It started when both the Yellow and Yangtze flooded their banks. Every single province was flooded, with not one area spared. The “Cannon of Yao” has Emperor Yao describing the flood as “boiling water…pouring forth destruction. Boundless and overwhelming, it overtops hills and mountains.”

It could do with the growing sense of China’s place in the world, and their efforts over the centuries to keep the barbarians out while keeping those special people of Shangdi in. Long before the Yellow Emperor defeated Yandi on the fields of Banquan, the Shennong people that would become the Han Chinese were trying to cement their dominance. A large part of that dominance came from their identification of themselves as people living in a certain area, and leaving that area would shatter that identity. It was simply not something that could be done.

So the people stayed, and went to their islands of high ground as the twin rivers rushed by them on either side, their myriad offshoots and tributaries mixing together in a roiling cauldron of water that would grab hold of anything that touched it, washing it into a murky and horrible death.

Society understandably fell apart. Whatever commerce and marketplaces would have ceased, bartering would have become a life or death endeavor, and self-preservation was a trait that took hold in even the most honorable and loving of individuals. It was every man for himself, and often families were torn apart as the rivers had their way with them, and their sense of honor.

Images of families abandoning children while rushing to higher ground, rulers standing atop balconies as peasants cried for their lives below, and children being flung from backs to lessen the load in the mad dash for survival that comes when death is close on your heels.

There would have been heroic acts as well. Mothers clutching their children tightly as everything around them washed away, fathers tossing children to awaiting arms as the flood waters took them, and rulers spending all that they’d made in futile efforts to stop the water.

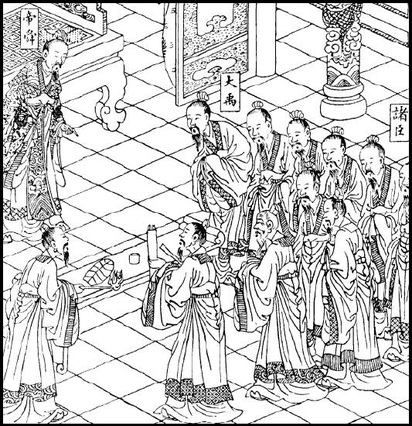

Yao tried everything and turned to everyone. He was a desperate man. Expert advice was sought, and he found it with the Four Mountains. Who or what they were is anyone’s guess, but it’s likely they were advisors, possibly high-ranking and trusted bureaucrats that oversaw an administratively-divided empire. Of course they could have been actual mountains that he rode out and consulted, shouting up to their high peaks in expectation of enlightenment. Perhaps it was a combination of both, but either way, Yao didn’t like the answers he received, and that was to put Yu in charge of flood control.

Great Yu

Legend has it that Yu was never home because of his work and that he’d been married but four days before heading off at the behest of the new emperor Shun. For the next thirteen years he was at work, although he did pass by his home on occasion. Once he heard his wife giving birth. The next time he heard his son call out to him. The final time his son was ten years old and came to the door, asking why Yu wouldn’t stop and stay for awhile. Yu explained that he couldn’t, for while he and his mother had a home, countless others did not and would never again unless he acted – no one else would

One would like to think Yu’s son stood there that day and understood, but it’s hard to see how. The floods had to be stopped however, and both Shun and Yu sought every way imaginable to do that. They key lay in asking heaven for help.

