Rough and Tumble with a Grizzly

Rough and Tumble with a Grizzly

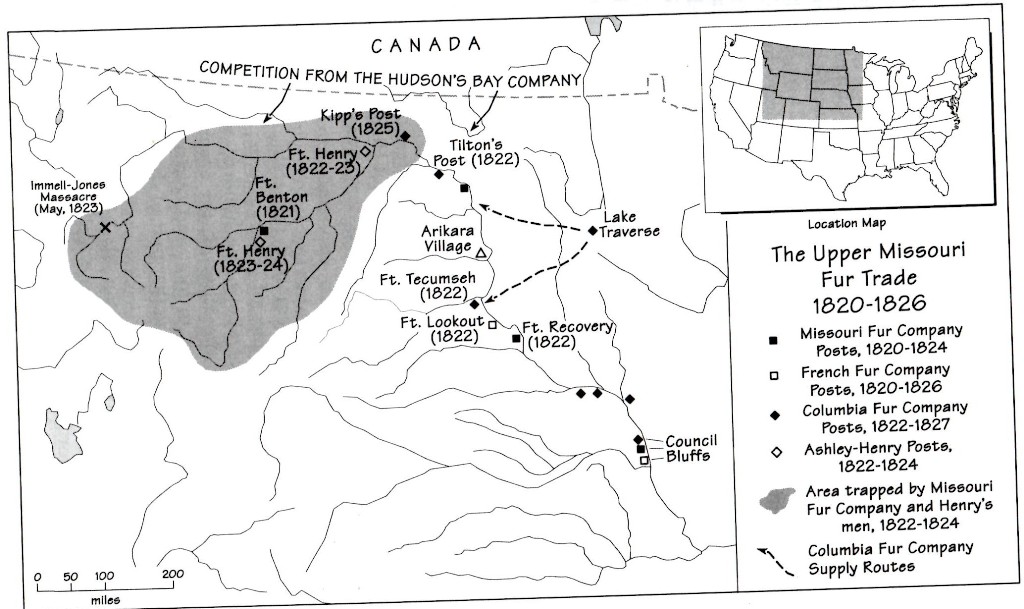

At one point Hugh Glass may have been a sailor, and was either working with or forced to flee the French pirate Jean Lafitte, who operated in the Gulf of Mexico.

That would have put Glass in the area sometime between the end of the War of 1812 and around the time the US Navy got serious about removing Lafitte in 1821, if it’s even true at all.

What we do know is that Hugh Glass gets his first real notice by those recording history when he joined the Ashley expedition of 1823, and that he was present when the group came under attack from the Arikara Indians, taking a wound in the leg. The men continued upriver, led by Andrew Henry.

The Grizzly

Grizzly Bear

Grizzly Bear

It’s not quite clear how he came across the animal, but there are two accepted possibilities. First, Moses Harris, the same African American that almost had to be dragged from the wilderness by James Beckwourth, got lost while out looking for berries.

Glass headed out to look for him, and stumbled upon a Grizzly instead. Second, it could also have been that Glass just wanted to head out on his own, the scouts and other men be damned. Mountain men were strong willed, and Hugh Glass more so than others.

The attack occurred in August, 1823. Glass was 100 yards from the beast when he took aim and shot it, but he might as well have been shooting at a freight train for all the good it did him.

Sensing that he was on the losing end of this proposition, Glass turned to run, but tripped and fell to the ground. By the time he looked up, the bear was towering over him. He grabbed his pistol, got off a shot, but had it swatted away a second later.

The bear dug in with her claws, and Glass was ripped and shredded to the bone in several places. He stabbed with his knife as best he could, but didn’t seem to be making much headway.

Finally he let the blade drop from his hand and went limp. The bear did the same, dying atop him from the gunshot wounds and at least twenty knife wounds.

Left for Dead

1823 Route of Hugh Glass

1823 Route of Hugh Glass

nd terrible they were; nearly every area of Glass’s body had been ripped open in at least one spot, from his legs to his arms to the massive wound in his throat that appeared to make breathing all but impossible. The men took stock and counted fifteen major wounds.

The minutes stretched into hours, and soon night was upon them, and Andrew Henry was in a quandary. He didn’t want to leave Glass to die unattended, but he didn’t want to stay in the area for fear of another Arikara attack.

And the men in Fort Henry further upriver were waiting on him too; each hour that Henry sat there on that riverbank was another hour the men in the fort would have to wait for their supplies, and the peace of mind that having more men in Indian country could bring.

In the end he compromised, and solicited volunteers to stick it out with Glass for as long as it took for the man to succumb to his wounds.

It must have been clear to him that no one wanted to risk sitting around the area, or perhaps his conscious was nagging at him. Either way, Henry offered money to those that would stay with the dying Glass. Each man was encouraged to contribute, and all did, to the tune of $1.

