The Jongurian Mission - A Free Epic Fantasy Novel

In the West, a fragile peace has held the bickering provinces of Adjuria together for the past twenty years. In the East, the Empire of Jonguria has been bound together for generations by force.

But now both countries are losing their grip. Will an Adjurian Royal Council offer up a solution, or will politics prevail? Can two ancient enemies bind their wounds, or is their hope for reconciliation, the Jongurian Mission, doomed from the start?

Join a motley group of war veterans tasked with opening up a reclusive country. But when their mission of peace suddenly turns deadly, all bets are off, and the Jongurian Mission takes on a whole new meaning: survival.

The Jongurian Mission sets you on a dazzling journey through mesmerizing lands filled with unforgettable characters that will thrill fantasy lovers young and old alike. A truly epic read that transcends the fantasy eBook genre!

Amazon Verified Reviews

“…making a film out of this novel would only make sense.” ★★★★★

The world of the Jongurian Mission reminded me of Game of Thrones… ★★★★★

…the author establishes a narrative that the reader won't be able to put down. ★★★★

With vivid descriptions and tight character development, Strandberg takes you on the ultimate adventure. ★★★★

I can't wait to read the rest of the books in the series. ★★★★★

…I absolutely loved it all and found myself wishing the book did not end when it did. ★★★★★

…if a world of medieval royalty is your thing, you should check out the first installment of The Jongurian Trilogy. ★★★

Download The Jongurian Mission for Free today!

But now both countries are losing their grip. Will an Adjurian Royal Council offer up a solution, or will politics prevail? Can two ancient enemies bind their wounds, or is their hope for reconciliation, the Jongurian Mission, doomed from the start?

Join a motley group of war veterans tasked with opening up a reclusive country. But when their mission of peace suddenly turns deadly, all bets are off, and the Jongurian Mission takes on a whole new meaning: survival.

The Jongurian Mission sets you on a dazzling journey through mesmerizing lands filled with unforgettable characters that will thrill fantasy lovers young and old alike. A truly epic read that transcends the fantasy eBook genre!

Amazon Verified Reviews

“…making a film out of this novel would only make sense.” ★★★★★

The world of the Jongurian Mission reminded me of Game of Thrones… ★★★★★

…the author establishes a narrative that the reader won't be able to put down. ★★★★

With vivid descriptions and tight character development, Strandberg takes you on the ultimate adventure. ★★★★

I can't wait to read the rest of the books in the series. ★★★★★

…I absolutely loved it all and found myself wishing the book did not end when it did. ★★★★★

…if a world of medieval royalty is your thing, you should check out the first installment of The Jongurian Trilogy. ★★★

Download The Jongurian Mission for Free today!

The Jongurian Mission

An Epic Fantasy Novel Set in a Medieval and Ancient East Asian World

|

Download Now for Your Kindle

|

Download Now for Your iPad/Nook/Sony

|

Download Now with a PDF

| ||||||||||||||||||

In the West, a fragile peace has held the bickering provinces of Adjuria together for the past twenty years. In the East, the Empire of Jonguria has been bound together for generations by force.

But now both countries are losing their grip. Will an Adjurian Royal Council offer up a solution, or will politics prevail? Can two ancient enemies bind their wounds, or is their hope for reconciliation, the Jongurian Mission, doomed from the start?

Join a motley group of war veterans tasked with opening up a reclusive country. But when their mission of peace suddenly turns deadly, all bets are off, and the Jongurian Mission takes on a whole new meaning: survival.

The Jongurian Mission sets you on a dazzling journey through mesmerizing lands filled with unforgettable characters that will thrill fantasy lovers young and old alike. A truly epic read that transcends the fantasy eBook genre!

But now both countries are losing their grip. Will an Adjurian Royal Council offer up a solution, or will politics prevail? Can two ancient enemies bind their wounds, or is their hope for reconciliation, the Jongurian Mission, doomed from the start?

Join a motley group of war veterans tasked with opening up a reclusive country. But when their mission of peace suddenly turns deadly, all bets are off, and the Jongurian Mission takes on a whole new meaning: survival.

The Jongurian Mission sets you on a dazzling journey through mesmerizing lands filled with unforgettable characters that will thrill fantasy lovers young and old alike. A truly epic read that transcends the fantasy eBook genre!

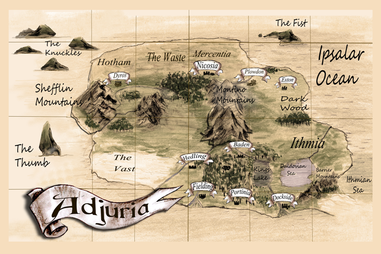

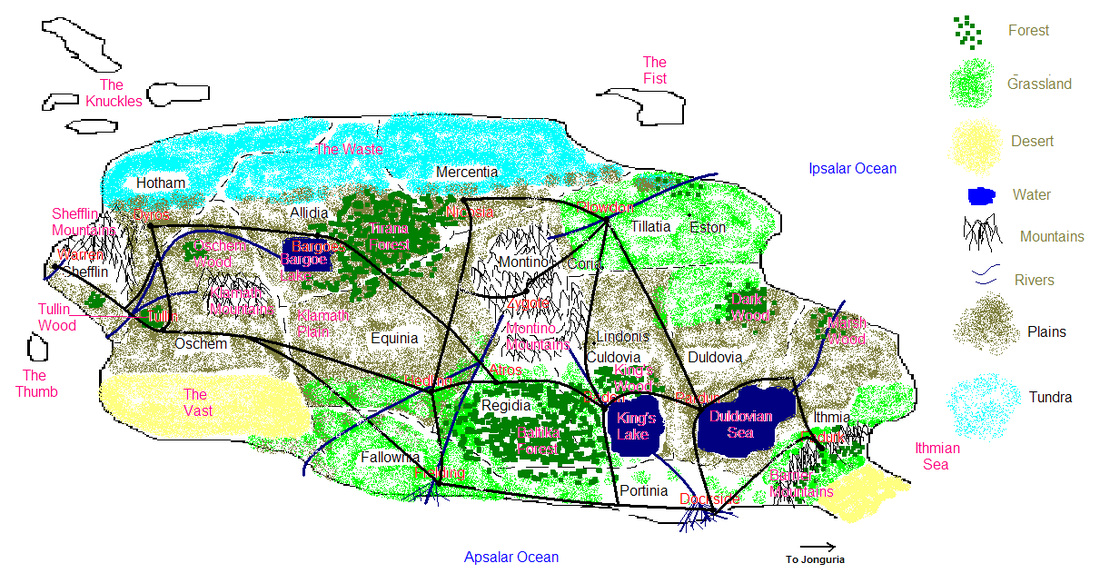

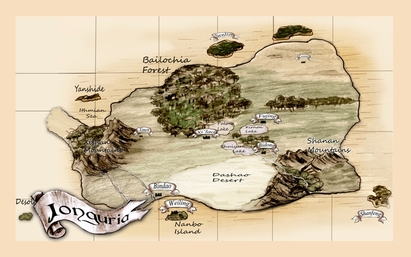

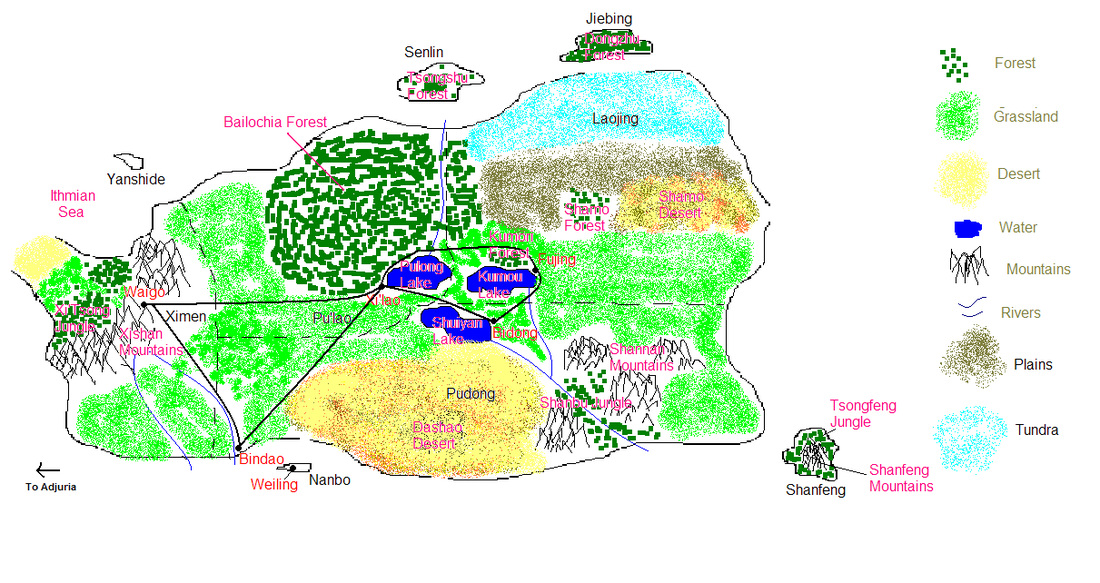

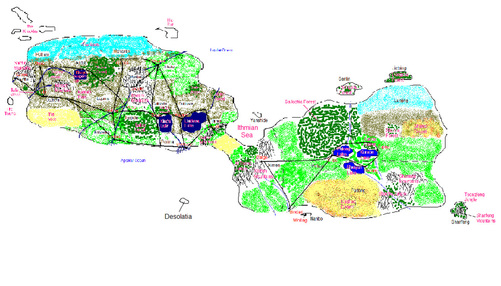

The Jongurian Trilogy Maps

The maps directly below appear in the three books that make up the Jongurian Trilogy. The maps below those were the maps I made using MS Paint when I first came up with the idea for the novels. I actually made the maps before I wrote anything. I thought it was important to have a detailed fantasy map so I could make a detailed fantasy world.

