Fort Missoula in WWII

Fort Missoula in WWII

The US had started seizing Italian ships and their crews even before Pearl Harbor.

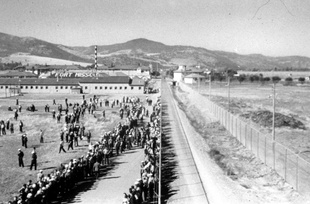

Most of these incidents took place in the Panama Canal, with the belief that the ships were heading to the West Coast to cause trouble, or across the Pacific to aid the Japanese. A total of 1,200 of these sailors were sent to the internment camp at Missoula starting in 1941.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor they noticed that their treatment got worse, though many were allowed out into the community to help with worker shortages, and even put on musical shows for locals.

Also at Fort Missoula were Japanese prisoners, mostly old men. On February 19, 1942, Executive order 9066 had created the nation’s Japanese internment camps. They would go on to confine 110,000 Japanese Americans, 75,000 of whom were American citizens.

About 1,000 Japanese were brought to Fort Missoula in March 1942. The Japanese prisoners at Fort Missoula were treated more harshly, more like “aliens.” They also had to undergo more questioning.

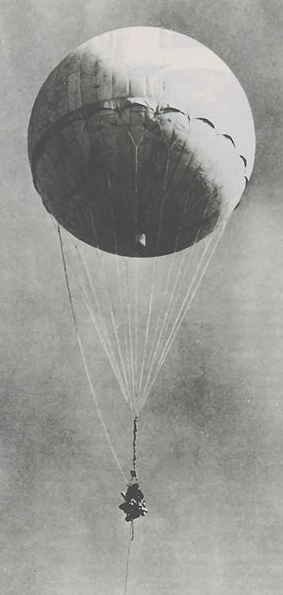

A big reason for this was the fear of a Japanese attack on the West Coast, particularly with balloons. It might seem funny now, but hot air balloon attacks were viewed as a real threat. Even in Montana this was causing anxiety.

The Japanese had Project Fu-go, which sent out “balloon bombs” to start forest fires.

The aim was to disrupt the American war effort as much as possible, and in Montana it would have done more than that. With so many men out of state, out of control forest fires were the last thing anyone wanted to deal with.

Around 30 of the Japanese balloon bombs landed in Montana, though none ever caused any damage or injury. In May 1945, however, six people in Oregon were killed when they found one of the bombs in the forest and it blew up on them.

Montana’s Mike Mansfield spoke out against interring the Japanese citizens of America. It did little good.

The number of Japanese imprisoned in Montana increased over the years, so much so that the state made a request to the feds that 4,500 of the Japanese be used in the sugar beet fields.

In addition to those rounded up in America and the Panama Canal, enemy combatants were also brought to America as POWs.

A total of 425,000 Axis POWs served their detention on American soil during the war. Besides the internment camps in Missoula, there were also camps in Billings, Forsyth, Glendive, Miles City and Sidney.

POWs working on Montana farms or involved in other labor were paid $0.80 a day, money they largely used “to buy cigarettes, candy, razor blades, soap, and towels.” This was far better than the conscientious objectors at the state’s Civilian Public Service camps, who were paid nothing.

While it was clear that only individuals from belligerent nations would have their rights suspended (unless you were Japanese or believed in peace), it was a clear sign to everyone else that the government wasn’t playing by the normal rules.

That often meant others didn’t have to either. If you were in Montana and Japanese and you weren’t interred, you likely lost your job instead.

Such was the fate of Tom Oiye of Three Forks. The Trident cement plant laid him off, “even though his son was serving as a U.S. Army combat soldier.”

All of the prisoners were gone from Fort Missoula by March 1944. Nine months later in December the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Japanese internment camps were illegal.

In 1988 Congress gave every one of the 62,000 surviving Japanese detainees $20,000 tax free. This cost the feds $1.25 billion, a small price to pay for getting rid of their shame.

Feds and Farmers