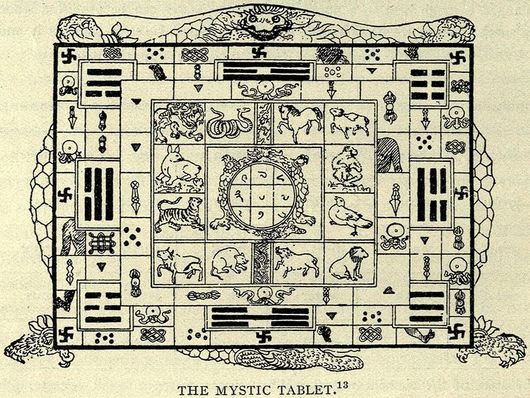

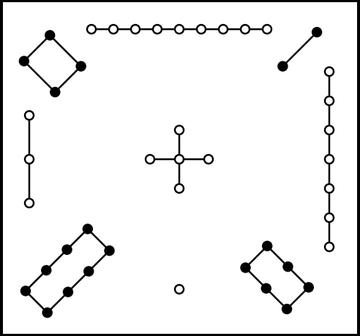

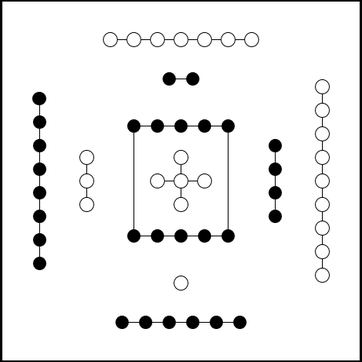

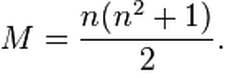

Legend has it that Yao was sacrificing to the gods like crazy during this time, and most of the people were as well. During one particularly large ceremony on the Luo River a large turtle emerged from the river with the Lo Shu pattern on its shell. This is what it looked like:

The Lo Shu Square and Yellow River Map

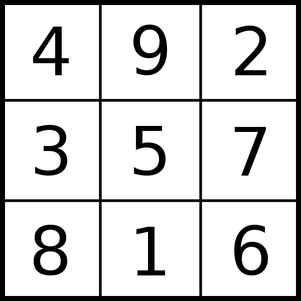

This concept of qi really didn’t get going in China until philosophers like Mozi and Mencius began talking about it around 500 BC, but as with most of the ideas we’ve discussed, it probably has its roots in a much earlier time. These two maps would be described in mathematics as “magic squares.” What that means is that there are distinct numbers arranged in a grid which has an equal number of rows and columns. All of those numbers add up together to the same final number. The formula would look like this:

Go ahead, take a moment and do some addition. Is there any way you can add a straight line of numbers without ’15’ coming up? It might seem like a real simple concept, but it was revolutionary and it allowed Yu to do what both his father and an emperor had been unable to, and that was stop the flooding.

What’s important is that these ancient Chinese thinkers were able to take this Yellow River Map, Lo Shu Square, and the eight trigrams of the I Ching to come up with a unique solution. It meant that instead of trying to stop the waters, they had to be allowed to flow. It meant instead of using dams and dikes, they’d have to use drains and ditches. It meant that instead of trying to control nature, man had to work with it.

These were revolutionary ideas, and Yu wasted no time in implementing them. Legend has it that he found help making these ditches and drains through large swaths of land with a channel-digging dragon and a giant mud-hauling tortoise. Another story has Yu working along the Min River when a whirlpool develops and begins to suck in his boat. From up above a Yellow Dragon swoops down and rescues Yu’s boat. It was such a task that the creature had to thrash about in the river, which created channels and stopped the flooding there.

These creatures were surely invaluable in the task, but it’s far more likely that vast workforces were assembled to complete the huge construction project. They weren’t really constructing, though, but deconstructing.

This was the start of large-scale and widespread irrigation, the likes of which the world probably didn’t see again until modern times. It’s likely the ancient Egyptians were doing much the same at an earlier date with the Nile, but in China it was taken to a whole new level as tens of thousands of people set to work changing the earth around them, many of them slaves.

The rise of the administrative bureaucracy was a necessity in mobilizing the workforces needed. Dividing the country into easy-to-administer regions was critical for completing the tasks. And organizing the calendar and standardizing the weights and measures was essential for timing movements and tasks so that disparate groups in far-flung places could do the same thing at once. It was efficiency on a monumental scale, and cooperation without limit. Humanity rarely has such fine hours.

Yu ruled China for forty-five years before succumbing to an illness at the age of about 100. Like many rulers that came and went in China’s history, he was on a grand tour of his kingdom, this time hunting in the eastern provinces near today’s Shaoxing. Whatever afflicted him – perhaps nothing more than old age – finally brought him down at Kuaiji Mountain. A mausoleum grew up for him in that area during China’s Southern and Northern Dynasties period around 500 AD.

Check out more in the Goodreads East Asian History Group and Buy From Heaven to Earth...on sale now!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed