The book follows mountain man John Colter as he goes back up the Missouri River in the summer of 1807 and then out into the rough winter of 1807-8.

The latter he did alone, with just himself and a 35-pound pack. He had a gun too, and I’ve given him a Northwest Trade Gun, or a Barnett Trade Gun as they were often called.

Manuel Lisa, another main character, has a Brown Bess, which is what the British muzzle-loading smoothbore muskets were called.

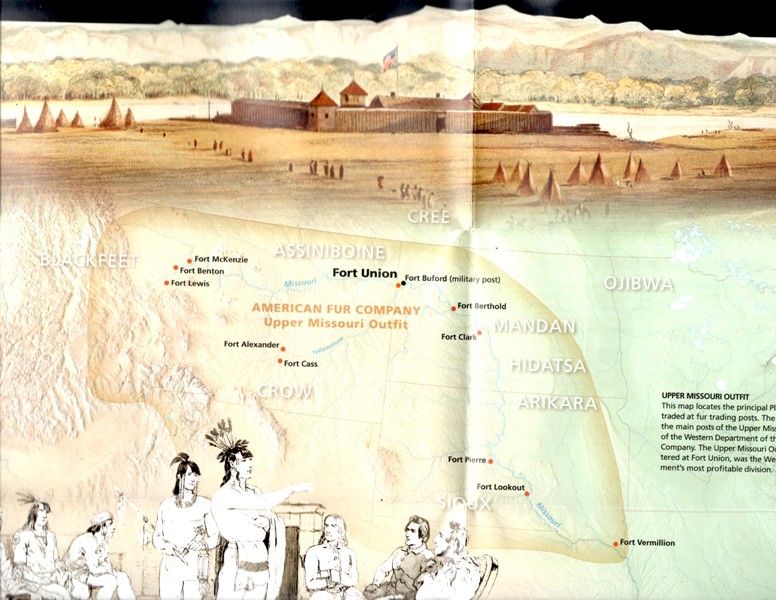

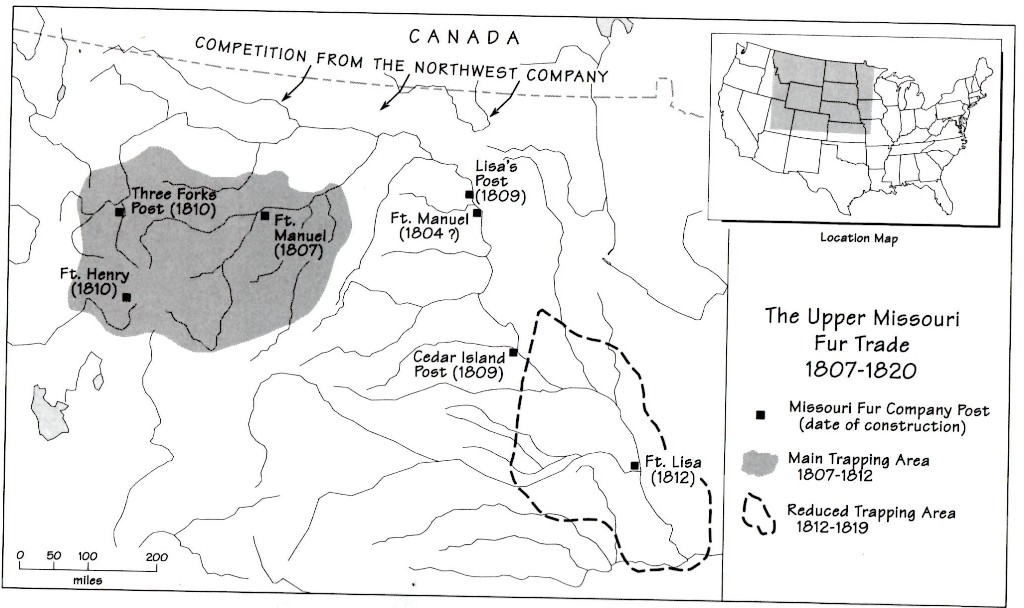

They’re the men that headed up the Missouri with Manuel Lisa to build Fort Raymond, and they reached its spot on November 21. I have no idea when the fort was finally finished, but put it at early-January in my novel.

