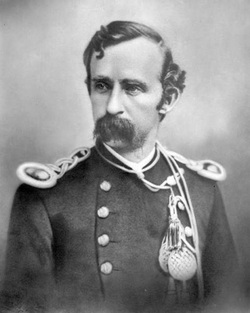

George Armstrong Custer, 1875

George Armstrong Custer, 1875

To do that Custer was assigned between 1,000 and 1,200 men. Accompanying them would be 110 wagons carrying two months worth of food. Horses were numerous and the expedition also brought along its own cattle.

Accompanying the expedition as well was English photographer William H. Illingworth. Captain William Ludlow had chosen Illingworth to document the expedition at a cost of $30 a month, which resulted in the US Army acquiring 70 photographic plates and historians wonderful pictures to show.

The group set out from Fort Abraham Lincoln in the Dakota Territory, today’s Bismarck, North Dakota.

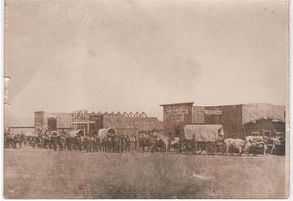

Fort Abraham Lincoln

George and Libbie at the fort, April, 1874

George and Libbie at the fort, April, 1874

For nearly 200 years the Mandans had lived in a village called On-A-Slant, Miti-ba-wa-esh in Mandan, until smallpox came in 1781. It devastated them and they were forced to move north to join the Hidatsa along the Knife River.

Fort Abraham Lincoln was on the west banks of the Missouri and was built by Colonel Daniel Huston, Jr. and his two companies of the 6th U.S. Infantry.

The fort had originally been called Fort McKeen when it’d been finished in June, 1872, named after Colonel Henry Boyd McKean, who’d been killed at the Battle of Cold Harbor on June 3, 1864. The fort was renamed Fort Abraham Lincoln in November, 1872.

Custer and his wife, Libbie, lived at the fort from 1873 until July, 1876. The first home built at the fort was for Custer, completed in the summer of 1873. It didn’t last too long, however, burning down the following February. Besides the Custers, 500 soldiers called the fort home.

Setting Off for the Black Hills

Freight Train entering Custer, South Dakota, 1876

Freight Train entering Custer, South Dakota, 1876

They didn’t have much time, but that didn’t stop Custer from dilly-dallying. He made but 4 or 5 miles a day and then stopped at Harney Peak, which had been named after General William S. Harney, who’d always been a voice of peace for the Indians.

Harney Peak

Harney Peak

They ascended on horseback and dismounted when they reached the top. Custer, however, kicked his horse up further before getting down, allowing him the honor of being the first. Accompanying engineer W.H. Wood called the move “cruel.”

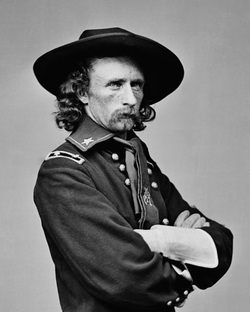

But that’s just how Custer was. If he wasn’t your best friend he was rattling your nerves, and often both at the same time. People who loved him hated him and it was also hard not to like him when he was your enemy.

He had qualities that other men gravitated toward – confidence bordering on arrogance, good cheer that could turn nasty, and a headstrongness that allowed him to challenge, push, and prod until he got his way. And more often than not, he got his way.

George Armstrong Custer

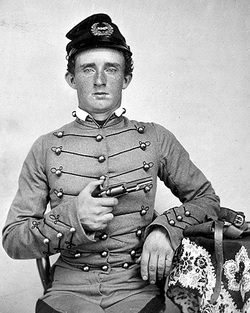

Cadet Custer, 1859

Cadet Custer, 1859

Custer was rushed through the military academy, something that happened to many recruits that year in the build-up to war. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Cavalry. He ran messages at the First Battle of Bull Run and then served in the Peninsula Campaign of 1862.

By the time Gettysburg came along Custer had been promoted to brigadier general, and at the young age of 23. By 1864 Custer was under the command of Major General Philip Sheridan as they descended into the Shenandoah Valley to take on Confederate Lieutenant General Jubal Early. After that it was just the Siege of Petersburg for the winter and then on to Appomattox the following spring.

After the war Custer was appointed to a post in Texas where he oversaw the transition of the soldiers from the army to civilian life. He was offered a job commanding forces for Benito Juarez’ army in Mexico, and seriously considered it enough to ask for a one-year leave of absence to pursue it (the pay was $10,000 in gold, after all). Secretary of State William H. Seward, however, was against having U.S. soldiers overseeing foreign troops, so nixed the idea.

Custer, May 23, 1865

Custer, May 23, 1865

In 1867 he began fighting against the Indians in Major General Winfield Scott Hancock’s efforts against the Cheyenne. After that campaign he took off to see his wife, and was caught. Court-martialed for being AWOL, Custer was suspended from duty for a year, although Sheridan intervened and got him reinstated by the end of 1868 so he could have him in his Indian campaign.

That November Custer led his forces to the Cheyenne encampment of Black Kettle, which resulted in the Battle of the Washita River on November 27. In that fight Custer claimed to have killed 103 Indian warriors, though the Cheyenne claimed it was closer to 30, 19 of them women and children.

Custer did take 53 women and children prisoner, and also managed to capture 875 horses. Such a good show led the battle to be labeled the first major victory for the U.S. Army in what would become the Southern Plains War.

Custer Arrives in the Black Hills

Grizzly Bear Custer shot on August 7, 1874

Grizzly Bear Custer shot on August 7, 1874

The Indians in the area treated Custer and his men kindly, and the kindness was returned. There was great hunting to be had as well, as Custer found out firsthand on August 7 when he bagged a large grizzly, something he always said was the best hunting shot he’d ever made.

There were many civilian hanger’s-on with Custer, and they quickly set about looking for gold, even scouting ahead of the army. It didn’t matter that they didn’t’ really find any, they caused a fair amount of gold fever nonetheless.

No one really knows who found the first traces of gold. Each night when men would finish their dinners they’d grab a pan and head to a creek. One man, William McKay, kept a diary and made a notation one night while camping at Custer Park. He figured he found “one and half to two cents.”

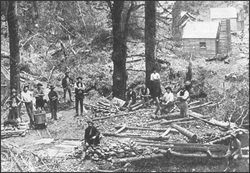

Black Hills Gold Miners, 1874

Black Hills Gold Miners, 1874

On August 1, a day before Custer settled in Agnes Park, they declared that a miner could be making $150 a day in the Black Hills.

By August 15 Custer had written to the Assistant Adjutant General of the Department of Dakota telling him he had “no doubt” there were riches to be had. A scout named Charley Reynolds carried the letter to Fort Laramie where telegraph lines carried the message back east. It wasn’t long before a gold rush took place.

Since all these whites were flocking into areas promised to the Sioux with the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, it’s no wonder the tribes were a little angry. And their anger at Custer would only grow, culminating in the battle that cost him and his two younger brothers their lives less than a year later at the Battle of Little Bighorn on June 25-26, 1876.

Connell, Evan S. Son of the Morning Star. North Point Press: San Francisco, 1984. p 237–238.

Hatch, Thom. The Custer Companion: A Comprehensive Guide to the Life of George Armstrong Custer and the Plains Indian Wars. Stackpole Books: Mechanicsburg, 2002. p 147-8.

Hutton, Paul Andrew. Phil Sheridan and His Army. University of Nebraska Press: Norman, 1985. p 308-20.

Jackson, Donald. Custer’s Gold: The United States Cavalry Expedition of 1874. Yale University Press: New Haven, 1966.