I'm including the maps on this site because they give more detail than the better-looking maps. You'll see the different provincial lines, rivers, roads, and a lot more names. I'm also including a map of both continents, or the whole fantasy world. It's called Pelios, and you can see it below.

I'm including the maps on this site because they give more detail than the better-looking maps. You'll see the different provincial lines, rivers, roads, and a lot more names. I'm also including a map of both continents, or the whole fantasy world. It's called Pelios, and you can see it below.

Excerpt from The Jongurian Mission

Introduction

The wind and waves threatened to overturn the small boat for what seemed the hundredth time. Even in the dark black clouds could be seen overhead, their billowy forms swelling large and ominously. The nearly full moon was completely blocked out by their presence, and if it wasn’t for the continuous lightning flashes the men in the boat wouldn’t have been able to see at all. As it was, the lightning cast the island they were rowing to in an eerie silhouette, and with each new flash they could see that their efforts at the oars were pulling them closer to their goal.

Leisu Tsao sat on the prow of the boat and looked ahead. He didn’t like traveling on water, but if his master bid him, he obliged willingly and without complaint. The voyage here had been anything but uneventful. What should have taken just a few days stretched into more than a week when this storm bore down on them two days into their journey. The seas were usually unmerciful this time of year, but to Leisu it seemed that this storm had a particular vengeance. Perhaps it knew of their objective and disagreed, he had pondered several days before while watching the dark clouds loom over the horizon and block out the sun. After all, if their goal succeeded the balance of nature would irrevocably be upset; their plan would embroil two continents of men, and men had a way of destroying everything around them when they were troubled.

“Pull,” the man directly behind Leisu yelled to the four oarsmen in the boat.

Leisu smiled. Ko Qian was as dutiful as ever, even on this unwanted mission, and in such horrid weather.

“Pull, I said,” Ko yelled again, louder this time.

It seemed to Leisu that the prodding of the men was working; they were getting closer to the shore. What would they find there? Leisu had been skeptical of his master’s plan at first, doubting if the man they were looking for would even still be alive after this long. It had been more than five years now since he’d been exiled to this desolate island that had barely enough to survive on. While numerous species of plants somehow managed to thrive here, none were edible. Whatever animals called this place home were nothing more than small rodents. A man could live on those for some time, but five years? Leisu doubted that very much. No, when they were done searching the island, probably late on the morrow judging by how terrible the weather was, he expected all they would have found was a ragged skeleton with a few tattered remnants of clothing still covering the sun-bleached bones. While his master had no doubts that the man known as the ‘False King’ in the West was still alive and well and just waiting for an opportunity to get off this rock, Leisu wasn’t so sure.

Grandon Fray had gambled everything during the final years of the East-West War that had embroiled Adjuria and Jonguria. Frustrated as much by the ten-year stalemate as the rest of his countrymen, and with no end to the war in sight, Grandon had decided to do something about it, whereas the other nobles merely sat back and waited for something to happen. First he had convinced his king that a grand offensive against the Jongurians was needed in the most unlikely of places: the Isthmus. It seemed farfetched at the time, and was laughable now, but Leisu had come to realize that it was necessary for the man’s plan. When the offensive failed, as it was bound to do, he had done the unthinkable: he killed a king, or at least had the job done for him. Having removed the only obstacle that he saw for peace, Grandon led the rest of the Adjurian nobles in forming a council to govern the country, much to the frustration and useless protests of the rightful young heir to Adjuria and his mother. From there he managed to negotiate an end to the war with Jonguria, setting the stage for a peace agreement. Peace came, rather too quickly Leisu thought, and the Adjurian forces began withdrew from Jonguria.

While Jonguria descended into chaos following the war, Adjuria was able to keep itself together. Grandon cemented his role as the leading noble on the royal council and then managed to have himself named king. He ruled for a few years, but his policies were disastrous and drove the country apart. Who knows, Leisu thought as he got closer to the island, maybe that was all a part of his plan too.

It wasn’t long before some of the other provinces had their fill of Grandon Fray and decided that a boy for a king couldn’t be any worse than this usurper. A brief Civil War broke out, Grandon’s forces were defeated, and the rightful king was put back on the throne. For all of his troubles at ending the war and bringing peace to his country Grandon was exiled to the rock that would forevermore be called Desolatia Island.

Several more bolts of lightning lit up the night sky. The boat was close now, just a few minutes away from the shore. Perhaps it’d be better if Grandon was dead, Leisu thought to himself as the boat neared the rocky beach. The man seemed to bring turmoil to whatever he undertook, and there was more than enough of that in Jonguria at the moment. Did his master really think that more would allow him to increase his control? It wasn’t the first time Leisu thought it was odd that his master, a man who would not tolerate failure, was seeking the aid of a man whose failure had divided a nation against itself and ended in his own downfall. But then Jonguria was already divided against itself, Leisu thought. There were those that supported the emperor, whose numbers seemed to lessen everyday, and those that supported the rebels, whose numbers increased. His master was the leader of the rebels in the southwest, and if his current plans were carried out, he’d soon be the rebel leader of the entire country. Not for the first time since setting out did Leisu again wonder how Grandon Fray could possibly help bring that about.

A few large waves pushed the boat the last few feet forward and they could feel the wooden hull scrape against the rocky shore. The rowers jumped out and pushed the boat further up the beach to a more secure resting place, and then Ko and Leisu jumped out into the white surf. Leisu looked over at Ko and nodded.

“Get out the supplies and find a dry place to put up the tent,” Ko yelled.

Two of the oarsmen jumped back into the boat and began to throw down large bags to the other two, who then threw them further up onto the dry beach. Leisu walked forward to observe the land. From what he could see between lighting flashes the land looked like it could support a man indefinitely. But he knew better. The lush green foliage was useless to men and the rocky cliffs that seemed to rise straight up hundreds of feet from the island’s center were a haven for poisonous snakes, spiders, and other vile creatures. Five years, Leisu thought once again. There could be no way.

A large flash of lighting lit up the sky and the immediate thunder behind it caused him to jump. He felt foolish. What was there to be scared of? This island was as desolate as its name implied. Another flash came and he thought that he saw something ahead of him. He narrowed his eyes into the darkness. It was not until the sky was again lit up again, however, that his suspicions were confirmed: there was someone, or something, moving toward him. He called back at Ko, who in turn yelled at the oarsmen. All gathered behind Leisu, their daggers drawn. Another flash of light came and they could all see a man walking toward them. Could it really be? Leisu thought.

Ko called for one of the men to light a lantern. Its faint glow illuminated a small circle around them, but it was the lighting that really lit up the land. Another flash came and showed the man no more than fifty feet away. A minute later they could hear the unmistakable sound of footfalls scraping sand and rock together. A man stepped into their small arc of light. He had long grey hair going white at the temples with a matching beard that filled his entire face and crowded out the rest of his features. He was well-tanned and frail, his ragged clothing tattered and torn and hanging off him like a sail. He was above-average height for an Adjurian, and stood a head taller than any of the Jongurians, even Leisu, who prided himself on his imposing height.

“I’ve been expecting you,” the man said as he entered the light. His voice was strong and commanding, even if his appearance was not. Leisu immediately sensed the power of the man, and respected him for it. Somehow, against all odds, he’d survived where any lesser man would’ve died.

“Oh?” Leisu replied.

“Yes, I’ve been watching your progress for more than a day now,” the man said.

“Grandon Fray,” Leisu stated more than asked, and the man gave a slight nod.

“Were you expecting someone else?” he asked mockingly.