It is a novel, though one with lots of history that I’ve thoroughly researched. I did that research online, at the Montana Historical Society in Helena and at the Missoula Public Library’s Montana Room. So this book is accurate…though not factual.

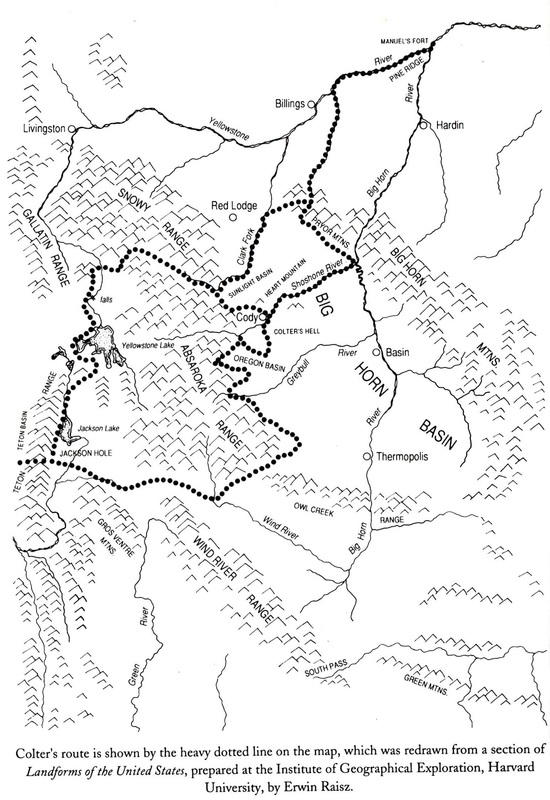

What does that mean? Well, if I wanted to stick to the facts, we’d have a pretty boring story on our hands. The facts are that Colter went out that winter and walked around in a big circle before coming back, that’s the gist of it (the complete route is listed below, with images).

Pretty boring, huh? I suppose I could have thrown in some grizzly bear attacks or maybe some run-ins with an angry moose, but instead I chose Indians.

