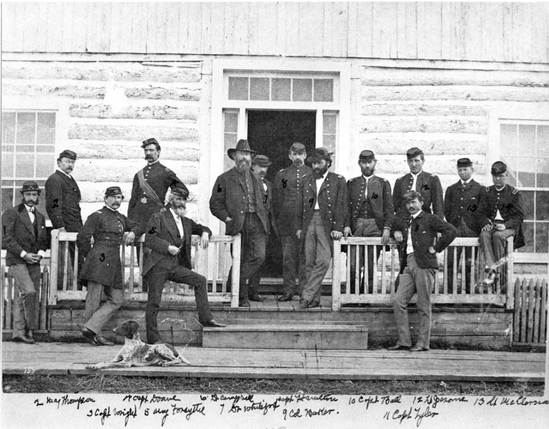

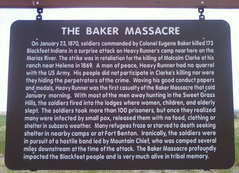

Historical Sign at Site

Historical Sign at Site

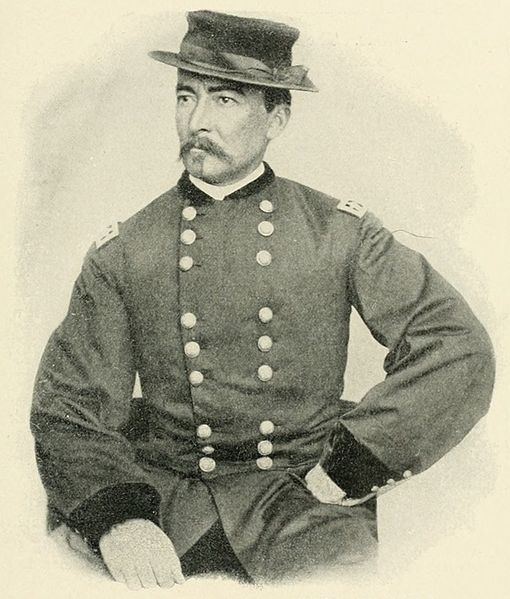

Major Eugene Baker, a man known for his fondness for alcohol, was leading his Second US Regiment cavalrymen through the snow and toward a band of Piegan Blackfeet Indians led by Mountain Chief.

He’d been ordered to do so by General Philip Sheridan, the head of the Department of the Missouri, which was the department of the US Army responsible for protecting the Great Plains. The reason? Horses.

A Horse Deal Gone Bad

Clarke wasn’t buying that for a second so he and his son tracked down Owl Child and beat the living daylights out of him. That might have settled the matter, but the beating occurred in front of other Blackfeet Indians. Owl Child had lost face and now had to regain his honor.

And so Baker found himself in the freezing snow on a cold January morning, a village full of Piegan women and children before him. He most likely took a drink and thought on what to do. His choice would prove to be a fateful one.

Montana and the Blackfeet Indians in the Mid-19th Century

To further cement that deal, which many Blackfeet felt hadn’t included them enough, Washington Territory governor Isaac Stevens travelled to them in 1855 and made a new treaty with them specifically. This treaty, called Lame Bull’s Treaty, gave both the Blackfeet and the Gros Ventre large swaths of Southwestern Montana.

By 1865, however, white settlers were encroaching on their lands. Homesteaders were flocking to the new territory of Montana for gold, and treaties were drawn up to exclude the Blackfeet from the very lands that had been given to them by Stevens, who by that time was long dead from wounds suffered at the Battle of Chantilly during the Civil War. No one cared about them, and the same thing happened again in 1868.

What’s more, John Bozeman had blazed his trail right through their lands, angering them even more. Coupled with the rising resentment of the Sioux tribes further to the east toward the US Army and white settlers and you had a real powder keg waiting to explode.

And explode it did during Red Cloud’s War, the conflict that swept through much of the area to the south of Montana Territory in those years. The US government came out victorious and many Indian tribes were left wanting. Things were coming to a boil once again.

The Piegan Blackfeet Village of Owl Child

Baker left Fort Shaw with a total of six companies, which comes out to about 200 men. And the weather they went out in was a frigid -43°F that they bore primarily at night, when they marched.

It’s easy to think the men were making good time, moving as fast as they could so as to be out in the cold for as little time as possible. And perhaps that’s the reason they stopped at the first village they came to, which wasn’t even that of Owl Child, but of Chief Heavy Runner, who had nothing at all to do with it.

So why didn’t Baker know, or why didn’t anyone tell him he was at the wrong place? There are many theories for this. Perhaps the men were cold and tired, and wanted to get back to Fort Shaw as soon as possible, and if that meant attacking the first Indian village they came to regardless if it was the right one, then so be it.

One story has it that Baker was warned, most likely by his half-Mandan guide Joseph Kipp, but he was suspicious and mistrustful of the man, and even threatened to shoot him. And it could very well have been that Baker was drunk and intent upon seeing the job through no matter what. It was common knowledge that Baker was a drinker, but then many in the army at that time drank.

The Aftermath of the Massacre

And the people of Montana couldn’t have been happier. On February 10, 1870, The Bozeman Pick and Plow newspaper thanked the soldiers for braving the inclement weather and the “deserved though terrible punishment inflicted upon them.” (Schontzler)

Not all voices were singing the Army’s praises, however, and it was actually from within the army that the first calls questioning the whole affair originated.

General Alfred Sully, the Interior Department superintendent for Indian affairs, wondered why there were so few men of fighting age that’d been killed. Lieutenant William Pease, who was then the Blackfeet agent for Indian affairs, told him that just thirty-three men had been killed. He was also quick to point out that ninety women and fifty-five babies were slaughtered that day.

Somehow that information was leaked to the press in Washington and things really went downhill. By March the Chicago Tribune was calling the event a “most disgraceful butchery,” even while Phil Sheridan defended the actions of Baker. He wasn’t alone, either, as The Helena Daily Herald likened Baker’s actions to hunting down wolves.

The support wasn’t enough, however, and Baker was feeling the pressure. He made a new report that quadrupled the number of men killed that day in January, from thirty-three to around 140. And it worked. Washington and the U.S. Army covered the massacre up and it was largely forgotten.

Eugene M. Baker was brought up on charges of drunkenness at a later date, and he’d eventually die in 1885 from cirrhosis of the liver at the age of 48.

For the Piegan Blackfeet it was a different story. However much they may have wanted to fight, they couldn’t. Already their numbers had been drastically decreased by smallpox.

So what ultimately happened? The papers applauded the version they wanted to accept instead of reporting the facts; the U.S. Army expunged their own records of the event fearing more public backlash; and business went on as usual and like nothing had happened. Overall the Marias Massacre, or Baker Massacre as it’s sometimes called, is a stain on American history and a shame for Montana.

Montana’s Indian Tribes: The Blackfeet

Montana’s Indian Tribes in the 1850s and 1860s

Ewers, John C. The Blackfeet: Raiders on the Northwestern Plains. The University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 1958. p 238-50.

Fifer, Barbara. Montana Battlefields, 1806-1877: Native Americans and the U.S. Army at War. Farcountry Press: Helena, 2005. p 31-9.

Schultz, James Willard Keith and Seele, C. Blackfeet and Buffalo: Memories of Life Among the Indians. The University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 1981. p 282-306.

Schontzler, Gail. (2012, January 5) Blackfeet remember Montana’s greatest Indian massacre. Bozeman Daily Chronicle. Retrieved: http://www.bozemandailychronicle.com/news/sunday/article_daca1094-4484-11e1-918e-001871e3ce6c.html

Welch, James and Stekler, Paul. Killing Custer: The Battle of the Little Bighorn and the Fate of the Plains Indians. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.: New York, 1994. p 25-30.