Usually Leisu wouldn’t have allowed that tone with anyone, but then he had to remember that he was in the presence of a king; even one who had had his predecessor killed to steal the throne, started a Civil War, and then been banished from his country. Men like that were used to taking whatever tone they wanted with whomever they wanted. In their own eyes all were beneath them.

“No, I think not,” Leisu replied to Grandon’s question.

“You’re Jongurian,” he said looking them over. “I expected that my own countrymen would be the ones to free me from my prison,” he lifted his arms to indicate the land around him, “but I’ll not pass up any chance to get off this rock.”

“Good to hear,” Leisu nodded, “we’ve come a long way to find you.”

“May I ask why?”

“Perhaps we should get off this beach first,” Leisu suggested.

“I’ve walked this beach for five years now,” Grandon replied, “it won’t kill you to stand upon it for a few minutes more.”

Leisu gave the man a long look. Five years of exile had done nothing to temper his manners. He still acted much the king, but then Leisu figured that he was still a king: of all of the barren majesty this landscape could produce. He held his temper in check and explained to the reason for their presence.

“We’ve come from Jonguria at the behest of my master Zhou Lao, the man who holds the southwest of the country.” Leisu waited for Grandon to ask a few questions at that declaration, but he remained quiet, so he continued. “He wants to expand his power and influence throughout the rest of the country, and eventually challenge the emperor’s precarious position. He thinks that you might be able to help him with that plan,” Leisu finished, looking at the disheveled Adjurian.

Grandon shook his head. “I don’t see what that has to do with me at all.”

“Your nephew does.”

“My nephew?” Grandon replied questioningly, for the first time taking his eyes off them as he looked into the distance. “Jossen? What could he possibly have in this?”

“Jossen Fray is himself trying to cement his own power in Adjuria. But while we struggle against an emperor and have been for years, your nephew is just beginning his bid to wrest the throne from his king. He believes that an unstable Jonguria will help him achieve that goal, and when my master takes over the country, your nephew will have a strong ally.”

“I see,” Grandon replied, but Leisu doubted that he really did. He himself didn’ see the entire scope of the plan that his master was unveiling, and he assumed that he never would. Many things would remain a mystery to him as these great events unfolded, and Leisu would be remembered in his nation’s history for helping to bring them about. This night on Desolatia Island’s stormy beach was just one of many that he’d leave his mark on.

“Well,” Leisu replied after a few moments of silence. “Would you like to come with us or stay on your island? The choice is yours.”

Grandon looked up at them for a few moments, and then without speaking walked past them and climbed into the boat. Leisu smiled. It had begun.

ONE

“Holy hell! Damn it anyway!”

A string of curses were let loose over the rocky field as a young boy stooped down to his toils.

At above-average height, with short-cropped brown hair and a slight build, though well-muscled from countless hours of exertion in the outdoors, Bryn Fellows could at the same instant strike both an imposing figure, but also one of quiet composure. He was still quite young, only fourteen now, but a lifetime of struggling against both the elements thrown at him by nature and those by men’s demands had given him an outlook and wisdom beyond his years. Still, he was young, and therefore exhibited many of the characteristics and traits common to all young men: quick-to-actions not thought through, disdain for authority, and a sense that the world held no knowledge which his mind did not already possess.

“For crying out loud!” Bryn yelled.

For the third day in a row now Bryn had been slaving away in this rocky, stone-infested field under a blazing sun. The field had lain unused for as long as Bryn could remember, and judging from the amount of three- and four-hand stones lying half-buried, it’d always benn that way. It therefore came as some surprise when Bryn’s uncle Trun had insisted that the field be cleared and made ready for that season’s planting, as if there wasn’t enough work to do around the farm as it was.

Deep down Bryn knew it was necessary. Now that the country was finding its balance again following the turmoil of years past, grain prices were beginning to fall. Trun had been forced to sell-off two pigs and a prized milk cow already this spring, and unless things improved in the grain market, which seemed unlikely, more selling-off of the livestock would have to take place before winter set in. That’s why the cursing stayed in the fields and ended when supper was served each night. Bryn knew if his uncle’s leg was what it used to be he’d be out here as well, sharing in the thankless job now confronting Bryn.

“Damn ye,” Bryn cursed at a stone twice his width as he dropped it beside the pile of smaller stones he’d already cleared over the past two days. There were still a few hours of daylight left, and by the look of the field, Bryn still had another two or three days of hard, back-breaking labor ahead of him. Then it would be on to easier jobs like mending fences or tending the crops. He surveyed the collection of piled rocks and stones as he pulled a cloth from his pocket and began wiping the sweat from his face. Two wagons full, so far, with the promise of at least one more before he was finished. Some would be used to shore up the house, which could do with some new stones to replace some of the older, peices starting to crumble. The rest would most likely be sold off to neighbors, or taken into town to be traded for goods the farm couldn’t produce. They’d not fetch much, but every little bit was a help these days.

It’s funny, Bryn thought. The country is getting back on an even footing after years of war; you’d think things would be getting better for the common people as well. That just wasn’t the case, however, as things only seemed to be getting worse. Even during the years of Civil War, which Bryn was barely old enough to remember, he didn’t recall them fretting over pennies as they were now. All he heard now when the neighbors sometimes gathered or on the few times a year he went into town, was how life for the common folk had dropped to such lows over the past ten years. Things were never this bad when the previous king was in power, all agreed. Even during the war with Jonguria, prices hadn’t been so low for grain. Some even spoke fondly of how prices had gone up for a time under the rule of the Regidian usurper, Grandon Fray, but those voices were quickly silenced with deathly stares, and sometimes physical blows. All however agreed that things couldn’t get worse, and would surely get better next year. But when next year came, worse was all they got.

With a deep sigh, Bryn moved back out into the field and selected another large stone and began half-hauling, half-pushing and dragging it toward the pile with the rest.

“Whoa there!” came a shout from some distance down the road behind Bryn.

He dropped the stone to the ground and turned to look, shielding his eyes as he did so. A lone rider approached, nothing more than a black silhouette in the late afternoon sun. Bryn squinted as best he could to make out more as the rider approached.

“Ho there,” the man said to his horse, pulling on the reins. The horse came to an easy stop, flicking its tail as the man sat looking at Bryn. “My, my lad, you’ve grown since I last laid eyes on you.”

The voice was familiar, but it couldn’t be, Bryn thought to himself. He continued to squint, raising another hand to his forehead.

“Why, don’t you recognize me boy? Has your brain become just as thick as those stones I see you hauling there?”

“Uncle Halam?” Bryn asked in a low, questioning voice. “Is that you?”

“Why, not unless your uncle’s somehow found himself another brother since I’ve last been here.”

“Uncle Halam, it is you!” Bryn shouted as he ran toward the road. He wended his way through the wooden fence as Halam dismounted, then embraced each other on the road. Bryn looked up into his uncle’s face. Yes, it was Halam. Taller than Bryn by a hand, Halam was also a bit wider around the waist, no doubt from the amount of time he sat at his desk, papers strewn before him. His arms were still thick from years in the field with his brother growing up, but he lacked the sun-baked lines which his brother possessed from doing that work still. His short brown hair, balding on top, with the finely-trimmed beard of the same color covering his face, was just as Bryn remembered, although now going grey around the chin and sides. His lips were parted in a wide smile as he looked down on Bryn.

“Good to see you, my boy, it’s been far too long now.”

“Why, Uncle Halam, what are you doing in Eston?” Bryn asked. “I thought you were working for the province in Plowdon and didn’t have the time to come this far east.”

“Why, I can always make time, which I’ve not been doing enough of lately. Truth is, I’ve got something important I want to talk my brother about. Is he about?”

“Yes, of course, he’s over by the house, probably working in the garden.”

“Well, why don’t you call ‘er a day with them damned stones and come with me then?” Halam said with a smile.

“That’s the best idea I’ve heard all day,” Bryn happily replied.

* * * * *

The endless fields rolled around them as they made their way down the road. It was quite a surprise to see Halam, Bryn thought as the two rode on. The last time his uncle visited must have been three or four years ago by now. Halam had spent most of his life in the capital city of Plowdon, but he’d grown up just like Bryn right here on the small family farm not far from Eston. He’d undertaken the same drudgery in the fields day-in and day-out that Bryn now knew so well, and he’d risen above it all to something better, more dignified, official.

Following the Civil War, Halam was made a provincial trade representative, and had spent years traveling around the province, stopping in all the large towns and small villages to appraise the grain output. His tabulations and figures were then be submitted to the head trading office in Tillatia’s capital city of Plowdon, where prices would be set based on the market's demand.

It’d been an easy job, good for a man still young in years who was not ready to settle down to a job in the capital or return to the fields from which he came and start a family, as so many had done after those turbulent years of war. Halam had done the job well and was always warmly accepted into each area of the province he traveled to. It wasn’t long before his popularity with the people caught the attention of the senior officials in the trade office, who quickly appointed Halam to the desk job he’d done so well to avoid for so long. That’s when the job became difficult, for it was the officials who set the price of grain that the people’s ire was directed toward, and their grumbling curses filled the air of many a small tavern throughout the land.