Whether they actually contributed actual money or just promissory notes, $80 ended up being collected, and two men quickly jumped at the offer, John F. Fitzgerald and the 18-year old Jim Bridger. After all, $40 was half the money they could make in a year, and the earlier dangers of the day quickly faded from memory at the prospect of all that money for just a few hours of work.

Henry set out the next morning, and came under further Indian attacks, losing two men. A few days later they made it to the fort. Fitzgerald and Bridger meanwhile did the best they could with what they had, which wasn’t much.

They used cold creek water on Glass’s wounds, and fed him soup. They didn’t hunt, not wanting to fire their rifles, and fires weren’t built either. Both men were still fearful of Arikara attacks, and that fear no doubt increased every hour they had to stay with Glass.

By the third day Fitzgerald claimed to have seen signs of Indians, and he told Bridger he meant to go. Bridger agreed, not wanting to go, but not wanting to stay alone either.

Fitzgerald reckoned he’d need proof that Glass had died, the better to collect the reward money with after all, so the men took all of Glass’s possessions; his rifle, knife, and other gear. Glass was barely conscious.

Just a few days later, Fitzgerald and Bridger came traipsing into Fort Henry. They informed Henry that Glass had taken five days to die, and that they had given him a proper burial in the end.

They presented Glass’s rifle, knife, and other gear to Henry, and the matter was settled; another mountain man had died because of Indian attacks, something that occurred with frequent regularity.

From the Dead

Shepherdia argentea, Buffalo berries

Shepherdia argentea, Buffalo berries

Glass didn’t earn the reputation as having escaped from pirates through a lack of resourcefulness, and he quickly weighed his options. He was beside a small creek, and over it hung a wild cherry tree.

Buffalo berries were also growing about the area, but the final reward may have been what was lying beneath him. Perhaps not wanting to dig through a dying man’s clothes, Fitzgerald and Bridger had left Glass’s wallet. Inside was a thin razor, which Glass could fashion into a knife. They may not have been much, but they bolstered Glass’s confidence in his ability to survive.

For ten days he lay beside the creek, gaining his strength back from the cool flowing water, and the sour buffalo berries.

At one point a rattlesnake slithered up beside him, perhaps looking for a place to lounge after sating itself on a meal by the creek. Glass killed the thing with a stone, and used his razor to get at the meat. It may not have been the best meal, but it went a long way in rejuvenating him.

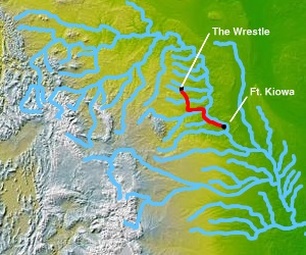

He decided to walk himself out of there, even though he could barely stand. Fort Kiowa lay 350 miles away, so it’s a wonder he thought he could make the trek at all.

The going was slow, but he didn’t have to go too far before stumbling upon a pack of wolves downing a buffalo. To scare them off, Glass used his razor as a flint and started a grassfire.

For two more days Glass stayed put, this time dining on raw buffalo meat, which he probably found as a great improvement over the sour buffalo berries and snake he had eaten for ten days beside the creek.

Accounts differ as to how he did it, but what is known is that Hugh Glass arrived at Fort Kiowa after his ordeal. He could have walked the whole way, perhaps starting with one mile, then five, before working his way up to ten each day.

Another account has him being found by a group of Sioux Indians coming up the Missouri, who then took him to the fort. Whatever his pace or method, he made it, much to the surprise of everyone.

And there was Jim Bridger, sitting in the fort worrying like crazy when Glass walked in. The haggard mountain man recounted his story of survival, never once looking Bridger’s way.

Finally he walked up to the man who was barely more than a boy and said that he forgave him. He asked about Fitzgerald and was told he’d headed downriver to Fort Atkinson.

By the time that Hugh Glass had gotten to where Bridger was, he had rowed upstream 300 miles and walked another 550. He’d been chased by Indians along the way and travelled through some of the worst weather the Rockies could throw at him.

Revenge was a strong motivator for Hugh Glass, but in the end he decided to let the whole thing go. Perhaps the look on Bridger’s face was all the revenge he needed by that point.

Upriver Again

It could have been that he wanted to get back with the men he had been with, his companions and friends of the Ashley expedition, or he could have just wanted more adventure. They left on October 10, 1823, one of the few definitive dates in Glass’s life.

There was nothing eventful about the six-week journey to the outskirts of the Mandan villages, except that Fitzgerald was going down the river when Glass was going back up. The two passed one another, but they weren’t aware of it.

Just before the party was to reach the Mandan villages, two things happened. First, Toussaint Charbonneau quit flat out. He had a bad feeling, and his “medicine” told him so. He would travel the rest of the way by land, letting his companions keep to the waterways. Second, just 10 miles from the villages, Glass got out of the boat and went ashore to hunt. It was the last he’d see of his companions again.

