Jedediah Smith

Jedediah Smith It was in Pennsylvania that Jedediah Smith met the man that would become his mentor, Dr. Titus G.V. Simons. This physician to pioneers gave Smith a copy of the 1814 Journal of Lewis and Clark. Smith was so taken by the work that he supposedly carried it everywhere he went in the West.

Jedediah Smith was known for having basic communication skills with many different Indian tribes later in life, and it’s no wonder why. While growing up around Jericho, Smith routinely made contact with the Delaware, Mohican, Mohawk, and Wyandot Indians. He also spent a lot of time traipsing about the woods, something that would come in useful for him later in life in the vast wildernesses of the Rocky Mountains.

Jedediah Smith was also acquainted with another hero of American folklore, John Chapman, better known as “Johnny Appleseed.” Chapman and the Smith family owned adjacent properties in Green and Wayne Townships in Ohio. Chapman had been born in Massachusetts, but moved out west to the Ohio frontier in 1800, both to spread his form of Swedenborgian Christianity, which extolled humility and pacifism, and to plant apple trees. Simons also owned adjacent property to Chapman, so it’s a good guess that some of Chapman’s teachings rubbed off on a young Jedediah Smith.

Heading West

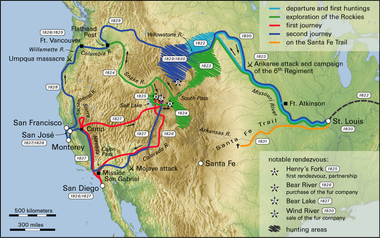

Smith's areas of exploration

Smith's areas of exploration He traveled with Daniel Moore’s expedition to Fort Henry, learning to trap and hunt buffalo on the way upriver. And it was on that expedition that disaster struck, at least for Ashley. While rounding a bend, the keelboat’s mast became entangled in some trees and capsized. Men and materials were tossed about, and while no lives were lost, $10,000 of cargo was.

Moore quickly headed off to inform Ashley, while the others had to sit and wait beside the river. Such a rocky start could have dashed anyone’s hopes, but not Ashley’s. He quickly outfitted another expedition, and to make sure that no further incidents occurred, led it himself, reaching the stranded men a month later.

Ashley reached the Mandan villages in September and split his party, sending half up the Missouri while he and a group went overland toward the Yellowstone River. Jedediah Smith joined the overland route, and they reached Fort Henry, spending the months winter months hunting and trapping around the Musselshell. Ashley had left before the rivers froze, meaning to get back to St. Louis to sell some furs, no doubt hoping to wipe that earlier loss off the books as soon as possible.

The Arikara War

Henry Leavenworth

Henry Leavenworth Things worked out alright at first. Trading was slow, but over two days Ashley was able to get what he wanted. A large wind storm began just as the men were about to head back to the river, making navigation all but impossible. They were forced to stay another night on the village’s outskirts, and most men were certain that an attack would come. And come it did, on the morning of June 2nd, around 3:30 AM.

Forty of Ashley’s men were sleeping near the river’s beach, and they were awoken by someone shouting that the Arikaras were attacking. Smith became pinned down on the beach, while all around him his companions were dying. He put up a brave fight, but his position made his efforts largely futile. By the time the men could get out of there, thirteen had been killed, as well as all of the horses that Henry had requested. Ashley decided to send for Henry, ordering him to come down the Yellowstone River at once, and he chose Smith to deliver the message. He and an unnamed Canadian headed upriver and managed to bring Henry and his men back down and past the Arikaras without being noticed.

Ashley headed to Fort Atkinson to see if you could get something done about the intolerable Indian situation blocking him from making a profit on the rivers. He solicited the help of Colonel Henry Leavenworth, who put together 250 men for an attack on the villages. Together with Joshua Pilcher’s men from the Missouri River Fur Company, and another 700 Sioux Indians that had it out for the Arikara, the total force exceeded a thousand men.