Halam’s carefree lifestyle and journeying around the province had come to an end with his appointment to the capital, and with it also went his well-honed and muscled physique. Years at a desk late into the evening in front of stacks of grain tallies and shipping receipts and the stress that went with being a despised government official had all taken their toll on the once jovial Halam. He was more withdrawn now and not as quick to make a boast or tell a joke.

The farm where Bryn and Trun lived was a good thirty minute walk from the field Bryn was currently working. Riding on the back of Halam’s horse, however, the time was cut down to a quarter of that. Moving up and down as the hills as the road dictated, the two rode over a final hill and before them stretched the farmstead.

There was a one-room dwelling made of stones much like those Bryn had been hauling out of the field for the past three days. The roof was made from wood thatch and straw and did a good job of keeping both the rain and cold out.

Off to the left side and a bit behind the house was a makeshift barn for the animals, another stone edifice with just three sides and a thatch roof. Straw covered the ground inside, where a milk cow stood chewing hay, lazily watching as the two riders approached.

Right next to the house was a large, well-tended vegetable garden. Cabbages, carrots, beats, turnips, onions, peppers, and tomatoes were pushing their leafy stems out of the soil, welcoming the suns’ spring rays. An entire row was devoted to corn stalks, small this early in the year, but showing promise already.

Stooping down to pick weeds from between the rows of vegetables was a man resembling Halam. Whereas Halam had a sizeable girth around his midsection, however, this man was rail-thin, and possessed none of the muscled arms or legs like those of the rider Bryn sat behind. His skin was well-tanned from countless hours under the sun, and his hands were strong and rough from working the land. He was clean-shaven, with long, grey sideburns stretching the length of his face. Large, bushy grey eyebrows jutted from under his round straw hat.

“Uncle Trun, Uncle Trun,” Bryn called from the road as the horse neared the farm, “look, we have company!”

Trun bent up straight and turned in the direction of the approaching horse. He held a hoe in his left hand and with his right removed his hat to wipe away the sweat on his forehead, revealing a pate nearly bald, with some grey tufts of hair on the back and sides. He squinted into the sun, holding his hand up to get a better look.

“Who’ve you got there, boy? Trun asked. “Old Ned to come and buy those stones, is it now?”

Halam led the horse up to the edge of the garden. “Don’t think I’ll be needing stones any time soon, brother.”

“I’ll be, is that you Halam?” Trun asked, squinting up at the rider in front of Bryn.

Bryn hopped off the back of the horse and rushed over to stand next to his other uncle. “It sure is, Uncle, come all the way from Plowdon to see us, he has, isn’t that right, Uncle Halam?”

“That it is lad, that it is,” Halam chuckled. He’d dismounted his horse and slowly walked over to the two, stopping in front of Trun. “How are you Trun, it’s been awhile.”

“I’d say it’s been near four years at that, Halam,” Trun replied. “What brings you all the way out to Eston? Don’t tell me I’ve missed me taxes for the past year. Or are you missing the olden days of honest work and want to get your hands dirty in the soil. We could certainly use the help.”

“No, nothing like that,” Halam replied, “can’t a man come and see his brother and nephew from time to time?”

“Aye, you’re always welcome to that,” said Trun. “Now what do you say to getting out of this blasted sun and inside where it’s nice and cool? Bryn, tie up your uncle’s horse then fetch us a bucket of water and a flask of milk, now.”

“Yes, sir!” Bryn enthusiastically replied as he ran forward and took hold of the reins from Halam before leading the horse to the side of the house where he tied it up to a post near the water trough before running toward the well.

Trun began to walk toward the house, a noticeable limp in his right leg. He leaned the hoe against the front of the house and ducked his head through the door, Halam following slowly behind.

Inside the furnishings were sparse and the space limited. A small table with four wooden chairs stood in the center of the room, with a cook stove set into the back wall next to the fireplace. Two small straw beds sat parallel to each other on opposite sides of the house. It wasn’t much, but it was home.

Trun limped over to one of the chairs at the table and motioned for Halam to take another. He slowly eased down into it, keeping his right leg stretched out straight as he did so, finally sitting with a loud exhalation of breath and visible relief. He put his hands upon the table and stared straight ahead of him, obviously in pain from the ordeal.

“I see the leg’s still giving you grief,” Halam pointed out, sympathy writ clear on his face as he looked into Trun’s eyes.

“Aye, that it is. Most days I get by well enough. She just gets stiff now and then, especially with the change in seasons upon us. But that’s how it is. Can’t do much to change it now, can I? To think, I made it all those years through the war in Jonguria without a scratch, then get the use of my leg’s taken from me fighting my own countrymen. It just ain’t right, I tell you.”

“No, no that it ain’t,” Halam agreed.

Trun was older than Halam by more than five years. He was the oldest of the three brothers, and had also been the first to join in the fighting against Jonguria thirty years before. Of course they’d all been young and foolish back then. Not having seen the world and then to be suddenly offered the opportunity to not only leave Eston and travel to distant parts of Adjuria, but to actually go as far away as Jonguria, well, that had been something they just couldn’t pass up.

Trun had made it through all ten years of that grueling war, being battered to hell and back again each day along the Baishur River. Halam didn’t know how he’d made it. Stronger men than he had succumbed to the madness of those trenches in the first months, but Trun went the distance. But then Halam figured there were men strong of body, but others strong of mind, and Trun had the latter aplenty. He believed in the cause and had been convinced the Jongurians had made the first move against Adjuria in those first days of hostilities. No one still knew exactly how or why the war happened, but happen it did, and Halam had ended up in it as well.

Stationed well south of Trun, he’d been part of the force tasked with keeping the city of Bindao, well after it had fallen to Adjurian troops, been retaken by Jonguria, and fallen again. Halam well remembered the hell that had been, and tried not to think about it. He did his time, and made it back home, also in one piece, like Trun.

After peace had been restored between the two continents and the Civil War between the provinces broke out, both Halam and Trun had sided with the Culdovian cause. They both agreed that the Regidian usurpers had to be stopped and the rightful heir to the Adjurian throne put back in place. Their military experience wasn’t discounted and both were soon commanding companies at the Battle of Baden. Halam had thought he couldn’t see anything worse than his three years at Bindao, but those three days outside the Adjurian capital proved him wrong. He tried not to think about Baden either, but the images of the battle came to him unbidden in his sleep still. Those memories would never be shaken.

It was there that Trun finally suffered the injury that he’d been so lucky to escape all those years along the Baishur River. Leading a charge into the unprotected flank of the Oschem-led wing of the Regidian army, Trun’s horse had been impaled by an enemy lance. When the beast reared up, Trun was thrown to the ground, whereupon his horse fell over on top of him. It was just bad luck that a rock was under his right knee when the beast fell. The knee was shattered, but ironically the injury probably saved his life. Unable to get up, and with the now dead horse blocking him from the sight of the rallying enemy army, Trun was overlooked as his company was slaughtered in a devastating countercharge. He’d always blamed himself for what happened to his men that day, and probably still does, Halam thought.

“If I was only able to get up and have the men see me,” he always said afterward, “the day would have been different. The Battle of Baden would have been over in two days, not three.”

Halam himself had commanded a company at Baden, but whereas Trun’s had met with devastation, Halam’s had enjoyed triumph. For it was Halam that had rallied the men fleeing from Trun’s company and enabled them to make a stand at a position on the field which proved critical for the next days offensive, an offensive which won the battle for the Culdovian army. While Halam was wreathed in the cheering adulation of royal nobles and common soldiers, Trun had lain in a sick tent listening to a doctor tell him he’d never walk again.

It was for Halam’s rally at Baden that he was given the government post in Tillatia, while Trun had no choice but to head back to the family farm and learn to walk again. There were a lot of men in his position in those days when the country was coming off of two wars. Many were in worse shape than Trun, and he knew it. He wasn’t one to complain, and it was less than a year before he was back in the fields, although much slower and unable to do the same heavy work as before.

Bryn came into the room and jolted the two men from their reveries.

“That sure is a good horse you got there, Uncle Halam,” he said as he put the flask of milk down on the table and headed to the stove to retrieve three cups. “Judging from the eyes and teeth, as well as the sheen of her coat, I’d have to guess she’s right out of the nobles’ stables in Plowdon.”

“Well, you’re right that she comes from the stables in Plowdon, but I sure wouldn’t say there’s anything noble about them,” Halam replied as he grabbed the flask and began pouring the milk into the cups Bryn had set on the table.

