. “They constituted a ‘priesthood, protected, profoundly ignorant…isolated, insulated, shortsighted.” To Toole it just seemed “pretty silly to proceed into the future if you don’t know where the hell you came from.”

Toole used his polemical abilities well, and hit the pulse of the dying counterculture and student rebel days on campus with his diatribe called “The Tyranny of Spoiled Brats.” Going after the burgeoning Baby Boomer generation, Toole excoriated them in such a way that

five hundred newspapers and magazines reprinted the piece; twenty thousand letters poured into Missoula; talk-show invitations arrived from coast to coast. Toole capitalized on the publicity and the obvious market. The resulting book, The Time Has Come, was a Book-of-the-Month Club alternate selection and paid ‘hefty royalties.’ (p 12-13)

No, instead Toole was the kind of historian that

became an attentive student of the corporate (and often criminal) records of the great piratical corporations, eastern-financed but often western-generated, whose power in Montana’s development was irresistible and ruthless. (p viii).

His version of Montana history was theirs; it made sense in their time. The past was not dead; the cycle had not run its course; history was alive, it taught real lessons, and students learned them in class and out. To Ross Toole, the university was no ivory tower, but a platform from which to fire up the armies of the future.

“In the last months of his life, during a remission of the cancer that killed him in 1981,” Stegner writes,

he devoted his final energy to lobbying the legislature in Helena in support of the bills, mainly environmental, that he felt to be crucial…this is the consequence of developing a historian who is also patriot and a champion: others find in him the cues to further words and further action.”

“Once I called him the best talker in Montana,” Stegner writes, “but I could just as well have said the best talker about Montana.” But as we saw, he didn’t just talk about the past. “Not content with excoriating past evils,” Fritz writes, “he strove to prevent new ones.” He was amazingly successful at it, so much so that we may not even know it yet. “His influence is pervasive and statewide,” Stegner writes, “and has not even yet been felt in its full force.”

By the time he died on August 13, 1981, Fritz writes, “Toole was one of Montana’s most outspoken public personalities, mourned statewide as the historian who told us who we were.”