Yellowstone Falls by Thomas Moran, 1872

Yellowstone Falls by Thomas Moran, 1872

The geologic history of the park goes back eons, although white men didn’t come to learn of it until the late 18th century and early 19th century.

Nothing much happened after that. Montana was a sleepy backwater until the 1860s when gold was discovered, and while more travelers may have stumbled upon the park both purposefully and otherwise during that time, it largely remained untouched by man.

That’s how most conservationists wanted it, and they lobbied hard for Congress to protect the park, something that was done in 1872. Much of that lobbying, however, didn’t come from Montanans but from people that often weren’t even in the state.

Yellowstone Falls

Yellowstone Falls

Even when the park was protected, poaching and other illegal activities remained endemic, and seriously threatened both the park’s existence and reason for being. After all, the creators had envisioned a place where all could come and enjoy wildlife, not hunt it.

Perhaps most interesting of all, however, is how the short-term gain of those living around the park can in no way be measured against the long-term economic and cultural benefit that Yellowstone Park has brought to Montana and its people, as well as citizens from around the world.

Yellowstone National Park and its creation is just another of many examples where Montana’s own citizens have been short-sighted about what’s best for the state long-term.

The Early History of Yellowstone

Map of Yellowstone River

Map of Yellowstone River

The first white man to lay claim to discovering the park, or at least getting the word out to the rest of the world, was John Colter. During the winter of 1807-8 Colter wandered into the area that would become the park and the place was known as “Colter’s Hell” for some time to come.

Many other travelers saw it the in the years that followed, especially as more people began coming into the area as the fur trade took hold and declined. One, Jim Bridger, entered the park in 1856 and told about it, but most never listened to what the known-teller of tall tales had to say.

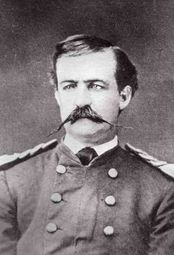

The Raynolds Expedition

William F. Raynolds

William F. Raynolds

Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden, 1860

Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden, 1860

While many may have dismissed Bridger’s tall tales, Raynolds did not, and he hired the mountain man to guide the party. He had the money, the federal government had authorized $60,000 for the expedition, and he also had protection in the form of a small detachment of infantry.

The group made it as far as Wyoming before winter set in, and then in May of 1860 they made to cross the Continental Divide at Two Ocean Pass, where the unusual “Parting of the Waters” is located.

Here the North Two Ocean Creek splits into two different creeks: Pacific Creek which flows west and Atlantic Creek which flows east. Both eventually join other rivers and empty into their respective oceans.

Unfortunately no waters were flowing to either ocean at that time of year as the pass was still snowed-in. The group turned back, upset, but determined to make another go of it in the near future.

Wind River Range, Wyoming

Wind River Range, Wyoming

The group did manage to explore the Wind River Range extensively, as well as other areas of the Rocky Mountains and what would become Wyoming.

One tall peak was named by Raynolds – Union Peak – and they also came down into Jackson Hole. All of this only emboldened other explorers to visit the area.

The Cook-Folsom-Peterson Expedition

All three men were from a cold camp called Diamond City off Confederate Gulch near Helena. Cook and Folsom in particular were good at keeping diary records of what they saw and did, and it was those accounts which interested the men setting out the following year.

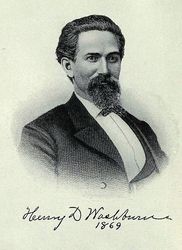

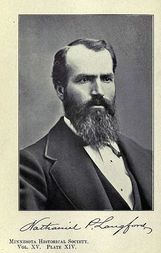

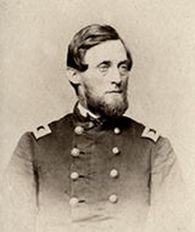

Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition

This group included Henry Washburn, Nathaniel P. Langford, and Lieutenant Gustavus C. Doane. Langford had become famous as a vigilante while Doane had taken part in the Marias Massacre earlier that year. The men stayed around the area for a month collecting samples and making recordings in their notebooks and diaries.