“I reckon if we had just one horse like that, Uncle Trun,” Bryn said as he settled himself into the remaining chair at the table, “we’d have no need to do any planting at all this spring. I think a horse like that would bring in more than the price of our grain for an entire season.”

“Nonsense, Bryn,” Trun replied, looking sternly at his nephew, but also letting his gaze fall upon Halam. “Who’s having that kind of money around here these days? You know well enough how poor-off most of the folk around Eston are. Many have been hit harder than us, and have had to sell-off far more livestock than we have just to get by, and barely at that, I might add. I’d count my lucky stars each night, if I were you, and be thankful for what we’ve got right here.”

“Yes sir,” Bryn said meekly, bowing his head at the tough rebuke.

A few moments of silence passed before Trun spoke up. “Well, brother, you say you’ve not come out to run us off our land or to even lend a hand in readying it for the busy season ahead of us. What is it we can do for you now?”

Halam drew in his breath and raised up his shoulders, readying himself for what he was sure would be a tough argument to come. “Truth is, Trun, I’ve come to talk about Bryn and most particularly about his future here in Eston.”

“Have you now,” said Trun, eyeing Halam questioningly. “Truth be-told, his future, and all those of Eston, isn’t looking too bright to me these days, what with the price of grain what it is.”

“Yes, the grain market’s been bad for many years, and all know it,” Halam shot back. “It’s like that all over the country. Fallownia is in the same boat, and the smaller grain producing areas in other provinces are also feeling the pinch.” Halam drew in a deep breath and let it out. “I’ve received word from the royal court in Baden that there’s talk of opening up trade negotiations with Jonguria.”

“Jonguria,” Bryn cried out, “but Uncle Halam, we’ve not sent them grain since before the war!”

“Aye, lad, and there’s lots of talk about changing that.”

Bryn, flustered and confused, tried to argue. “But–”

“But, nothing, Bryn,” Trun shot in. “You know as well as anyone how tough times are these days.” His stony gaze moved from Bryn to Halam. “If Jonguria’s wanting our grain, I say we give it to ‘em, at a higher price than they’d be setting for us in Plowdon.”

Halam looked down at his hands. “That’s the talk in Plowdon, and from what I hear, in Baden as well.” He sighed. “What with shipping it all the way to the treaty port on Nanbo Island, or even overland across the isthmus, that cost has got to be made up for.”

“Aye, and it ain’t cheap to get it here from my fields down to Dockside, neither,” Trun pointed out.

“True,” Halam agreed. “I’d say that you could expect half again what you make now selling it to the provincial officials in Plowdon, if we’re able to come to an agreement with the Jongurians. But remember, we’re just in the planning stages at this point. No royal emissaries have been sent to Jonguria with the proposal, and even the royal court at Baden has yet to come to a firm agreement on the subject. This proposed deal could be months, and possibly even years away. Still,” Halam continued, looking up at the two seated at the table with him, “it is something to hope for.”

“Now, though,” Trun continued after a few moments, “I don’t see what any of this has to do with Bryn. A young boy living in the farmlands on the outskirts of the country ain’t got no impact on trade negotiations with Jonguria.”

“True, true,” Halam conceded, “but I’d like him to.”

“Now what are you meaning with that remark, Halam?” Trun asked, his eyes narrowing in suspicion.

“I mean I’d like Bryn to accompany me to Baden to see how a deal like this would move through the royal court.” Halam’s eyes moved from Trun to Bryn. Bryn’s eyes grew wide with excitement as Halam put his hand on the boy’s shoulder. “I want to give him the opportunity to see his country, to get off this farm and put his mind to something besides fields and stones and livestock for a change.”

“You know the place for a boy Bryn’s age is in the fields, learning the value of a hard day’s work!” Trun shot back.

Bryn rose from his chair and planted both hands firmly on the table. “But, Uncle Trun I–”

“Boy,” Trun said in terse, no-nonsense voice as he laid deathly-serious eyes on his nephew, “this conversation is between me and my brother. It might concern you, but you’ll have no part in it. Now, go out and tend to your nightly chores.”

“But I–”

Trun moved his gaze back upon Bryn, saying more with a look than he possibly could with a lengthy tirade.

“Yes, sir,” Bryn murmured, lowering his head as he shuffled out the door into the twilight of the early evening.

* * * * *

The two men sat without speaking or looking at one another for some time, each slowly drinking their cup of milk while weighing the words they would use to persuade the other. Halam broke the silence first.

“Trun, we’re the only family the boy’s got now, and really, I’ll be the first to admit that I’ve not been much of an uncle for him over his life.”

“That’s for damned sure! You’ve been in Plowdon, or moving around the province. But in all those travels, you never saw fit to stop by and pay us a visit, which you easily could have done more than once every handful of years. The boy looks up to you, Halam, heaven knows why, but he does.”

“Aye, I’ve not been the best uncle, not like you Trun, and my duties in Plowdon have caused me to lose sight of family.”

“Aye,” Trun replied.

“Now Trun, we both know the value of hard work, we’ve both our sweat these fields, and I know full well that you still do.”

“Aye,” Trun said, wiping some caked soil from his clothes. “Just because you’ve got your courtly duties to perform in Culdovia doesn’t mean there’s any task for Bryn to perform. Come harvest time we’ve got the clearing of the fields to do and the preparing for the winter to come. There’s certainly no lack of work on this farm, and I can’t do without an extra set of hands.”

“Listen Trun, the boy is smart; he can’t spend the rest of his life like you, farming.”

“And why not,” Trun answered, his anger obviously rising at the perceived sleight.

“He can go places and be more than just another of the countless farmers in Tillatia. Every time I come back here and see Bryn working he’s nearly always got his head in a book, thinking, studying, and improving his mind. There’s a place for that far from these fields.”

“Aye, and how often has he nearly upturned a whole row of freshly laid seeds with his eyes on a book and not on the work under his feet?”

Halam sighed. “Listen, this is a chance for the boy to get out of Tillatia, to see the world, a world at peace, which is a chance that neither of us ever had, Trun.”

“If the world had been at peace all those years ago, you can rest assured, brother, that I never would have left the farm.”

“Let him come with me, Trun, let him see the country he lives in, the country he’s spent so much time reading about in books. Let him walk its roads and breathe its air. A man needs to see the results of his daily labors. I’m not talking about stealing him from you forever, Trun. All I’m saying’s that I want to take him along for this round of talks in Baden. He’d be home in time to help with the harvest come fall.”

“And a fine use he’d be to me then, his head filled with all manner of courtly intrigue and politics, thoughts a-flutter with the latest gossip about the capital’s rising lords and ladies. He’d not know the back end of a hoe from the front by the time you sent him back from that Culdovian hornet’s nest.”

Halam sighed and shifted in his chair, unhappy with the way the discussion was going. His brother had always been stubborn, and he saw that the task of convincing him was going to prove much more difficult than he’d earlier expected.

* * * * *

After looking after the animals and completing his other chores, Bryn sat down on a large rock set off from the barn to rest and think. He couldn’t understand why his Uncle Halam was so interested in taking him to Baden, or why his Uncle Trun was so intent on having him stay on the farm. Bryn would love to go and see the capital of Culdovia, and all the interesting sights along the way, but it also made him nervous. He’d never been further from the farm than the half-day’s ride to Eston, and he considered that town of about a hundred people large. To travel to Baden, where the people numbered in the thousands, well, he just wasn’t sure he was ready for that. It was not that he hadn’t thought about it before. What boy growing up on a small farm on the edge of Adjuria hadn’t? When Bryn thought about it, however, it simply came down to the fact that he didn’t think he was cut out for the courtly and governmental duties that his Uncle Halam performed. All he’d known his whole life was taking care of animals, plowing fields, and harvesting grain. What use was there for the ability to haul stones, mend fences, and milk cows in the capital?

Bryn saw his Uncle Halam emerge from the house and walk over to the garden, stare down at the vegetables, then walk over to the barn where he leaned up against its stone wall.

“Uncle Halam,” Bryn called out, waving his arm in the air.

Halam looked in the general direction of the shout, but with dark coming on fast he couldn’ make out where Bryn was.

“Over here, Uncle Halam, straight ahead,” Bryn shouted.

Halam squinted as he began walking in Bryn’s direction. Finally, a few paces from him, he spotted Bryn and went to join him.

“Well, my boy, what’re you thinking of the talk you heard between me and my brother just now?” Halam asked as he pulled a worn wooden pipe from his travel-stained coat along with a pouch of tobacco leaves which he began to push into the pipe’s bowl.

“I really don’t know, Uncle Halam,” Bryn began, “it just seems like so much all of a sudden. I mean, I’ve never even been to Plowdon, and to now have the chance to go to Baden, well, it just seems so…”

“Overwhelming?” Halam finished for him.

Bryn smiled. “Yes, overwhelming.”