There was only a bend in the river, wide enough that you couldn’t see around it, and Glass thought he could bag a few animals and meet up with the boat as it finally came around the wide turn. Instead he ran into more Arikara Indians, the last thing he needed.

He was in no shape to be running, especially with wounds still tender and ready to break open at the slightest exertion. But he had little choice; the party was intent on his blood, and he ran as fast as he could.

His luck proved strong once again, for a lone Mandan Indian riding by caught site of the race, and for whatever reason, perhaps feeling the odds too stacked against the white man, or because he didn’t much like the Arikara, who may have torched several Mandan villages, he rode by and hoisted Glass up onto his horse and rode him to Tilton’s Fort, which was owned by the Columbia Fur Company.

Charbonneau was there, but no members of Langevin’s crew made it, and everyone figured the Arikara had slaughtered them and taken off with the goods.

Glass wasn’t one to sit around, and he didn’t expect any further Indian attacks, didn’t care if they did occur, or just thought himself invincible, for he set out alone from the fort toward the Yellowstone River and Fort Henry.

It took him two weeks to get there, and he found the place abandoned. Andrew Henry had given up on any further trapping near Three Forks after the most recent spate of Indian attacks, so the fort was no longer needed.

Henry most likely left a note as to where he was going, for Hugh Glass set out for the Powder River, making it as far as he could that late in the season before the rapids became too rough, and then went overland.

He ran into some Crow Indians, got some horses from them, and then ran into a group of mountain men, Jedediah Smith with them. He reached Henry’s new post on the mouth of the Bighorn River toward the end of December.

Another Close Call

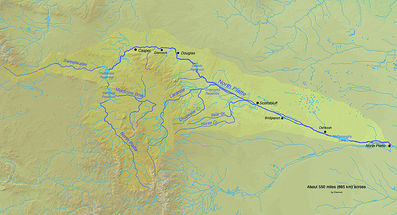

Map of North Platte River

Map of North Platte River

He had with him four companions: an E. More, A. Chapman, someone named Dutton, and another man named Marsh.

he men walked overland until they came to the North Platte River and built a boat. They went down as far as the Laramie River before they spotted any Indians, these peaceable Pawnees.

The men were urged to come ashore, and so comfortable were they at the sight and reception of the Indians that all but Dutton left their guns in the boat. The Indians treated them like kings and laid out a great feast. Something seemed amiss, and one of the men said so.

Glass shouted out that they were in fact Arikaras, and the men didn’t waste time getting back to their boat. Their guns were gone, however, and it soon became every man for himself when the Indians began whooping in delight at the white men’s peril.

Dutton made it away, as none of the Indians wanted to risk getting shot, especially when there was such easier prey before them. Marsh was a fast runner, and managed to evade his pursuers. Somehow Glass made it up some rocks and remained hidden.

He watched in horror as both Chapman and More were killed, and stayed low until dark, when the Indians called it a night. He set out on another long walk, and met up with another band of Sioux Indians who accompanied him to Fort Kiowa. From there he descended the river to Council Bluffs, where he was reunited with both Dutton and More.

By that time it was June, and Hugh Glass learned that Fitzgerald was in town. Unfortunately for Glass, Fitzgerald had renounced the life of a mountain man for that of a soldier, and was now serving as a private in the Sixth Infantry. He couldn’t have his man, but at least he could get new gear, including his rifle, from Colonel Leavenworth. And at that point Glass decided to leave the Rocky Mountains for a time.

Hugh’s Luck Runs Out

The story says that Glass was around Fort Cass on the Yellowstone River during the winter of 1832-3. Glass and two companions were hunting bears when a party of thirty Arikara Indians descended upon them. However the fight went we can’t be sure, but it’s hard to believe Glass not fighting for all he was worth, even taking down an Indian or two, perhaps even several.

Gardner and his men were in the area when the Indians came up with the intention of stealing their horses. Gardner was wise to their act, however, and had several of the Indians seized. On one of them they found Glass’s old rifle, and another his knife.

Hugh Glass’s luck had finally run out. He was 53 years old.

Morgan, Dale L. Jedediah Smith and the Opening of the West. Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1964. p 96-109.

Myers, John Meyers. The Saga of Hugh Glass: Pirate, Pawnee, and Mountain Man. Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1963.

Vestal, Stanley. Jim Bridger: Mountain Man. Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1946. p 40-56

Leslie, Edward E. Desperate Journeys, Abandoned Souls: True Stories of Castaways and other Survivors. Sterling Seagrave: New York, 1988. p 265-288.

Mayo, Matthew P. Cowboys, Mountain Men & Grizzly Bears: Fifty of the Grittiest Moments in the History of the Wild West. Globe Pequot Press: Guilford, 2009. p 21-26.

Chittenden, Hiram Martin. The American Fur Trade of the Far West [Vol 2]. University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1986. p 682-96.