Those records would come in quite handy, and go a long way in ensuring Yellowstone would enter the public consciousness. Lieutenant Doane filed his official report with the Department of War in Washington while Langford hit the lecture circuit in the East over the winter and spring, finally writing up his account in an article for Scribners called Wonders of the Yellowstone which appeared in May of 1871.

One person with them, Cornelius Hedges, advocated that the area should become a national park. This was really nothing new, as Thomas Francis Meagher had suggested the same thing back when he was serving as Acting Governor in 1865.

What was different this time is that Hedges wrote a series of newspaper articles in the Helena Herald from 1870-1 that really got public opinion behind the idea locally. Together with Langford’s push back East the issue was gaining steam.

Hayden Geological Survey of 1871

Hayden Geological Survey of 1871

Hayden Geological Survey of 1871

The Hayden Geological Survey of 1871 was organized, and it was Hayden’s reports and also the photographs and paintings made by others, particularly Thomas Moran, that convinced Congress to not offer the land up for public auction as they had been planning to do, and instead they recalled it.

On March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant put his signature to The Acts of Declaration, the law that created Yellowstone National Park.

Montanans Were Not Happy About Yellowstone

To them it seemed like federal meddling in their affairs, and on their land. There was widespread speculation that the area would lose its economic value, that it couldn’t be used for its resources. Thankfully such short-term thinking didn’t take hold.

The Helena Gazette declared in 1872 that the creation of Yellowstone was “a great blow to the prosperity of the towns of Bozeman and Virginia City.”

These were legitimate observations as many in the area were worried for their livelihoods. Locals wanted mining, hunting, and logging to take place within the parks boundaries, and they urged their representatives to Washington to introduce legislation to do so, which they did.

For every session of Congress from 1872 until the 1890s there were bills introduced seeking to strip the land of its park designation. Fortunately there were wiser heads in the capitol and these efforts all failed.

The Lacey Act in 1900

Finally in 1900 the Lacey Act was passed by Congress which finally gave the poaching laws the teeth they needed in the form of adequate funding and legal support for prosecutions. By the time the National Park Service was created in 1916 Yellowstone was a model for the nation. On October 31, 1918, the U.S Army formally turned over governing duties of the park to the NPS, which as had them ever since.

Any resource exploitation engaged in by the locals would have been short-lived, helping only a generation at most, perhaps some of the children that came after. Yellowstone National Park has created countless jobs and billions of dollars in revenue for the State of Montana.

It goes to show that many times those in Montana don’t always know their own best interests. If short-sighted opinions of a few locals around Yellowstone had been acted upon, opinions put forth only to ensure their own economic gain, countless generations would have lost out.

Notes

Bartlett, Richard. Yellowstone: A Wilderness Besieged. University of Arizona Press: Tucson, 1985. p. 12-73.

Grusin, Richard. Culture, Technology, and the Creation of America’s National Parks. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2004. p 54-69.

Haines, Aubrey L. Yellowstone Place Names-Mirrors of History. University of Colorado Press: Niwot, 1996. p. 45-55.

Langford, Nathaniel P. The Discovery of Yellowstone Park: Diary of the Washburn Expedition to the Yellowstone and Firehole Rivers in the Year 1870. The Haynes Foundation: 1905.

Schullery, Paul and Whittlesey, Lee H. Myth and History in the Creation of Yellowstone National Park. The Yellowstone Association: Gardiner, 2003. p 2-4.

Wilkins, Thurman. Thomas Moran: Artist of the Mountains. The McCasland Foundation: Duncan, 1996. p 5-23.

You Might Also Like

Useful National Park Service Yellowstone Pages

5 Great Montana History Books

Henry Plummer and the Montana Vigilantes