Halam pulled some matches from his coat, lit one on the side of the rock, then lowered it down to the bowl of the pipe. The tobacco caught fire and glowed orange and red as Halam sucked in the smoke, letting it out quickly until he was satisfied he had the pipe going strong before tossing the match at his feet.

“It’s a bit much for a man of any age who’s never seen the capital of Adjuria, no matter where he’s coming from. I remember the first time I laid eyes on her wide, bustling streets. I was awed and intimidated. All I wanted to do was run to the nearest alley and hide behind a heap of trash, hoping it would all go away. But I threw my shoulders back and held my head high, and walked those streets.” Halam smiled at the recollection, and Bryn could see him looking back into the past, seeing those streets as only a man who has walked them before can see them.

“It wasn’t easy, but it wasn’t too difficult either. After a time I got used to it, as much as a man from Tillatia can, mind you.” Halam looked down at Bryn, tousling his hair. “She’s the largest city in the land, Bryn, but we’ve plenty of smaller cities that you can see on the way that will prepare you for her immensity.”

“Which ones,” Bryn asked, his curiosity overcoming his trepidation at the thought of traveling through these wide swaths of civilization.

“Well, we’d start right here in Tillatia with Plowdon, a sizeable city in itself. From there we’d head down the King’s Road, and pass through Coria on the Tillatia-Culdovian border. From there we’d travel to Lindonis on the eastern edge of the Montino Mountains and just north of the King’s Wood. After that we’d be but a days ride from the capital itself.”

“The King’s Wood and the Montino Mountains!” Bryn said with excitement. “I’ve read about them so many times, and even seen some drawings in Eston, but to actually walk along them, well, that would be something.”

“Aye, lad,” Halam agree. “See, it’s nothing to be afraid of, now. What’s to be scaring you is the prospect of staying on this farm for the rest of your life, and not taking the opportunity to see the land your hard labor’s done so much to support. A man’s got to see the land he lives in, as I’ve been trying to tell my brother for the past hour.” Halam signed and tapped out the bowl of his pipe against the rock. “That’s an easy thing to be forgetting when you’ve already seen so much of your country, and another’s besides.”

Halam looked off into the distance, past the farm and Tillatia, all the way outside of Pelios, as far as Bryn could tell. He waited a few moments before venturing to speak.

“So how did the talk go between you and uncle Trun, anyway? From what I heard, he seemed pretty set on me staying here.”

“Aye, that he is, lad, that he is.” Halam put his pipe back into his coat pocket and rose from the rock. “I’m thinking it’ll be best if we let it rest for the night, give the idea some time to settle in our minds before we press it further. I don’t have to be in Plowdon for another few days, so I can wait here tomorrow, perhaps even help out with those stones,” he said with a smile. “Now lad, I think I’ll be turning in for the night. I see you’ve just the two beds inside now, so I’ll make up something for myself in the barn.”

“Oh no, Uncle Halam, you take my bed and I’ll take the barn, it’s-”

“No lad, I think me and my brother need to spend the evening apart, let our words settle, and start fresh in the morning.”

“Well, if that’s what you want,” Bryn said hesitantly.

“Aye, that’s what I want. Now goodnight lad, and say goodnight to Trun for me as well,” Halam said as he ambled off toward the barn. Bryn sat for awhile longer on the rock, thinking of the King’s Road and all of the sights that lay along its path before he got up and headed back to the house.

He opened the door and stepped inside. The house was warm, the fire of the cook stove spreading its warmth through the small area. Trun was sitting at the table, a cup of tea steaming in front of him. Bryn moved to the stove and poured himself a cup, then sat at the table opposite his uncle.

“Halam is going to sleep in the barn tonight,” Bryn reported to his uncle. “I offered him my bed inside, but he refused.”

“Aye, that doesn’t surprise me,” Trun said. “Figured he’d like the chance to sleep out under the stars, enjoy the quiet of the night, which he rarely experiences in the big city.” Trun sipped his tea and leaned back in his chair. His gaze settled on Bryn as he sucked his lips thoughtfully, measuring his words. “So what are you thinking of these plans your uncle has for you, now, lad?”

“Well, it’s a great opportunity, one most folks around these parts will never have. Seems a shame to pass it up. But I can’t help but think that I’ve never even been to a town larger than Eston. To go all the way to Baden, the largest city in Adjuria, it just seems different from anything I’ve ever thought of before.”

“Aye, it is at that. She’ll take your breath away, she will, and more than likely take all the money from your pockets too, whether you know it or not,” Trun replied with a laugh.

“I mean, Uncle Trun, a part of me would really like to go, but another part wants to stay here and help you with the farm. We’ve got the planting to do soon and the sheep to sheer. Once I get done hauling those stones out of the field we can take them around to the neighbors, and shore up the house and barn with the rest. And just getting that field plowed and ready for planting, whether it’s this year or next, will take some time, and lots of back-breaking work to boot.”

Bryn listed all the other tasks the farm needed as far as he saw it, looking Trun right in the eye in the knowing, responsible fashion of one who has an equal share in the gains and losses of their labor. Trun sat back, nodding his head at Bryn’s recitation, seeming to be in total agreement with the words spilling from the boy’s mouth, while in actuality he was coming to realize the truth of the words his brother had spoken earlier.

Bryn was ready to leave the farm and make his way in the world, and probably should have done so well before now. Listening to his nephew expound upon the necessities lying before them which would take them through to another year, Trun knew that Bryn wouldn’t be here to share in their completion. No, Trun knew that the time had come to let the boy go. If he came back in the fall, so be it, there was plenty of work for a strong young man like him; and if he didn’t, well, it was the world’s gain, and she’d be a better place for it.

* * * * *

The stars were well overhead and the moon shone brightly as Halam sat gazing up at them from the edge of the barn’s open side. He sat astride a saddle resting on a log stump, his pipe resting in his hand. The milk cow and horse were both sleeping peacefully, with the soft glow of a lone lantern issuing forth.

Halam shifted himself and turned his head as he heard a sound from the direction of the house.

“Don’t worry, it’s just me,” Trun said as he limped into the lantern’s light.

Halam jumped up from his seat, gesturing for Trun to take his arm. “Here, let me–”

“No, don’t bother,” Trun cut him off, limping over to a bail of hay set up against one stone wall, “I can manage.” He eased himself down, right-leg outstretched just as he’d done earlier in the evening, and sat down with a noticeable grunt.

“So what do you think of this sight?” Trun asked, gesturing up at the nighttime sky. “Don’t expect you see much of these stars in Plowdon unless you ride out of the city quite a ways.”

“No, no you don’t,” Halam said, sitting down on the saddle once again. He tapped his pipe on his boot, and reached into his coat for his pouch of tobacco. “To tell you the truth, I don’t much think about it anymore. Seems I’m so caught up in work most days that once I get home I’m often to bed before the stars even have a chance to come out. Then by the time I’m up in the morning before the dawn, there’s just enough light out that they’ve already gone to bed for the day themselves.” He filled his bowl and replaced the pouch in the inside pocket of his coat. “It is a nice change to see them again on this fine night, I must say.”

“That it is, that it is.”

The two sat in silence, each staring up at the night sky, thinking their own thoughts, wondering and waiting for what the other had to say. Trun spoke first.

“I’m thinking you’re right in wanting to take Bryn with you,” he said, shifting his gaze from the sky to his brother. “He’s too smart to be wasting anymore time hauling stones and plowing fields in the middle of Tillatia while the world rushes on without him.” He sat and looked back up at the stars.

Halam kept his gaze on his brother for a few moments longer, then looked back up himself. Better to let Trun weigh his words and not interrupt his thoughts, he decided. He puffed away at his pipe, waiting for his brother to speak again.

Finally Trun returned his gaze to the darkness beyond the lantern’s light.

“I’d like you to take him to Baden and do whatever it is you do at these trade negotiations, but I don’t want you to bring him back come fall.”

“But,” Halam began, but he was cut-off by Trun’s outstretched hand.

“No, listen to what I’ve got to say,” he said. He looked up at the stars again for a moment, then returned his gaze to the darkness around them.

“This is no place for a lad as smart as Bryn. I want you to find him a task suitable for a young man of his learning when these talks are through, if not in Baden, then closer to home in Plowdon. Heaven knows he’ll not know the difference between the two anyway.”

“Are you sure about this, Trun, I mean, how will you get along without him?”

“Don’t you be worrying about me now, you hear? I’ll manage just fine without him. Did just that for many years before he came along anyway, and can do so still.”

Halam glanced down at Trun’s right leg outstretched in front of him. He looked out into the darkness and nodded his head.

Both men stared into the darkness of the night. After some time Trun straightened out is left leg and slowly began to rise up from the bail of hay.