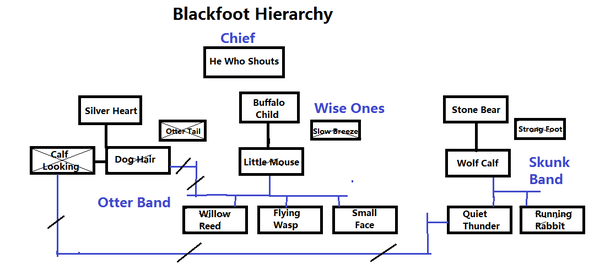

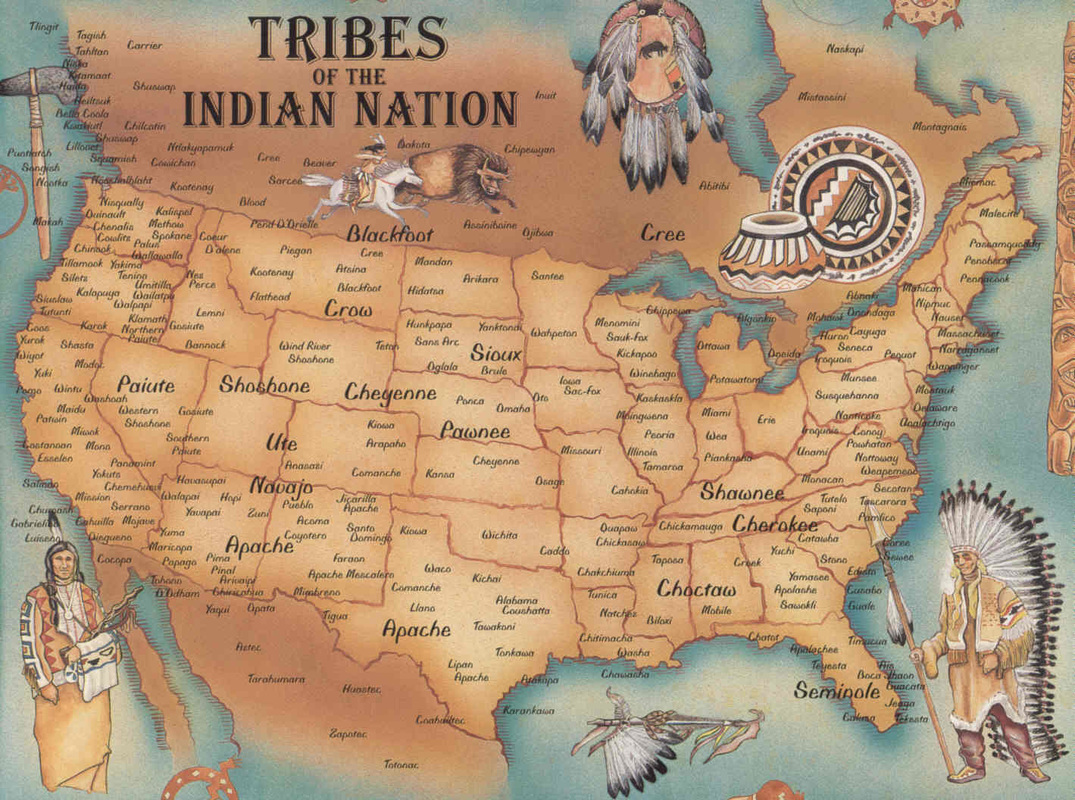

You’ll get about two dozen different Indians in this book, though most are of two tribes. Here’s what that looks like:

Oh, yeah…there’s a Frenchman too, one named Francois Antoine Larocque. He was an actual trapper that explored the same general areas as Colter, just a couple years before. He went all over and traded and even met Lewis and Clark as they were heading to the Pacific. He was never an Indian captive, though I make him one.

It’s all in the book, and I hope you’ll check it out. I had a lot of fun writing it, which you might have been able to tell – I finished the book in just a month.

Colter’s Hell will be out soon, and if you like Montana history, thrilling stories, and quite a bit of action and adventure, this is a book for you. Check it out!

John Colter’s Montana

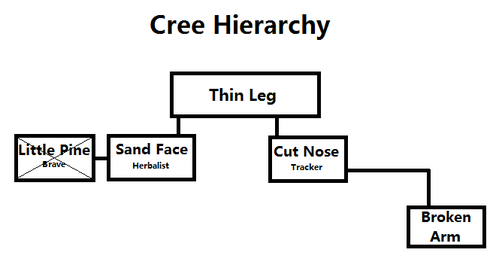

Montana was very political in 1807, and that was due to the shifting Indian alliances. There were lots of tribes in this area, many spoke different languages, and they often hated each other’s guts.

Remember, many of the tribes that came here had been pushed west by other tribes, themselves pushed by the whites. Plains tribes became nomadic, and the Blackfoot were a good example of this. No one could ride a horse or kill from it better than a Blackfoot brave.