Two months after the attack that had started it all, Henry Leavenworth ordered his “Missouri Legion,” as Pilcher called it, to the villages. The first attack came on August 10th, but it had little effect other than killing the Arikara leader, Grey Eyes. By that evening the Sioux Indians were making their displeasure at the pace of the attacks known, and they departed. Now back down to little more than 300 men, Leavenworth decided to call the whole thing off, and quickly made a peace agreement on August 11th. Most of the mountain men were furious, none more so than Pilcher, who would later write off a nasty letter to the St. Louis Enquirer about the whole affair.

And the Arikara War, as the incident came to be known, probably did more harm than good. Far from being cowed at American might, the Arikara and other Indians were emboldened. They had fought and held their ground against men that were coming into their territory and taking whatever it was they wanted. It also showed that the federal government’s Indian policy was outdated and needed to change. There were no real directives from Washington involved with Leavenworth’s decision to attack the Arikara, and perhaps he never should have. All of the mountain men were in direct violation of federal interstate commerce laws by even being in the area and trading in the first place. Of course this was never discussed when the beaver pelts were being bought and sold, especially with many in the nation’s capital wearing fur-lined hats. What is clear is that the attack only made further Arikara attacks more likely, and the mountain men’s lives more dangerous.

Scarred For Life

Mother Grizzly with cubs

Mother Grizzly with cubs The attack occurred in full-sight of Smith’s companions, and they reported that the bear tackled Smith to the ground, ripping open his side with its massive claws. At one point, Smith’s head even became wedged between the bear’s jaws. One of the men that rushed up when the attack occurred managed to get off a good shot with his rifle, killing the bear. When the rest of Smith’s companions rushed to him, they found him in bad shape.

While the wounds that covered his body were severe, it was the gruesome damage done to Smith’s face that really shocked them. The bear had ripped Smith’s ear and scalp nearly clean off, and Jim Clyman had to sew them back on. After cleaning his wounds with water and binding up his broken ribs, Smith was able to rest, though the scars that now covered the right side of his face would mar his good looks for the rest of his days, and he’d usually grow his hair long to cover the right side of his face.

Exploring and Profiting

Green River in Wyoming

Green River in Wyoming The Indians were able to relay that the best route lay through the Continental Divide between the Wind River Range and Great Divide Basin. The pass became known as South Pass, and Smith and his men managed to get through safely to Utah’s Green River. While the pass had been known before, having been discovered by whites and used extensively from 1811-1813, Smith’s use of the trail brought it back into the consciousness of Americans, especially the fur trappers and mountain men that needed it most.

Between 1824 and 1825 Smith spent most of his time trapping along the Bear, Clark’s Fork, Green, and Snake Rivers. He did so well that he was able to become a partner with William H. Ashley when Andrew Henry decided to retire. And he was probably ready to partner up and have a go at directing affairs and not being such a direct player in them.

Heading to California

By 1829 Smith was on a roll. His firm of Smith, Jackson, and Sublette was making good money, and in 1830 the men sold out to Tom Fitzpatrick, Milton Sublette, Henry Fraeb, John Baptiste Gervais, and Jim Bridger. Smith let them form the Rocky Mountain Fur Company while he considered retirement from the fur trade altogether, and in 1830 he did just that.

While leading a group of supply wagons for the Rocky Mountain Fur Company in late May, 1831, Smith went for water and never came back. The party was travelling on the Santé Fe Trail, an area well-known for Comanche Indians. The party continued on to Santa Fe, where several of the members of the group discovered many of Smith’s possessions being sold by a Mexican merchant. When pressed, the merchant said he had gotten them from Comanche Indians. Jedediah Smith died on May 27, 1831. He was just 32 years old.

Barbour, Barton H. Jedediah Smith: No Ordinary Mountain Man. The University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 2009. p 16-55.

Morgan, Dale L. Jedediah Smith and the Opening of the West. Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1964. p 110-114.