“You get some sleep now. I figure you’ll both be wanting to set out early in the morning to get a good start on making Plowdon by the day after tomorrow.” He began to limp back toward the house, leaving Halam to stare after him and wonder about the sudden change of heart.

The wind and waves threatened to overturn the small boat for what seemed the hundredth time. Even in the dark black clouds could be seen overhead, their billowy forms swelling large and ominously. The nearly full moon was completely blocked out by their presence, and if it wasn’t for the continuous lightning flashes the men in the boat wouldn’t have been able to see at all. As it was, the lightning cast the island they were rowing to in an eerie silhouette, and with each new flash they could see that their efforts at the oars were pulling them closer to their goal.

Leisu Tsao sat on the prow of the boat and looked ahead. He didn’t like traveling on water, but if his master bid him, he obliged willingly and without complaint. The voyage here had been anything but uneventful. What should have taken just a few days stretched into more than a week when this storm bore down on them two days into their journey. The seas were usually unmerciful this time of year, but to Leisu it seemed that this storm had a particular vengeance. Perhaps it knew of their objective and disagreed, he had pondered several days before while watching the dark clouds loom over the horizon and block out the sun. After all, if their goal succeeded the balance of nature would irrevocably be upset; their plan would embroil two continents of men, and men had a way of destroying everything around them when they were troubled.

“Pull,” the man directly behind Leisu yelled to the four oarsmen in the boat.

Leisu smiled. Ko Qian was as dutiful as ever, even on this unwanted mission, and in such horrid weather.

“Pull, I said,” Ko yelled again, louder this time.

It seemed to Leisu that the prodding of the men was working; they were getting closer to the shore. What would they find there? Leisu had been skeptical of his master’s plan at first, doubting if the man they were looking for would even still be alive after this long. It had been more than five years now since he’d been exiled to this desolate island that had barely enough to survive on. While numerous species of plants somehow managed to thrive here, none were edible. Whatever animals called this place home were nothing more than small rodents. A man could live on those for some time, but five years? Leisu doubted that very much. No, when they were done searching the island, probably late on the morrow judging by how terrible the weather was, he expected all they would have found was a ragged skeleton with a few tattered remnants of clothing still covering the sun-bleached bones. While his master had no doubts that the man known as the ‘False King’ in the West was still alive and well and just waiting for an opportunity to get off this rock, Leisu wasn’t so sure.

Grandon Fray had gambled everything during the final years of the East-West War that had embroiled Adjuria and Jonguria. Frustrated as much by the ten-year stalemate as the rest of his countrymen, and with no end to the war in sight, Grandon had decided to do something about it, whereas the other nobles merely sat back and waited for something to happen. First he had convinced his king that a grand offensive against the Jongurians was needed in the most unlikely of places: the Isthmus. It seemed farfetched at the time, and was laughable now, but Leisu had come to realize that it was necessary for the man’s plan. When the offensive failed, as it was bound to do, he had done the unthinkable: he killed a king, or at least had the job done for him. Having removed the only obstacle that he saw for peace, Grandon led the rest of the Adjurian nobles in forming a council to govern the country, much to the frustration and useless protests of the rightful young heir to Adjuria and his mother. From there he managed to negotiate an end to the war with Jonguria, setting the stage for a peace agreement. Peace came, rather too quickly Leisu thought, and the Adjurian forces began withdrew from Jonguria.

While Jonguria descended into chaos following the war, Adjuria was able to keep itself together. Grandon cemented his role as the leading noble on the royal council and then managed to have himself named king. He ruled for a few years, but his policies were disastrous and drove the country apart. Who knows, Leisu thought as he got closer to the island, maybe that was all a part of his plan too.

It wasn’t long before some of the other provinces had their fill of Grandon Fray and decided that a boy for a king couldn’t be any worse than this usurper. A brief Civil War broke out, Grandon’s forces were defeated, and the rightful king was put back on the throne. For all of his troubles at ending the war and bringing peace to his country Grandon was exiled to the rock that would forevermore be called Desolatia Island.

Several more bolts of lightning lit up the night sky. The boat was close now, just a few minutes away from the shore. Perhaps it’d be better if Grandon was dead, Leisu thought to himself as the boat neared the rocky beach. The man seemed to bring turmoil to whatever he undertook, and there was more than enough of that in Jonguria at the moment. Did his master really think that more would allow him to increase his control? It wasn’t the first time Leisu thought it was odd that his master, a man who would not tolerate failure, was seeking the aid of a man whose failure had divided a nation against itself and ended in his own downfall. But then Jonguria was already divided against itself, Leisu thought. There were those that supported the emperor, whose numbers seemed to lessen everyday, and those that supported the rebels, whose numbers increased. His master was the leader of the rebels in the southwest, and if his current plans were carried out, he’d soon be the rebel leader of the entire country. Not for the first time since setting out did Leisu again wonder how Grandon Fray could possibly help bring that about.

A few large waves pushed the boat the last few feet forward and they could feel the wooden hull scrape against the rocky shore. The rowers jumped out and pushed the boat further up the beach to a more secure resting place, and then Ko and Leisu jumped out into the white surf. Leisu looked over at Ko and nodded.

“Get out the supplies and find a dry place to put up the tent,” Ko yelled.

Two of the oarsmen jumped back into the boat and began to throw down large bags to the other two, who then threw them further up onto the dry beach. Leisu walked forward to observe the land. From what he could see between lighting flashes the land looked like it could support a man indefinitely. But he knew better. The lush green foliage was useless to men and the rocky cliffs that seemed to rise straight up hundreds of feet from the island’s center were a haven for poisonous snakes, spiders, and other vile creatures. Five years, Leisu thought once again. There could be no way.

A large flash of lighting lit up the sky and the immediate thunder behind it caused him to jump. He felt foolish. What was there to be scared of? This island was as desolate as its name implied. Another flash came and he thought that he saw something ahead of him. He narrowed his eyes into the darkness. It was not until the sky was again lit up again, however, that his suspicions were confirmed: there was someone, or something, moving toward him. He called back at Ko, who in turn yelled at the oarsmen. All gathered behind Leisu, their daggers drawn. Another flash of light came and they could all see a man walking toward them. Could it really be? Leisu thought.

Ko called for one of the men to light a lantern. Its faint glow illuminated a small circle around them, but it was the lighting that really lit up the land. Another flash came and showed the man no more than fifty feet away. A minute later they could hear the unmistakable sound of footfalls scraping sand and rock together. A man stepped into their small arc of light. He had long grey hair going white at the temples with a matching beard that filled his entire face and crowded out the rest of his features. He was well-tanned and frail, his ragged clothing tattered and torn and hanging off him like a sail. He was above-average height for an Adjurian, and stood a head taller than any of the Jongurians, even Leisu, who prided himself on his imposing height.

“I’ve been expecting you,” the man said as he entered the light. His voice was strong and commanding, even if his appearance was not. Leisu immediately sensed the power of the man, and respected him for it. Somehow, against all odds, he’d survived where any lesser man would’ve died.

“Oh?” Leisu replied.

“Yes, I’ve been watching your progress for more than a day now,” the man said.

“Grandon Fray,” Leisu stated more than asked, and the man gave a slight nod.

“Were you expecting someone else?” he asked mockingly.

Usually Leisu wouldn’t have allowed that tone with anyone, but then he had to remember that he was in the presence of a king; even one who had had his predecessor killed to steal the throne, started a Civil War, and then been banished from his country. Men like that were used to taking whatever tone they wanted with whomever they wanted. In their own eyes all were beneath them.

“No, I think not,” Leisu replied to Grandon’s question.

“You’re Jongurian,” he said looking them over. “I expected that my own countrymen would be the ones to free me from my prison,” he lifted his arms to indicate the land around him, “but I’ll not pass up any chance to get off this rock.”

“Good to hear,” Leisu nodded, “we’ve come a long way to find you.”

“May I ask why?”

“Perhaps we should get off this beach first,” Leisu suggested.

“I’ve walked this beach for five years now,” Grandon replied, “it won’t kill you to stand upon it for a few minutes more.”

Leisu gave the man a long look. Five years of exile had done nothing to temper his manners. He still acted much the king, but then Leisu figured that he was still a king: of all of the barren majesty this landscape could produce. He held his temper in check and explained to the reason for their presence.

“We’ve come from Jonguria at the behest of my master Zhou Lao, the man who holds the southwest of the country.” Leisu waited for Grandon to ask a few questions at that declaration, but he remained quiet, so he continued. “He wants to expand his power and influence throughout the rest of the country, and eventually challenge the emperor’s precarious position. He thinks that you might be able to help him with that plan,” Leisu finished, looking at the disheveled Adjurian.

Grandon shook his head. “I don’t see what that has to do with me at all.”

“Your nephew does.”

“My nephew?” Grandon replied questioningly, for the first time taking his eyes off them as he looked into the distance. “Jossen? What could he possibly have in this?”