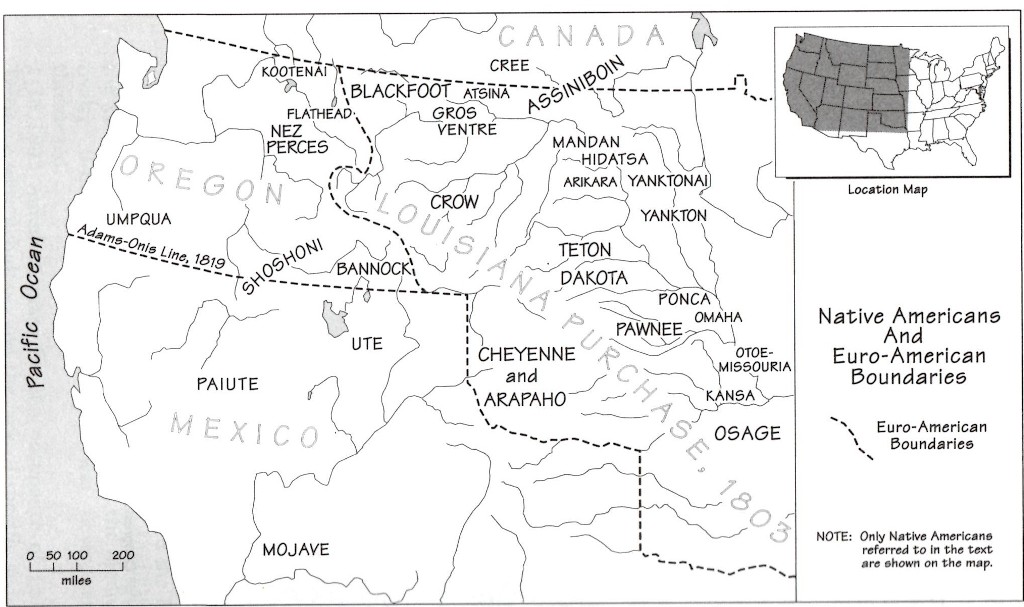

Here are some maps that show Indian territory in Montana in the early 1800s:

Montana’s Crow Indians in the early 1800s

Colter was to head up the Wind River. On the way he went through Jackson’s Hole, across the Tetons, skirted Yellowstone, and arrived back at Fort Raymond.

He journeyed extensively in the winter from October 1807 to around April 1808, and routinely did so in temperatures below freezing. The temperatures in January alone can get as low as -30 °F (-34 °C), and it’s a wonder he didn’t die from exposure.

He travelled with only a gun, a pack weighing 35 pounds, and the clothes on his back. He travelled hundreds of miles, perhaps as many as 500, through Montana and Wyoming, in areas that had never seen a white man before, and with no maps or guides to show him the way.

Here are some Montana Crow facts:

- The Crow split into the Mountain Crow and the River Crow shortly after coming to Montana around the late-1600s and early-1700s.

- The French met the Crow in 1743. In 1804 the tribe had 350 lodges and 3,500 members.

- Crow men were proud of their long hair and decorated it. Women had short hair.

- The Crow had as many as 10,000 horses by the mid-1800s. They also had hundreds of dogs.

- Nirumbee was the name for the goblin-like little people of Crow folklore. They’re also called the Little People of the Pryor Mountains.

- Old Man Coyote was the name for the Crow Creator God.

Lewis & Clark Characters in the Book

- Lewis

- Drouillard

- Joseph Field

- Reuben Field

The men had horses, and that’s why the Indians became interested in them, and why two lost their lives. Lewis got 21 horses from the Nez Perce on May 9 (Clark’s group had 49 horses on July 3). Those horses were sought by the Blackfeet, and that incident starts our story, with a fight that took place south of Birch Creek, 25 miles southeast of Browning.

After that we move ahead a year to Manuel Lisa. Some of the men that make up this storyline include:

- George Drouillard – a half-Shawnee half-French-Canadian scout.

- Sergeant Nathaniel Pryor – (1772 - 1831) - Pryor remained in the army after the L&C Expedition and was a second lieutenant until 1810. He married an Osage girl, and they had several children who were all given Indian names. He is buried at Pryor, Mayes County, Oklahoma, where a monument stands in his honor.

- Private John Potts – (1776-1810) - Potts joined Manuel Lisa's trapping party of 1807 to the upper Missouri. In 1810 he was a member of Andrew Henry's party to the Three Forks of the Missouri. Here he again met John Colter, where they were attacked by the Blackfeet, and John Potts was killed.

- Private Peter Weiser – (1781 - ?) - Between 1808 and 1810 he was on the Three Forks of the Missouri, and on the Snake River. He was killed prior to the years 1825 - 1828. The town of Weiser, and the Weiser River in Idaho, are named for him.

- Private John Collins – (? - 1823) – Collins was killed in a fight with the Arikara on June 2, 1823, an event that started the Arikara War.

- Private George Shannon – (1785 - 1836) - In 1807, he was one of the men under Ensign Nathaniel Pryor which attempted to return Chief Sheheke to his home among the Mandans. He lost his foot or a portion of his leg in the attack which occurred. He was a member of George Drouillard’s murder trial, and helped acquit the man. Shannon was elected a member of the Kentucky House of Representatives in 1820 and 1822. He was a State senator from Missouri for a time, then returned to law. He died suddenly in court at Palmyra, Missouri, in 1836, aged forty-nine, and is buried there.

- Private Pierre Cruzatte – (? - 1825 - 28) – Piloted one of the boats on the L&C Expedition even though he had one eye and was half-blind in the other. He was killed by 1825-1828.

- Private George Gibson – (? - 1809) - Gibson after the expedition, but died in St. Louis in 1809.

- Private Hugh Hall – (1772 - ?) – Captain William Clark noted that Hall drank a lot and was one of the more quarrelsome of the party. He was reported as being in St. Louis in 1809 and was still alive in 1828.

- Private Joseph Whitehouse – (1775 - ?) – Captain Clark, in his account of the members made during the years 1825-1828, lists the name, Joseph Whitehouse, without comment.

- Francois LeCompt – Half-Blood trader

- Antoine Bissonnette – Shot by Drouillard.

- Etienne Brant – Stole whiskey, slapped, and charged $162

- Benito Vasquez – Lisa’s second in command, was on Santa Fe Expedition.

- Jean Baptiste Bouche – Cantankerous man that always caused trouble

- Edward Rose – Mulatto interpreter who lived with Osage Indians

- Edward Robinson

- John Hoback

- Jacob Reznor

Those last few we don’t know anything about, save for them being on the Upper Missouri at this time. Edward Rose actually got into one helluva fight with Manuel Lisa, but we’ll save that for the next volume in this mountain man novel series.

Mountain Man Statistics

Historian LeRoy Hafen wrote a 10-volume study of the mountain men, and found that 58% of the 292 men he studied died from “old age or associated physical illnesses.” That was 134 men.

“Only 25, or 11%, of the subjects were murdered by Indians,” it’s written on furtrapper.com, “while another 7% were killed by others than Indians.”

Sickness took 16% (or 38 men) while 4.5% (or 13 men) died of “suicide, alcoholism, and miscellaneous causes.” Most mountain men died peacefully, or 77% of them.

All of that was long after Colter’s time, for Hafen puts the average date of birth for the mountain men he studied at 1805…when John Colter was already 31-years old.

Colter had been born in Virginia in 1774 and then the family moved to Kentucky around 1880. Most mountain man followed similar patterns.

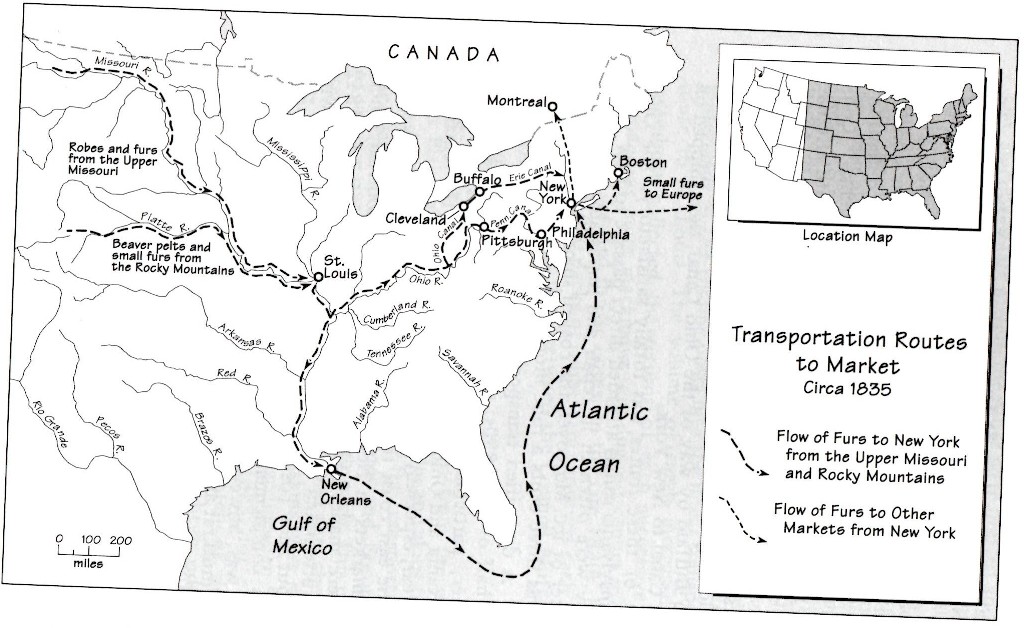

Hafen tells us that 53% of mountain men were from Canada (38 men), Missouri (34), Kentucky (31), and Virginia (29). Another 31% were foreign born, with half of those representing Canada.

You’ll get a lot more information in LeRoy Hafen’s wonderful books, which I profiled in a post called the 10 Great Mountain Man Fur Trapping Books. Check it out!

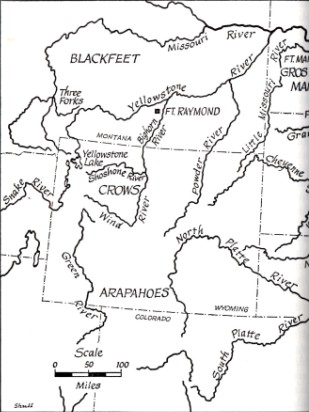

Actual Route of John Colter over the Winter of 1807-8

Since Colter made no maps, like George Drouillard was doing at the same time in other areas, it’s difficult to tell exactly where he went.

It’s surmised that he travelled near Cody, Wyoming, seeing geysers. He most likely passed through Togwotee Pass along the Continental Divide to get to Jackson Lake, and through Teton Pass to get to Pierre’s Hole in Idaho.

We know he reached the Wind River, which are the upper reaches of the Bighorn River in Wyoming. He also came across Yellowstone Lake, and the area afforded him views of more geysers and alien landscapes.

Here’s a more detailed look at each leg of the 5-month journey, one I had in an earlier post called John Colter’s 1807 Solo Trek Map

Colter reaches the Shoshone River, after having passed through the Pryor Mountains, which is a smaller range north of the Bighorn Mountains, and then skirts along their southern reaches.

Colter passes by Bighorn Lake and continues to follow the Shoshone River. He sees Heart Mountain and turns south there. After a short time he reaches the first of Yellowstone Park near modern day Cody, WY.

Colter continues moving south, skirting the Absaroka Range until he encounters a pass between them and the Owl Creek Mountains. This eventually leads him to the Wind River.

Colter passes over the Wind River and continues skirting the southern reaches of the Absaroka Range, eventually passing north of the Wind River Range.

Colter makes it to the Gros Ventre River, which he soon recognizes as an offshoot of a larger river. He keeps moving and reaches the Snake River and from there follows it as it flows north. He reaches Jackson Lake, near today’s Jackson Hole, and starts moving north, past the Teton Range to his west.

Colter heads north and passes by the small Lewis Lake before reaching the West Thumb of Yellowstone Lake. He discovers that the Yellowstone River feeds into the lake and then drains from it at the north end.

Yellowstone Falls

Colter follows the Yellowstone River as it flows north, possibly reaching the Upper Falls, though it’s doubtful. Once there he turns east and heads overland, meaning to get back to the Shoshone River. Colter then heads back west until he reaches the Clark Fork, which he’d passed by earlier.

Clark Fork

Colter heads north up the Clark Fork and then breaks off to head west overland to the Pryor Mountains when he spots the range in the distance. From there he heads north, back up to the Yellowstone and then Fort Raymond