“One week from today, on July 1, Last Best News will be suspending operations.”

That was the news today from Last Best News.

As you probably know, this is a political/news blog that’s been operating out of Billings since 2014.

And now it’s done.

This leaves us with the following:

- Reptile Dysfunction (Missoula)

- Big Sky Words (Missoula)

- Missoula Current (Missoula)

- Flathead Memo (Kalispell)

- Montana Post (Helena)

- MT Cowgirl (Helena)

- The Western Word (Great Falls)

There might be other Montana political news blogs, but if so, I don’t visit them…or even know they exist.

Before today we had 8 (9 this spring before we lost Logicosity), and now we’re down to 7.

It’s more than that, though.

- Last winter we had NBC Montana news stations taken over by a large corporation called Sinclair Broadcasting.

- For years now, Lee Enterprises has owned all of the major Montana daily newspapers…and their coverage has fallen off considerably due to their falling stock prices (which requires them to lay off reporters so the company executives can continue to reap high pay and bonuses).

- 2 years ago we lost a great investigative journalist, James DeHaven.

- 2 years ago we lost another great investigative journalist, John Adams.

- 3 years ago we lost two great reporters (though one of them thankfully moved over to MTN).

So it’s been a steady decline for Montana news readers for years now. This is Montana history repeating itself. We’ll get into this at the end of this post.

The Last Best News ‘retirement’ post has over 650 likes so far.

That’s one of the things you noticed about Last Best News – they got a lot of likes on Facebook.

Alas, likes don’t translate into staying power.

Sure, likes give you a sense of your popularity and community support. They also give you a false sense of your staying power.

Last Best News routinely got the social media support, yet in the end, that wasn’t enough.

It came down to the money.

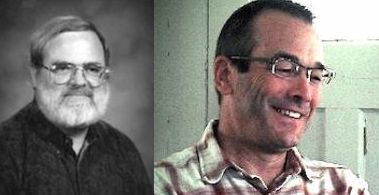

Ed Kemmick and David Crisp just weren’t making enough money from the site, so they’re quitting.

"I’m still hoping that someone will step up in the coming months and either revive Last Best News or start an entirely new online newspaper,” the site wrote today.

I highly doubt that will happen.

While Last Best News started off as a passion project, it quickly became a profit-driving venture.

Each year, Kemmick and Crisp had fundraisers for their site.

They did this so they could pay themselves.

Besides the Missoula Current, this was the only blog that felt it needed to make money off of its reporting.

So why are Crisp and Kemmick quitting? They tell us:

- “I finally grew tired of the hundred and one things involved in running an online publication”

- “I had been a wage slave for almost 35 years when I started Last Best News, so I never had a reason to learn anything about accounting, budgeting, ad sales, marketing, social media promotion and web site creation and maintenance.”

- “I had a lot of good ideas for improving and expanding Last Best News, but all of them involved at least several more years of the kind of slogging that was becoming more and more onerous, what with those thoughts of freedom rolling around in my head. I have always valued time over money, and in the end that was the deciding factor. I wanted time.”

For those paying attention, the writing was on the wall months ago.

This was clear from the high number of ‘repost’ articles coming from the Missoula Current.

Still, the site never really had a huge change in traffic, and we know this from our ranking posts, which I’ve been putting up every 3 months for the past 3 years:

- June 2017: #331,000

- Sept 2017: #369,000

- March 2018: #346,000

So just 3 months ago, Last Best News was the 346,000th most popular website in the US.

And now they’re shutting down.

A more appropriate term is quitting.

The site is giving up.

For Kemmick and Crisp, it always was about profits.

Anyone who writes about politics in Montana knows this just isn’t the road to take.

I don’t get up most mornings and read the news and the write about it on this site because of profits.

I do it because I’m passionate about it.

You can gauge your passions quite easily – what do you do first thing in the morning when you don’t have anything else to do?

Some people go fishing, or watch TV, or fix up their yard. Some of us write about politics and history.

We do this because we’re passionate, and passionately hopeful that our efforts might bring about change.

Last Best News didn’t see their efforts producing the kind of change they wanted. The site never made a lot of money, despite their fundraisers and their local area advertising.

While it’s true that Kemmick and Crisp could continue to write each day, they’ve simply chosen not to.

Giving up.

Every writer on the sites I listed wants to give up. Most of the time it seems like what we’re doing is pointless and produces nothing.

It’s frustrating, but for some reason…we continue.

It’s the passion.

The last chapter of my sixth volume of Montana history was titled “Selling the Papers, Selling the Public.

I’d like to leave you with a few excerpts from that, as I feel history is repeating itself a bit:

From 1906 to 1920, Montanans enjoyed the choice of 225 different newspapers. What happened was a bust in farming in eastern Montana, followed by the rise of radio and then television after. “The published word, so essential in the political wars of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,” historian Rex Myers writes, “diminished in direct proportion to the spread of electricity in Montana and the media that used it.”

By 1950 there were just over 100 newspapers in Montana. By 1953 there were more than 40 radio broadcasters and receivers. More than 125 different newspapers had disappeared over the 30 years that Anaconda’s “gray blanket” of press ownership had descended. Historian Richard Reutten makes it clear that changes were felt significantly by 1934 in the editorial bent of the Montana newspapers. They “showed less concern with state elections and used less poison on editorial pages,” he notes. What’s more, “the vulgar commentary of company editors was slowly replaced by innocuous platitudes from anonymous figureheads.” Instead of editorials championing one issue while decrying another, “’paid’ advertisements, lobbying, and ubiquitous public relations officers served the same purpose more subtly.” It was clear to many that “Anaconda papers became monuments to indifference.”

“Silence is copper-plated,” locals said of their “copper collar,” the Company control of the press. It got worse as the years wore on, and by the 1950s despair reigned in news offices and the stories they spit out. For it was their omission of important news that was the most troubling. Even the Economist in London pointed out how bad the reporting was in Montana when it did a 1957 story called “Anaconda Country” in which it said the company’s policy of omitting the news stories it didn’t like caused the state’s newspaper readers to become “worse informed about their own affairs than the inhabitants of almost any other state.”

By the end of the turbulent 1920s in Montana, just “150 weeklies and dailies still published.” It wasn’t always like that. “Montana had witnessed six decades of open journalism in the most intense frontier style,” Myers writes of the time before the Gray Blanket descended. In the 1920s the changes were gradual, and not easily noticed until it was too late. “’Name’ editors and ‘town’ newspapers ceased to exist,” Myers writes. “Smaller papers simply folded; larger journals became business, not personal, ventures.”

By 1950 there were just over 100 newspapers in Montana. By 1953 there were more than 40 radio broadcasters and receivers. By 1984 there were eleven daily newspapers in Montana and fifty-one weeklies. In the state as a whole in 1984, there were just 90 newspapers, a far cry from the 225 that had existed in the state just 65 years before. Today Montana has 70 newspapers, maybe less.