“Jossen Fray is himself trying to cement his own power in Adjuria. But while we struggle against an emperor and have been for years, your nephew is just beginning his bid to wrest the throne from his king. He believes that an unstable Jonguria will help him achieve that goal, and when my master takes over the country, your nephew will have a strong ally.”

“I see,” Grandon replied, but Leisu doubted that he really did. He himself didn’ see the entire scope of the plan that his master was unveiling, and he assumed that he never would. Many things would remain a mystery to him as these great events unfolded, and Leisu would be remembered in his nation’s history for helping to bring them about. This night on Desolatia Island’s stormy beach was just one of many that he’d leave his mark on.

“Well,” Leisu replied after a few moments of silence. “Would you like to come with us or stay on your island? The choice is yours.”

Grandon looked up at them for a few moments, and then without speaking walked past them and climbed into the boat. Leisu smiled. It had begun.

ONE

“Holy hell! Damn it anyway!”

A string of curses were let loose over the rocky field as a young boy stooped down to his toils.

At above-average height, with short-cropped brown hair and a slight build, though well-muscled from countless hours of exertion in the outdoors, Bryn Fellows could at the same instant strike both an imposing figure, but also one of quiet composure. He was still quite young, only fourteen now, but a lifetime of struggling against both the elements thrown at him by nature and those by men’s demands had given him an outlook and wisdom beyond his years. Still, he was young, and therefore exhibited many of the characteristics and traits common to all young men: quick-to-actions not thought through, disdain for authority, and a sense that the world held no knowledge which his mind did not already possess.

“For crying out loud!” Bryn yelled.

For the third day in a row now Bryn had been slaving away in this rocky, stone-infested field under a blazing sun. The field had lain unused for as long as Bryn could remember, and judging from the amount of three- and four-hand stones lying half-buried, it’d always benn that way. It therefore came as some surprise when Bryn’s uncle Trun had insisted that the field be cleared and made ready for that season’s planting, as if there wasn’t enough work to do around the farm as it was.

Deep down Bryn knew it was necessary. Now that the country was finding its balance again following the turmoil of years past, grain prices were beginning to fall. Trun had been forced to sell-off two pigs and a prized milk cow already this spring, and unless things improved in the grain market, which seemed unlikely, more selling-off of the livestock would have to take place before winter set in. That’s why the cursing stayed in the fields and ended when supper was served each night. Bryn knew if his uncle’s leg was what it used to be he’d be out here as well, sharing in the thankless job now confronting Bryn.

“Damn ye,” Bryn cursed at a stone twice his width as he dropped it beside the pile of smaller stones he’d already cleared over the past two days. There were still a few hours of daylight left, and by the look of the field, Bryn still had another two or three days of hard, back-breaking labor ahead of him. Then it would be on to easier jobs like mending fences or tending the crops. He surveyed the collection of piled rocks and stones as he pulled a cloth from his pocket and began wiping the sweat from his face. Two wagons full, so far, with the promise of at least one more before he was finished. Some would be used to shore up the house, which could do with some new stones to replace some of the older, peices starting to crumble. The rest would most likely be sold off to neighbors, or taken into town to be traded for goods the farm couldn’t produce. They’d not fetch much, but every little bit was a help these days.

It’s funny, Bryn thought. The country is getting back on an even footing after years of war; you’d think things would be getting better for the common people as well. That just wasn’t the case, however, as things only seemed to be getting worse. Even during the years of Civil War, which Bryn was barely old enough to remember, he didn’t recall them fretting over pennies as they were now. All he heard now when the neighbors sometimes gathered or on the few times a year he went into town, was how life for the common folk had dropped to such lows over the past ten years. Things were never this bad when the previous king was in power, all agreed. Even during the war with Jonguria, prices hadn’t been so low for grain. Some even spoke fondly of how prices had gone up for a time under the rule of the Regidian usurper, Grandon Fray, but those voices were quickly silenced with deathly stares, and sometimes physical blows. All however agreed that things couldn’t get worse, and would surely get better next year. But when next year came, worse was all they got.

With a deep sigh, Bryn moved back out into the field and selected another large stone and began half-hauling, half-pushing and dragging it toward the pile with the rest.

“Whoa there!” came a shout from some distance down the road behind Bryn.

He dropped the stone to the ground and turned to look, shielding his eyes as he did so. A lone rider approached, nothing more than a black silhouette in the late afternoon sun. Bryn squinted as best he could to make out more as the rider approached.

“Ho there,” the man said to his horse, pulling on the reins. The horse came to an easy stop, flicking its tail as the man sat looking at Bryn. “My, my lad, you’ve grown since I last laid eyes on you.”

The voice was familiar, but it couldn’t be, Bryn thought to himself. He continued to squint, raising another hand to his forehead.

“Why, don’t you recognize me boy? Has your brain become just as thick as those stones I see you hauling there?”

“Uncle Halam?” Bryn asked in a low, questioning voice. “Is that you?”

“Why, not unless your uncle’s somehow found himself another brother since I’ve last been here.”

“Uncle Halam, it is you!” Bryn shouted as he ran toward the road. He wended his way through the wooden fence as Halam dismounted, then embraced each other on the road. Bryn looked up into his uncle’s face. Yes, it was Halam. Taller than Bryn by a hand, Halam was also a bit wider around the waist, no doubt from the amount of time he sat at his desk, papers strewn before him. His arms were still thick from years in the field with his brother growing up, but he lacked the sun-baked lines which his brother possessed from doing that work still. His short brown hair, balding on top, with the finely-trimmed beard of the same color covering his face, was just as Bryn remembered, although now going grey around the chin and sides. His lips were parted in a wide smile as he looked down on Bryn.

“Good to see you, my boy, it’s been far too long now.”

“Why, Uncle Halam, what are you doing in Eston?” Bryn asked. “I thought you were working for the province in Plowdon and didn’t have the time to come this far east.”

“Why, I can always make time, which I’ve not been doing enough of lately. Truth is, I’ve got something important I want to talk my brother about. Is he about?”

“Yes, of course, he’s over by the house, probably working in the garden.”

“Well, why don’t you call ‘er a day with them damned stones and come with me then?” Halam said with a smile.

“That’s the best idea I’ve heard all day,” Bryn happily replied.

* * * * *

The endless fields rolled around them as they made their way down the road. It was quite a surprise to see Halam, Bryn thought as the two rode on. The last time his uncle visited must have been three or four years ago by now. Halam had spent most of his life in the capital city of Plowdon, but he’d grown up just like Bryn right here on the small family farm not far from Eston. He’d undertaken the same drudgery in the fields day-in and day-out that Bryn now knew so well, and he’d risen above it all to something better, more dignified, official.

Following the Civil War, Halam was made a provincial trade representative, and had spent years traveling around the province, stopping in all the large towns and small villages to appraise the grain output. His tabulations and figures were then be submitted to the head trading office in Tillatia’s capital city of Plowdon, where prices would be set based on the market's demand.

It’d been an easy job, good for a man still young in years who was not ready to settle down to a job in the capital or return to the fields from which he came and start a family, as so many had done after those turbulent years of war. Halam had done the job well and was always warmly accepted into each area of the province he traveled to. It wasn’t long before his popularity with the people caught the attention of the senior officials in the trade office, who quickly appointed Halam to the desk job he’d done so well to avoid for so long. That’s when the job became difficult, for it was the officials who set the price of grain that the people’s ire was directed toward, and their grumbling curses filled the air of many a small tavern throughout the land.

Halam’s carefree lifestyle and journeying around the province had come to an end with his appointment to the capital, and with it also went his well-honed and muscled physique. Years at a desk late into the evening in front of stacks of grain tallies and shipping receipts and the stress that went with being a despised government official had all taken their toll on the once jovial Halam. He was more withdrawn now and not as quick to make a boast or tell a joke.

The farm where Bryn and Trun lived was a good thirty minute walk from the field Bryn was currently working. Riding on the back of Halam’s horse, however, the time was cut down to a quarter of that. Moving up and down as the hills as the road dictated, the two rode over a final hill and before them stretched the farmstead.

There was a one-room dwelling made of stones much like those Bryn had been hauling out of the field for the past three days. The roof was made from wood thatch and straw and did a good job of keeping both the rain and cold out.

Off to the left side and a bit behind the house was a makeshift barn for the animals, another stone edifice with just three sides and a thatch roof. Straw covered the ground inside, where a milk cow stood chewing hay, lazily watching as the two riders approached.

Right next to the house was a large, well-tended vegetable garden. Cabbages, carrots, beats, turnips, onions, peppers, and tomatoes were pushing their leafy stems out of the soil, welcoming the suns’ spring rays. An entire row was devoted to corn stalks, small this early in the year, but showing promise already.